Harry Belafonte's New York was a lot like yours and mine. He was born in Harlem, got his first singing gig through Lester Young, his first acting role in a company with Sidney Poitier and his first lessons in a class with Marlon Brando, Rod Steiger, Bea Arthur, Elaine Stritch and Tony Curtis. He met the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a Harlem church basement through Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and met W. E. B. Du Bois through Paul Robeson; his uncle Lenny, who ran a numbers racket, introduced him to the elite of Harlem's gangsters. He took Nelson Mandela to Yankee Stadium, planned an Amos and Andy movie with Robert Altman and, at 89, he was a co-chairman of the Women's March on Washington last month, along with Gloria Steinem, though his health kept him from the event.

Mr. Belafonte could tell you a thing or two about New York.

He has been the best-selling singer in America and a pillar in the civil rights movement. But these days, he is anxious about the movement he helped build and about his role in the new era.

"When I took up with Martin," he said, "I really thought, two, at best three years, this should be over. Fifty years later, he's dead and gone, and the Supreme Court just reversed the voting rights, and the police are shooting us down dead in the streets. And I look at this horizon of destruction, and I watch the black community by our state of being mute - we have no movement. I don't know where to go to find the next Robeson. Maybe I don't deserve a next one. Takes a lot of courage and a lot of power to step into the space and lead a holy war."

Mr. Belafonte, who will turn 90 on March 1, speaks in a hoarse rasp that ended his singing career in 2004; he gets around using a three-wheeled walker since having a stroke around that time. The stroke dumped him on the sidewalk on 72nd Street but did not dull his sense of humor. "I missed the opportunity," he said, "but if I had a paper cup, I could have made a fortune." He wore a down jacket indoors and drank water because his blood thinner made him thirsty. He looked good.

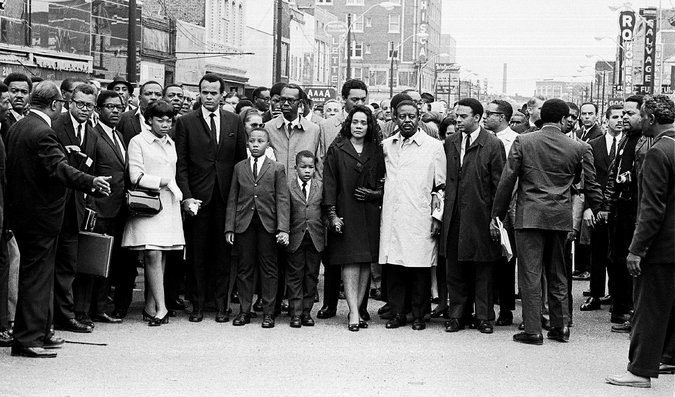

Mr. Belafonte, fifth from the left, marching in Memphis with Coretta Scott King and her family four days after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

Credit Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images // New York Times

Of his role now, he said: "I'm trying to sort out what that is. There's just so much left that's in my basket of possibilities. I'm not as young as I feel, or as young as I would consider myself to be. The 90 figure is a blur. But I do know that if there's anything left for me to do, I had best hurry up and do it, because time is not an ally."

In a long interview in his apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, he talked about people he had known and the city they left behind. "One of my big difficulties in dealing with 90 is when I start to think about, Where is so and so?" he said. "I kind of treat it like, `You don't talk to me anymore, we don't do like we used to do, what happened?' `Well, very simple: I'm dead.' They're all gone. Ossie Davis, there's no more Saturday call, no more poker. All my friends. It's amazing.

"This last period of my life is absolutely fascinating to me. I'm like, I'm outside, looking at a story, and I have no idea what's on the next page - none."

Mr. Belafonte was in a reflective mood, recalling the Harlem apartments his mother fled in the middle of the night to avoid paying back rent, and the majesty, years later, of his own 21-room apartment on West End Avenue, where guests included Dr. King, John F. Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt and Ralph Abernathy.

"I often look at the journey, and I don't get it," he said. "I really don't. I have lasted longer than I understand why. I often feel that there must have been something that I should've done that I didn't do. But I can't identify what it is that I didn't do. That's the first difficulty. And the second is, what makes you think you're it?

"This is not modesty. This is part of a bigger search for me. What was all this about? Why?"

He was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr., and dropped out of school in ninth grade, frustrated by what was later recognized as dyslexia. His parents, both light-skinned immigrants of mixed race, dodged landlords and immigration officials by changing the spelling of the family name, and avoided housing covenants by claiming to be Hispanic. Harry was drawn toward his uncle's numbers business, which his mother forbade.

"Everybody in that world were role models in how to survive, how to be tough, how to get through the city, how to con, the daily encounters," he said. "But my mother saw to it that unless I wanted to live life absent of testicles, she wasn't going to have me follow her brother Lenny. Somewhere in there is a Sholem Aleichem - a rich story to be told of the lore of that time. My uncle was very respected by those who worked for him. And my mother was very dependent on him, because when things really hit the skids, she could always go to him and get 20 bucks or get the dinner or get us through the weekend."

