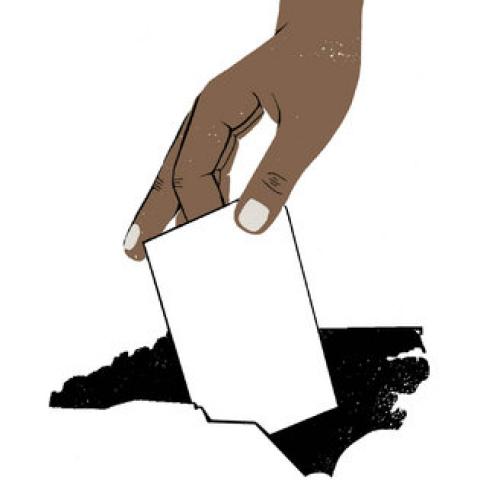

The scurrilous attempt by North Carolina Republicans to suppress the rising power of black voters was struck down on Friday by a federal appeals court that concluded that the state’s voting strictures “target African-Americans with almost surgical precision.”

The decision means that the voting power of black citizens in the important swing state will not be hobbled in November by a repressive 2013 law that the court found was steeped in blatant racism, in violation of the Constitution. “Because of race, the Legislature enacted one of the largest restrictions of the franchise in modern North Carolina history,” the court ruled.

The court, in finding that the law was designed as a deliberate tool to reduce the African-American vote, is the latest to beat back attempts by Republican statehouses to interfere with minority and new voters.

This month, a federal appeals court blocked the voter identification law in Texas, a law that had the effect of disenfranchising hundreds of thousands of people, with a disproportionate impact on black and Latino voters. And a federal court in Wisconsin this month found new voters suffered discrimination under a strict new photo ID law passed by the Republican-controlled Legislature.

Republicans in North Carolina, as in the other states, argued that widespread voter fraud justified the law. However, research studies have shown voter fraud to be statistically minuscule. The North Carolina law had imposed new photo identification requirements on voters and ended procedures favored particularly in black and Democratic political drives, including allowing voter registration on Election Day, and early voting. It also blocked out-of-precinct voting and preregistration of 16- and 17-year-olds.

Significantly, the appeals court noted that the restrictions were enacted by the state within weeks of the Supreme Court ruling that struck down a crucial part of the Voting Rights Act — the requirement that states with histories of racial discrimination obtain preclearance from the federal government for any voting changes. The Legislature moved quickly, the appellate judges found, and first “requested data on the use, by race, of a number of voting practices.” The General Assembly then enacted an “omnibus” bill of restrictions, “all of which disproportionately affected African-Americans,” the court found.

The court also noted that Republican lawmakers were swift to respond “in the immediate aftermath of unprecedented African-American participation” in 2012, which is particularly troubling in state with a history of racially polarized voting. If the voting restrictions had not been struck down, they would have been a sizable hurdle for black voters.

Legal challenges against similar voter-suppression laws in other states are making their way through the federal courts. Any and all these could be crucial in securing a fair and credible election result in November.

For all the lofty rhetoric the nation heard in the last two weeks about democracy at the Republican and Democratic Party conventions, these recent federal court decisions show the grimier reality of politics and the bitter struggle for basic fairness beyond the national spotlight. The black voters of North Carolina have won a major victory and will now have a better chance of making a difference come November.

Spread the word