The criminal justice system has a problem, and its name is forensics. This was the message I heard at the Forensic Science Research Evaluation Workshop held May 26–27 at the AAAS headquarters in Washington, D.C. I spoke about pseudoscience but then listened in dismay at how the many fields in the forensic sciences that I assumed were reliable (DNA, fingerprints, and so on) in fact employ unreliable or untested techniques and show inconsistencies between evaluators of evidence.

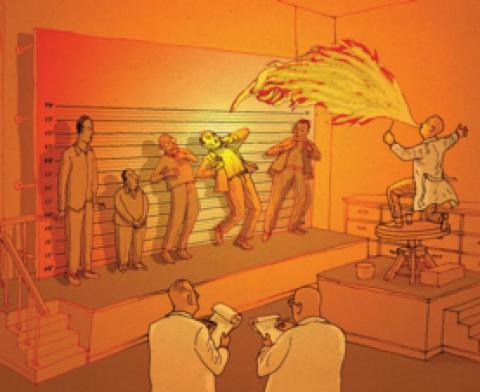

The conference was organized in response to a 2009 publication by the National Research Council entitled Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward, which the U.S. Congress commissioned when it became clear that DNA was the only (barely) reliable forensic science. The report concluded that “the forensic science system, encompassing both research and practice, has serious problems that can only be addressed by a national commitment to overhaul the current structure that supports the forensic science community in this country.” Among the areas determined to be flawed and in need of more research are: accuracy and error rates of forensic analyses, sources of potential bias and human error in interpretation by forensic experts, fingerprints, firearms examination, tool marks, bite marks, impressions (tires, footwear), bloodstain-pattern analysis, handwriting, hair, coatings (for example, paint), chemicals (including drugs), materials (including fibers), fluids, serology, and fire and explosive analysis.

Take fire analysis. According to John J. Lentini, author of the definitive book Scientific Protocols for Fire Investigation (CRC Press, second edition, 2012), the field is filled with junk science. “What does that pattern of burn marks over there mean?” he recalled asking a young investigator who joined him on one of his more than 2,000 fire investigations. “Absolutely nothing” was the correct answer. Most of the time fire investigators find nonexistent patterns, Lentini elaborated, or they think a certain mark means the fire burned “fast” or “slow,” allegedly indicated by the “alligatoring” of wood: small, flat blisters mean the fire burned slow; large, shiny blisters mean it burned fast. Nonsense, he said. It may take a while for a fire to get going, but once a couch or bed burns and reaches a certain temperature, you are not going to be able to discern much about its cause.

Lentini debunked the myth of window “crazing” in which cracks indicate rapid heating supposedly caused by an accelerant (arson). In fact, the cracks are caused by rapid cooling, as when firefighters spray water on a burning building with windows. He also noted that burn marks on the floor are not the result of a liquid deliberately poured on it. When a fire consumes an entire room, the extreme heat burns even the floor, along with melting metal and leaving burn marks under a doorway threshold, which many investigators assume implies the use of an accelerant. “Most of the ‘science’ of fire and explosive analysis has been conducted by insurance companies looking to find evidence of arson so they don't have to pay off their policies,” Lentini explained to me when I asked how his field became so fraught with pseudoscience.

Itiel Dror of the JDI Center for the Forensic Sciences at University College London spoke about his research on “cognitive forensics”—how cognitive biases affect forensic scientists. For example, the hindsight bias can lead one to work backward from a suspect to the evidence, and then the confirmation bias can direct one to find additional confirming evidence for that suspect even if none exists. Dror discussed studies that show “that the same expert examiner, evaluating the same prints but within different contexts, may reach different and contradictory decisions.” Not just fingerprints. Even DNA analysis is subjective. “When 17 North American expert DNA examiners were asked for their interpretation of data from an adjudicated criminal case in that jurisdiction, they produced inconsistent interpretations,” Dror and his co-author wrote in a 2011 paper in Science and Justice.

No one knows how many innocent people have been convicted based on junk forensic science, but the National Research Council report recommends substantial funding increases to enable labs to conduct experiments to improve the validity and reliability of the many forensic subfields. Along with a National Commission on Forensic Science, which was established in 2013, it's a start.

*SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN AND HENRY HOLT ARE AFFILIATES

Michael Shermer is publisher of Skeptic magazine (www.skeptic.com). His new book is The Moral Arc (Henry Holt, 2015). Follow him on Twitter @michaelshermer

This article was originally published with the title "Forensic Pseudoscience."

Spread the word