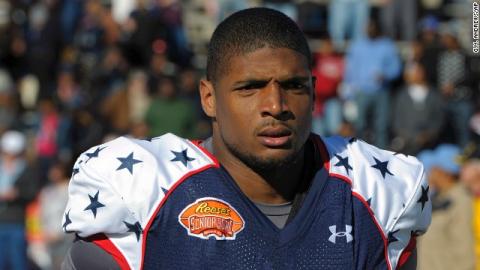

Missouri defensive lineman Michael Sam was the co-winner of the Defensive Player of the Year for the powerhouse Southeastern Conference. While a little undersized for an NFL player at his position, Sam was certainly a decent pro prospect certain to be selected in the upcoming NFL draft. But Sam is no longer just of interest to SEC fans and NFL draft obsessives. On Sunday, Sam came out as gay. If he makes an NFL roster, he would certainly not be the first gay man to play in the NFL, but he would be the first to be out to the public during his playing career. Whether he will get a fair shot to make it as an NFL player, however, is not entirely clear, as multiple NFL decisionmakers have announced their intent to discriminate.

Of course, these anonymous executives and coaches who spoke to Sports Illustrated cloaked their bias in various passive-aggressive evasions. A gay player would "chemically imbalance an NFL locker room and meeting room" said one. "[D]o you really want to be the top of the conversation for everything without ever having played a down in this league?" asked another. It's not that these decision makers are biased, mind you—there are rumors that some of their best friends are gay!—but the prejudices of existing players must be accommodated, and the media attention generated by Sam would just be too much of a distraction.

But let's be clear—whether cynical or sincere, these attempts to pass the buck are functionally and morally indistinguishable from simple bigotry. Both in the sports world and in society as a whole, these kinds of excuses have always been used to justify systematic discrimination. Inevitably, the arguments both make little sense on their own terms and would be indefensible even if they were narrowly right.

Anyone familiar with the breaking of the color line in baseball, for example, will know these feeble tautologies and non-sequiturs. Even in a context in which substantial parts of the country were formally segregated, baseball's elites would rarely defend the exclusion of African-Americans explicitly. The racist commisioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis farcically maintained that there was no policy of discrimination despite decades of lily-white rosters, and the owners followed his lead. As Jules Tygiel explained in his classic Baseball's Great Experiment, "[u]nable to acknowledge discrimination, owners developed a series of rationales defending the necessity of separate competition. Wherever possible, they attempted to shift responsibility to other parties or to blame circumstances beyond their control." Tygeil's description applies precisely to the justifications for discrimination offered by NFL decisionmakers.

As Deadspin's Drew Magary argues, the assertion that Sam is too much of a "distraction" to justify a roster spot is particularly silly. NFL games are not played in private, and extensive media coverage is something teams have to deal with and in some cases will welcome. You create a greater media "distraction" by drafting Andrew Luck rather than Brandon Weedon, and the Super Bowl champion Seahawks will face considerably more "distraction" from the media than the Jacksonville Jaguars will. Good organizations can deal with this if not use it to their advantage. The Brooklyn Dodgers were so distracted by Jackie Robinson's presence that they won six National League pennants in his decade with the team, including in his rookie year. (Robinson's 1953 Dodgers outscored the next best offensive team in the league by nearly 200 runs. But if not for the distraction created by his presence they could have been really good!) The Cleveland Indians, who broke the American League's color line, were so distracted they won the World Series in Larry Doby's first full year with the team and would go on to set the American League record for wins in a season with the first African-American player in the league still patrolling the outfield. If breaking barriers of prejudice is devastating to an organization's chances of winning, history keeps it well hidden.

But even if we assumed for the sake of argument that Sam would be a "distraction" and risk team discord, it's a terrible argument. It's an assumption that makes all discrimination self-justifying. In the 1970s, more than one Supreme Court justice threatened to resign if a woman was appointed to the Court because the breakup of their boy's club would make them uncomfortable. The appropriate response to this is "let me call you a cab so we can get on with appointing someone who's serious about the job," not "women will have to wait so that we don't offend your petty prejudices." The same goes for the NFL. It's the responsibility of players to accept gay teammates, not the responsibility of gay players to remain in the closet or out of the league until all prejudices can be eliminated. That's not how social change can or should work.

Indeed, what particularly strange about the argument that "my team isn't ready for a gay player" is that the people making it don't seem to recognize what it says about their teams. Asserting that you have a coaching staff who would be happy to let homophobic bullies tear the team apart, or a roster full of players to whom petty prejudices are more important than winning, suggests problems that avoiding Michael Sam in the draft sure won't solve. Not only is announcing your intent to discriminate immoral, it shows how little you think of your employees or co-workers. Saying that your team isn't ready for Michael Sam isn't about winning; among other things, it involves calling your team dyed-in-the-wool losers.

Scott Lemieux is an assistant professor of political science at the College of Saint Rose. He contributes to the blogs Lawyers, Guns, and Money and Vox Pop.

Spread the word