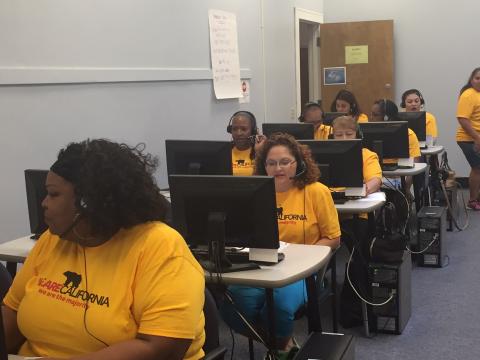

The callers have been organized by the Los Angeles community organization SCOPE (Strategic Concepts in Organizing & Policy Education). Outside it’s blazing hot but it’s cool inside the phone bank room in the basement of the converted fire station where SCOPE has offices. The aroma of fresh coffee wafts around and walls hold images of past SCOPE victories. There are also photos of activists with now-Congresswoman Karen Bass and smiling community people — arms draped over each other’s shoulders after a successful minimum wage vote at the L.A. City Council.

Phone bank laptops automatically dial up the registered voters that SCOPE has been in contact with over several years—nearly 150,000 of them. The caller waits for a beep signaling a connection, then speaks into a headset mic and goes into action.

The mission this evening: ask each voter what that person thinks about three particular propositions–Prop. 55, which continues a flow of $6 billion to schools and other social infrastructure; Prop. 56, which passes a $2 per-pack tobacco tax to reduce young peoples’ smoking and Prop. 57, which reforms sentencing policies for nonviolent juveniles.

The callers ask voters to vote yes on these three measures. The program records the answers, which go into SCOPE’s database. The “yes” votes will receive another contact, maybe two or three, to make sure of Election Day turnout. That will be recorded as well—data for the next election.

Reba Stevens is working the phone bank. She’s been a SCOPE activist ever since someone knocked at her door years ago to ask her opinion about what her community needed.

She smiles before responding to each pickup on the other end.

“Well, I’m hauling oats, Sugar Pie,” she laughs in response to a how-are-you question. “He called me ‘sugar pie,’” she says softly to her co-worker with a little laugh. Then she’s all business and talks up the three propositions.

Connection is key and, Stevens says, When she’s phone-banking from a script, “I don’t share the info as it’s written. What I’m sharing is my own personal experience. Even at a phone bank. You just have to have the information and provide accurate information.” But it’s critical to connect with a voter’s own experience.

Conversations like Stevens’ are going on by phone and on front doors across California. Outside the glare of presidential election coverage, from the Bay Area to the border, local organizations like SCOPE, Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE) and Communities for a New California, and over a dozen more, are fielding thousands of volunteers and staff in modestly-funded but well-equipped operations to reach out to local voters.

The local organizations are all part of the statewide alliance known as California Calls, which was formed in 2003 to coordinate a winning strategy that shifts the California electorate to reflect the Golden State’s increasingly young, Latino and immigrant demographic. That year, Anthony Thigpenn, a nationally recognized organizer, brought California Calls together by convening organizations from the Bay Area, San Jose, Los Angeles and San Diego. Separately from SCOPE, which is a California Calls anchor organization, he later created successful field campaigns for former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Congresswoman Karen Bass and State Senator Kevin de León.

California Calls’ target group comprises the most voters with the most to lose – but with the least connection with the present electoral system. A March 2016 study by the Public Policy Institute of California found that likely voters in California tend to be older, white, college-educated, affluent and homeowners, which affects their views— voters who favor paying down state debt over restoring services.

Many disengaged voters are renters, many work several jobs and struggle with language issues. It takes a concerted effort to connect in a way that speaks to issues in a way robocalls every four years can’t.

So California Calls goes grassroots. It doesn’t do mailers that arrive every election season only to be tossed. Affiliate organizations are in touch with residents year-round—what organizers call the “secret sauce” that boosts turnout. By November 8, 2016 the local organizations affiliated with California Calls —16 organizations in 14 counties — will, based on their projections, have contacted over 250,000 new and infrequent voters by phone and face-to-face, and anticipate moving 135,576 to the polls in support of Propositions 55, 56 and 57. Their voter mobilization work is supported by the California Calls Action Fund, (a 501(c)(4) nonprofit entity that is permitted to do electoral work.

