By Dennis Boyles

Knopf, 439 pages

Hardcover: $30.00; E-book, $14

June 7, 2016

ISBN 13: 9780307269171 ISBN10: 0307269175

There was a joke in encyclopedia circles that went something along the lines that of the tens of millions of words in the Encyclopædia Britannica print edition, its readers understood only a tenth of them, and the remainder were the ones used by other encyclopedias. Journalist, columnist and author Denis Boyles, who grew up in Southern California, can relate.

"I was taught in high school that you started (a report) with the Britannica to find out how much you didn't know," he states. "Then you (turned to the more accessible) Americana, World Book and Funk & Wagnalls encyclopedias until you could fathom at least enough to get (writing)."

Boyles has written "Everything Explained That Is Explainable," a definitive and meticulously researched chronicle of the creation of the Encyclopædia Britannica's Eleventh Edition, published in 1910-1911. That edition comprised 44 million words and 29 volumes, an unprecedented publishing achievement that Hans Koening in The New Yorker called "the last great work of the age of reason."

How was the Eleventh Edition different from previous editions of the encyclopedia? It was, Boyles writes in his book, an encyclopedia for the Edwardian age and "an essential snapshot, not a preview, of a very modern era." The Eleventh Edition boasted entries by some 1,500 named contributors - 35 of them women - including such personages as John Muir, T.H. Huxley, Gertrude Atherton, Frederick Jackson Turner and Bertrand Russell.

Horace Everett Hooper, publisher of the 10th, 11th and 12th Editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

credit: Universal History Archive / Getty // Chicago Tribune

"It was more than a feat of writing," Boyles said in an email interview from France, where he teaches at a Catholic university in La Roche sur Yon and co-edits the venerable Fortnightly Review. "It is an amazing feat of editorial excellence. While many other more modern encyclopedias have appeared, the Eleventh is definitely the high-water mark of this kind of publishing. Hugh Chisholm, the editor of the Eleventh, made a contribution as lasting as Shakespeare in establishing scientific and technical 'progress' as the universal metric. Progress is what the Eleventh is about, even though the topic doesn't appear in the Eleventh's list of 40,000 entries. (Progress, Ill., does, however, on one of the maps.)"

Two Americans play pivotal roles in the Eleventh Edition's story. Massachusetts native Horace Everett Hooper became Britannica's publisher, and with ad man Henry Haxton, they tied the then-financially shaky Britannica to the equally tenuous financial situation of The Times, the London newspaper, which enjoyed an impeccable reputation for credibility.

"Hooper and Haxton were precisely the right people in the right place at the right time - a perfect historical moment to marry brash American optimism with the strength of British cultural credibility," Boyles said. "They marketed the Ninth, Tenth and Eleventh with great audacity, American-style." The book's title was one of the exclamatory claims hawked in sales materials.

Encyclopædia Britannica is headquartered in Chicago and the city plays its typically rogue role, in this case in the history of publishing and the creation of the Eleventh Edition. In the early 1890s, the city was a haven for what Boyles calls in his book "rough and ready publishers" whose trade was bootleg versions of books by others, published without paying any royalties (Not even Mark Twain was immune, as he discovered when he learned of illicit copies of "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer" on the market).

Hooper, who moved to Chicago in 1893, was inspired by Britannica's Ninth Edition and its "big ideas illuminated by confident expertise and polished with scholarly dignity," Boyles writes. Hooper and his partner, Walter Montgomery Jackson, ventured to London in 1897 to secure the rights to publish the Ninth Edition with the extra marketing hook of affixing the logo of The Times. The rest is literally history.

Britannica is alive and well. Its last print edition, a 39-volume set, was published in 2010. It is now a completely digital company, at www.britannica.com.

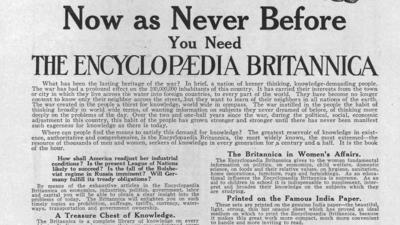

An Encyclopaedia Britannica advertisement from the Sears Roebuck Company from 1922.

credit: Smith Collection/Gado / Getty // Chicago Tribune

"Ours is a bound past but it's buried as far as we're concerned," said Michael Ross of SVP Britannica Digital Learning. "If Britannica had continued along the same path with a set of A-Z volumes, it would not exist today. The correct paradigm for contemporary scholars and information seekers is a constantly updated store of engaging, professionally written, edited and curated material. We don't even call it an encyclopedia anymore."

The Eleventh Edition now is in the public domain and is available to peruse online. For $10,850, you could buy your own edition on www.biblio.com or for as little as $300 on eBay. Its legacy, Boyles considers, is "that credibility sells. It was a product made specifically to satisfy a perceived need. The 19th century was a pretty confusing (time) for the people who lived in it. The Eleventh helped them make sense of their world they inhabited. Wikipedia may have made a physical encyclopedia obsolete, but what Wikipedia lacks is what made the Britannica great: undisputed authority. There is still a market for that - in fact, more than ever. But the politicization of authority makes the thing quite elusive."

[Donald Liebenson is a freelance writer.]

A version of this article appeared in print on June 12, 2016, in the Printers Row section of the Chicago Tribune with the headline "The story of the book that explained the world - Encyclopaedia Britannica's Eleventh Edition was the high-water mark for print references, writes Denis Boyles"

Spread the word