From its rough beginnings, Mr. Belafonte's life evokes the dynamism of midcentury New York. He was working as a janitor's assistant when a customer gave him tickets to an American Negro Theater production, and when he volunteered to help as a handyman, he soon found himself onstage with Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis and Mr. Poitier. Early audiences included Mr. Robeson and Mrs. Roosevelt, who would become friends. He was learning about communism and global liberation movements, and also about life as a handsome man in New York.

This record album topped the Billboard album charts for six weeks in early 1956.

"I loved Ruby," he said. "She was very smart marrying Ossie, because the rest of us came after her like a herd of thugs. She was smart. She dumped us."

For Mr. Belafonte, New York in the late 1940s meant visits with Mr. Robeson to Dr. Du Bois, and jazz clubs in Midtown, where he got to know Mr. Young, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Max Roach. When Mr. Young tapped him to sing between sets at the Royal Roost, Mr. Belafonte found himself with a career he had never sought.

"I started this thing," he said, "and it became so attractive to the public it scared the hell out of me. It really did. Wait a minute, this thing is bigger than I can handle. I'm not a pop singer. I'm here reading Shakespeare and dissecting `Othello,' and looking at `Macbeth.' Being a pop singer is not what it's about. And I quit."

It didn't last. With two friends he opened a short-lived burger joint in Greenwich Village, which brought him to the Village Vanguard and the performances of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, who mixed lefty politics with songs rooted in daily life. By the time Mr. Belafonte made his debut at the Vanguard, earning $70 a week, it was with a repertoire of folk songs and international songs that included "Hava Nageela." The club soon could not contain his audience.

Singing with Nat King Cole in 1960.

Credit Bettmann Archives, via Getty Images // New York Times

"The till," he said, "was just beginning to carry a jingle."

The pieces fell into place: He was said to be the first solo singer with a million-selling album and was one of the first African-Americans with his own television show in 1959. "Hava Nageela," he said, made him "the most popular Jew in America." (His paternal grandfather was Jewish, but Mr. Belafonte only sang the part.) His good looks and light complexion made him palatable to white audiences, even as his background and politics were alien to them. When Dr. King asked to meet him, he said: "I threw my lot in with him completely, put a fortune behind the movement. Whatever money I had saved went for bonds and bail and rent, money for guys to get in their car and go wherever. I was Daddy Warbucks." He helped organize the third march from Selma to Montgomery, recruiting entertainers like Joan Baez, Tony Bennett and Mahalia Jackson for a concert in Montgomery.

"Dr. King gave me the space to pursue my rebellion against the system," he said. "They came after Dr. King with great vigor, and they didn't get him. They came after me with great vigor; they didn't get me. If they'd gotten me, I'm not quite sure what they'd have done with me."

The civil rights leader also taught him how to accept his own death, Mr. Belafonte said. "Dr. King had a tic, a nervous disorder that would present itself out of the blue," he said. When the tic later seemed to disappear, Mr. Belafonte asked his friend about it. "He said, `I made my peace with death,'" Mr. Belafonte said. "He wasn't distracted or preoccupied. If it was to be, it was to be. I adopted the same thought. I can't just live all day long waiting for something to happen that either will happen or will not happen."

On a long afternoon interview before Election Day, Mr. Belafonte reflected on his disappointments since Dr. King's murder. In his late years, as he cut back on public appearances, he has become almost surgical in delivering rebuke bombs. He called former Secretary of State Colin L. Powell the "house slave" of the Bush administration and started a feud with Jay Z that lasted three years, telling The Hollywood Reporter in 2012 that performers like Jay Z and Beyonc, "have turned their back on social responsibility." Jay Z fired back in song: "Mr. Day-O, major fail."

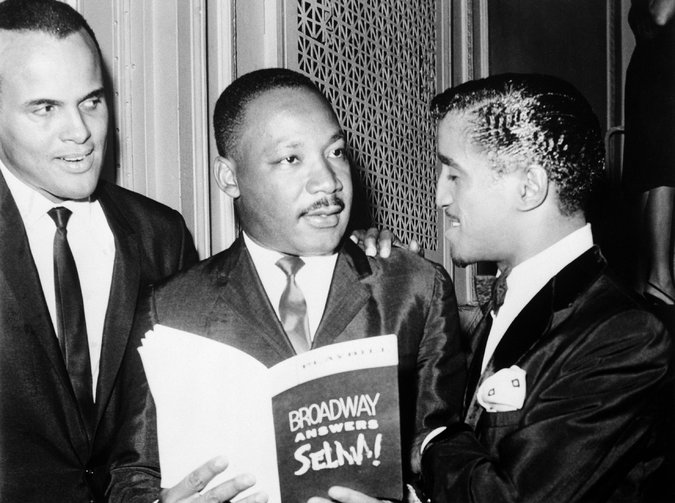

With the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sammy Davis Jr.