During each election cycle California Calls has inched up the numbers of voters in the areas where member organizations have been working.

Thigpenn’s alliance, in turn, became a partner in the Million Voters Project, a consortium of six statewide groups pledged “to engage and turn out one million voters by 2018.”

The Million Voters partners, Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE), Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA), Mobilize the Immigrant Vote (MIV) and PICO California (People Improving Communities through Organizing) all represent constituencies under-represented at the polls—but who will get there if they feel connected.

“Our model is to is to do large-scale voter outreach even when there’s not an election,” says Karla Zombro, California Calls’ field director. “That’s why it’s possible in 2016 to reach a quarter of a million people. We’re not creating a machine—we already have the machine and keep it well-oiled.”

The other part of the machine is equipping local organizations with technical support—high bandwidth, technical support, data management. California Calls supplies that. “No one organization could do it—but when you scale it up small organizations can afford it,” Zombro says.

The organizing model is not aimed at a single victory but rather changing the electorate to look more like California’s young and growing “minority-majority”—part of California’s changing demographic.

Those are the people frequently left out of the policy discussion, says Raphael Sonenshein, Executive Director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs, who follows California Calls’ work.

“As everyone knows, Prop. 13. has a stranglehold on public investment,” that affects the young people whose families depend on schools and other social infrastructure, Sonenshein observes. “Nobody has asked them their opinion on public investment, on tax policy.”

The state electorate, he says, has been divided on tax policy: bring in a new block of voters and election outcomes can shift along with the demographics.

“The issue of politics often comes down to investing in the younger generation,” says Tom Hogen-Esch, political science faculty at Cal State Northridge, whose course work and writings cover California public policy, race, ethnic and urban politics. Researchers have seen the trend throughout the world in countries that have become more diverse: “If the younger generation is not seen as sufficiently similar, we are not going to invest.”

That sums up the voter dynamic in California—the younger generation is too “different”—Latinos, low-income renters—where white voters make up 60 percent of likely voters in a state where the adult Latino population is 34 percent but with a dismal turnout of 18 percent. Same for young adults–at one-third of the state population they vote at a rate of 18 percent.

“Demography is not destiny,” Sonenshein says. To get voter turnout that reflects the real electorate, organizers need to create nontraditional, not once-in-four-years ways to engage. “You have to hunt where the ducks are. If you ask young people what they care about they’ll talk about everything but the election.”

California Calls has seen a steady response to their ongoing engagement work. In 2010 voters deliberated on Prop. 25, a measure to allow the legislature to pass a budget with a simple majority and 63 percent of those California Called identified as supporters turned out – four percent higher than overall state voter turnout. During the 2012 elections California Calls Action Fund mobilized 440,000 voters in support of the funding measure Prop. 30 to restore funding for education and health care. Along with the Reclaim California’s Future coalition, the alliance says it increased voter turnout six percent to provide the margin that won 55 percent of the vote.

Since then, California Calls has identified 620,000 voters who support tax equity in the state—and who will be contacted and cultivated again before the next election cycle.

It may take long-term persistence — Prop. 47 on the November 2014 ballot reclassified some felonies -drug possession, forgery– to misdemeanor offenses—it reduced sentences and some of the stigma that makes it tough to land a job after incarceration. Supporters identified by California Calls organizations turned out at 54 percent rate of the people they contacted. The overall turnout was 42. 2 percent.

“Civic engagement!” exclaims Pablo Rodriguez, executive director of Communities for a New California, a California Calls affiliate that works in the rural farming communities in the San Joaquin, Imperial and Coachella valleys.

He’s speaking on the phone from his Fresno office, where phone bankers call for three and a half hours a night with a goal of reaching 40 voters each. But organizers and activists knock on doors between elections to talk to neighbors “about curbs, gutters, street signs or –” Rodriguez says wryly, “the lack of them.” When the election comes around “We’ve already been there. We’re a trusted messenger.”

Bobbi Murray has reported on politics, economics, police reform and health-care issues for Los Angeles magazine, L.A. Weekly and The Nation.

Capital & Main is an award-winning online publication that reports from California on the most pressing economic, environmental and social issues of our time. Our mission is to expose threats to the public interest and advance progressive ideas and policies in the nation’s most populous state and one of the world’s most influential centers of commerce, culture and technology.

Spread the word