“Here is what I would like for you to know,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son, Samori, in Between the World and Me: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage.”

The violence to which Coates refers encompasses slavery, the terror of Jim Crow, and police brutality right up to the present moment. And in his new book, as in his previous work, Coates insists that no amount of “personal responsibility” on the part of African Americans can shield them from it.

This truth was brought home to him by the death of Prince Jones, one of Coates's Howard University classmates, who was killed by a suburban-Maryland police officer in 2000. The officer claimed that he shot Jones in self-defense after Jones tried to run him over with his Jeep. It’s a story that the authorities accepted but that Coates does not.

The crucial thing to understand about Prince Jones is this: In a society that promised to reward talent and effort, he and his family had done more than hold up their side of the bargain. His mother, Mabel Jones, was raised poor but swore that she wasn't "going to live like this" all her life. She made good on the pledge, eventually winning a full scholarship to Louisiana State University en route to a career as a radiologist. Her son, Prince—a Howard graduate, a man of faith—did his part, too. But none of that was enough to protect him.

Reading Coates’s words transported me back to a conversation I had with my father, a lifelong civil-rights activist, in 1992. The topic, you might say, was my Prince Jones—Rodney King, who was savagely beaten by members of the Los Angeles police force. Even though their actions were captured on video, the officers were acquitted.

What was the point of a career learning to craft and apply rules if, just when you needed them, they turned out to be a sham?

I had just graduated from law school, and I told my dad that the case made me doubt my career choice. I had gone to law school thinking that I would do something in the service of black people. But what was the point of a career learning to craft and apply rules if, just when you needed them, they turned out to be a sham?

My dad said something vaguely reassuring, but I was young and hard-headed, and his words just made things worse. So I drew from his own life to prove the pointlessness of struggle.

Back when he was about my age, my dad had been stopped by the L.A. police near the campus of the University of Southern California, where he was a student. They told him they wanted to question him about a robbery. Despite the fact that he had been sitting in a nearby campus library when the robbery took place, they refused his pleas to take the simple step of walking inside to confirm his presence with the librarian at the desk. My dad was outraged by their refusal, and their insistence that he come to the precinct for questioning. But, as he would later write in his memoir, “It was hopeless. They had the guns.”

They took him to a cell, and after he began mouthing off about his rights and the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence (he was studying political science, and I got my hard-headedness from somewhere), the police did what they did to black people—which is to say, whatever they wanted. They held him for days, beat him to the bone, and interrogated him without mercy. (“We're tired of you Chicago niggers coming out here to the coast and robbing and going back to Chicago.”) Eventually, when it became clear he wouldn’t confess to a crime he hadn’t committed, they dumped him on the street outside the precinct with no money and no way to get home.

This had happened to my dad in 1953. If Rodney King, almost 40 years later, could be beat down like this, on camera, and still nothing was done about it, surely my dad had to see that nothing had changed—and that nothing ever would.

What he said to me then, and what he didn’t, surprised me. I expected my dad to point out, as he often did, all that had changed since he was my age. And of course, he would have been right: I lived a life of freedom and opportunity unimaginable to his generation, and I never forgot, or will forget, that his struggle made my world possible.

He said that none of his fights were ones that he thought he would win in his lifetime. Or even mine.

But on this day, my dad answered differently. Maybe his characteristic optimism had been dealt its own blow when Rodney King’s attackers were exonerated. Maybe he sensed that my despair called for deeper wisdom. But whatever the reason, he decided to talk about the permanence of injustice. He said that none of his fights were ones that he thought he would win in his lifetime. Or even mine. He was fighting, he said, “for 10,000 years from tomorrow.” And he turned my story on its head: He said that the fact that the L.A. police were still abusing black people, the fact that I could draw a line from him to Rodney King, was precisely why we had to keep fighting.

The memory of my dad's words, in turn, brings me back to Coates. As a writer and as a father, Coates is clear-eyed about the obstacles arrayed against black people. He warns Samori that “there is no uplifting way” to tell his story, that he comes with “no praise anthems, nor old Negro spirituals.” And yet, he urges his son to keep fighting. “Struggle for the memory of your ancestors,” he writes. “Struggle for wisdom ... Struggle for your grandmother and your grandfather, and for your name.” At another point, he writes, “the struggle is really all I have for you because it is the only portion of the world under your control.”

This exhortation echoes remarks Coates made last fall in an interview with The Root:

It would be absolutely just, like, the highest sort of wrong, a moral betrayal, to retreat to a corner and curl up in a fetal position. Even if I believed there was no hope at all. Resistance, in and of itself—struggle, in and of itself—is rewarding.

It’s very tough to explain that to people. It’s hard to get that across, ’cause I think we feel like, well, if this isn’t gonna get fixed, and we don’t feel like it’s gonna get fixed, what are we struggling for? But for me the question is, well, what is your life about? What are your values? How do you want your life spent? And I want my life spent struggling. This is how I want to live.

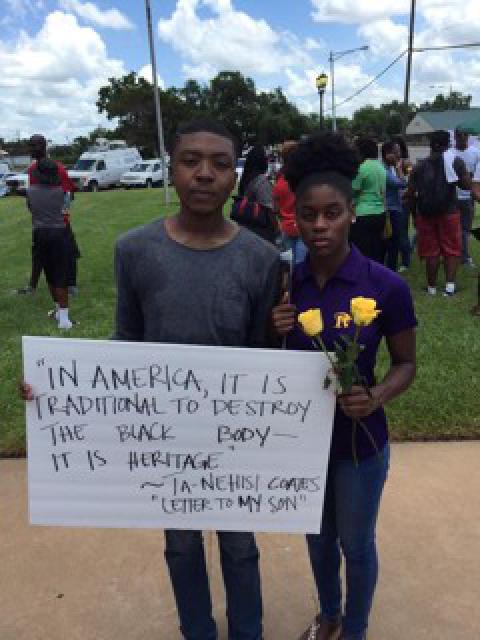

Members of a new generation are making that choice. Recently Coates retweeted a message from a demonstration protesting the death of a black woman, Sandra Bland, in a Texas jail: “@tanehisicoates gave me the language to protest for #SandraBland today in Waller, TX.” Accompanying the tweet was a picture with two young people holding a sign quoting from Between the World and Me.

Spread the word