Credit Bettman Archives, via Getty Images // New York Times

On this fall afternoon before the election, he said that the rise of Donald J. Trump alarmed him, but not as much as the passion and numbers of Mr. Trump's supporters. "I've never known this country to be so" - he paused before saying the word - "racist as it is at this moment," he said. "It's amazing, after all that we have been through."

Though he was encouraged by the energy in the Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements, he felt that both lacked an ideology to make real change. But he was hardest on people of his generation, who he said did not follow through on what they started.

"The rewards for what we achieved in the civil rights movement have more than corrupted the movement," he said. "What happened in the black community, when they finally won the right to vote, they picked the ones who they knew, which is not to be unexpected. But the ones they knew were all the leaders. They knew Jesse.

"They knew Andy Young. They knew John Lewis. They pushed them right into the electoral political sea. Go run the state. Go run the government. Become a senator. I even encouraged them to do that as the next step to the civil rights movement. When you get the opportunity for that presence in government, let's fill it with our best. Well, our best were guys in the movement. Once they went off into electoral politics, they abandoned the community. They abandoned that work. They abandoned that developmental process."

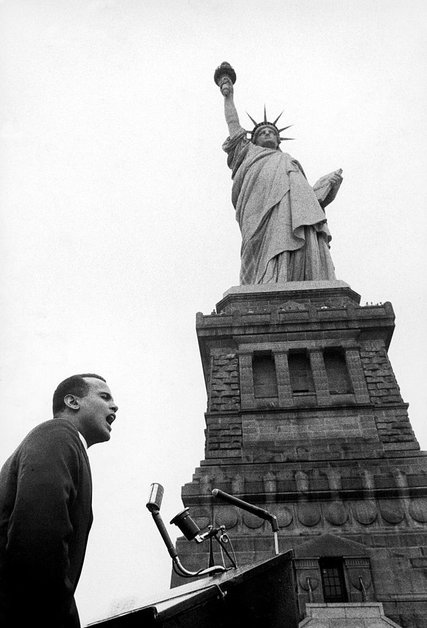

Speaking at a civil rights rally at Statue of Liberty.

Credit Al Fenn/LIFE, via Getty Image // New York Times

By January, after Mr. Trump's election, Mr. Belafonte was more focused on the new president, whose coming administration he had compared to a "Fourth Reich." Mr. Trump, he said, was not a break from America's traditions but a resurfacing of energies that have been there all along.

"I look at him as a continuation," he said. "With all of the images that we throw up about our generosity as a nation and so forth, America tends to ignore the fact that there is a parallel history from which we come that's not quite so pleasant. And I think Donald Trump reminds us that that value, that negative component, is still strongly in our midst."

Looking ahead, he said, "I often think about how the German right wing emerged in the '30s and '40s, and what came of that, and I think we're in the same space. Here we are, a highly educated, highly economically secure society. Everything is in our favor, and if everything is in our favor, what is it that we want as a people and as a nation that makes Trump so attractive? Something's askew here, terribly askew.

"I think it's an opportunity for the left to take this wake-up call. We need to be much more radical in what we do and how we do it than we have been up to now. The liberal community has compromised itself out of existence. The black community has been so passive in its response to this onslaught. Labor is strangely silent. All those reverends that were part of the progressive front are no longer heard from in any appreciative way. And out of that vacuum comes Trump."

Yet Mr. Belafonte was not mired in despair. In his apartment, he has a hallway of photographs of himself with Dr. King and other important figures from his life, with one wall showing them angry or mournful, and on the other wall smiling or laughing. "I love the happy wall," he said. "People never get to see that side."

With his milestone birthday around the corner, he was re-examining moments from his past, counting his fortunes along with his mistakes. New York, he said, still mystified him in its grandness - as unlikely as his own rich life.

"I think there's no city quite like New York," he said, "and I've seen most of the developed cities of the world. I admire this place, its energy. It's the repository of so much history and culture and diversity. I think New York City most represents what it is that America in general aspires to. It's big, it's dense. I've known this city from all of its social arcs. The best that's in America is yet to come. The worst that's in America is yet to come."

For himself, he said, he still had one last act to live out. He just didn't know what it was.

"It's my last chance to say whatever I feel the need to say. And I think I'm formulating what that utterance should be. What have I not said that needs to be said more forcefully and more precisely? There are times we mute ourselves, we censor ourselves because we have this false pride, this need to be liked. Rather than worry about being liked, are you telling the truth, putting your best foot forward? I try to, but there's something missing here, and that's what I'm looking for: What's missing?"

He did not have an answer for his question. But after 89-plus years, one thing is almost certain: When he figures it out, his scratchy voice will make itself heard.

***A version of this article appears in print on February 5, 2017, on Page MB1 of the New York edition with the headline: Harry Belafonte Knows the Score.

Spread the word