The Investigator in Historical and Personal Context

Gerald Gross

The Journal for MultiMedia History

Volume 3, 2000

http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol3/investigator/investigator.html#

Reuben Ship's celebrated radio satire of the work of the US House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and its chairman, Joseph McCarthy, was first aired nationally in Canada by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) on May 30, 1954. For the most part, the drama was reviewed favorably in Canada. In the USA, it was reviewed in a positive light by the New York Times and by the left-wing press (including New Masses), but it was excoriated by the right wing as anti-American propaganda. By mid-June, tapes of the broadcast were circulating in the USA. There, some attempts to broadcast the CBC production on both coasts caused objections from the American Legion and private individuals.

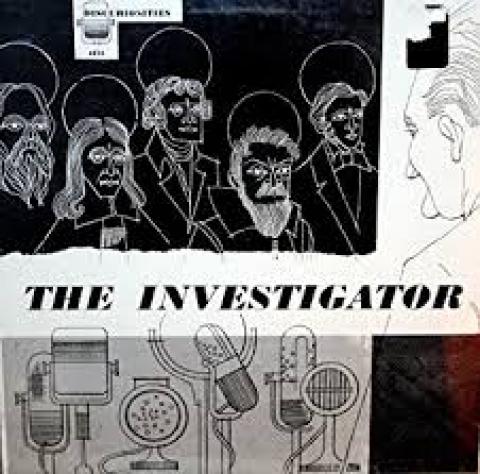

About 100,000 copies of a long-playing record made from the CBC production of "The Investigator" were sold during 1954 and 1955, mostly in the US. The LP appeared on an obscure label named "Discuriousities" created by two enterprising Americans to sell the recording-probably in collaboration with Ship himself. The record was described as communist propaganda by Ed Sullivan in his newspaper column and in other publications; it was given positive notice (again) in The New York Times, which wondered if the satire might cause friction between the US and Canada. The New Republic informed readers that a chuckling President Eisenhower had it played at a meeting of his cabinet. In Ottawa, Hugh Lennard, a Conservative member of Parliament, castigated the Canadian Government for allowing the broadcast. The Australian Broadcasting Company requested broadcasting rights and the production was praised highly when it was aired by the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) a year or so later. The play was widely known in disparate places by a variety of audiences. The controversy around the work relates to many factors, not the least of which was the timing of its broadcast during a high point of the Red Scare following WW II.

The original airing of the play as part of a drama series called CBC Stage occurred while the widely viewed Army-McCarthy hearings were being televised in the U.S. John Drainie, the gifted actor who played the role of the Investigator, drove from Toronto to Buffalo to watch the hearings more than once, which partly explains the uncanny accuracy of his portrayal of the Senator. The ambitious and rambunctious McCarthy was just then in the most highly publicized fight of his political life. So, naturally, a play which imagines him in heaven and the Chairman of a Committee which includes Torquemada, Cotton Mather and Titus Oates, a Committee which sits in judgment of Socrates, Milton, Jefferson and other such champions of liberty and declares them "subversives" worthy of deportation to hell-such a play would quite naturally call attention to itself.

The allusiveness of the play was not its only attraction. The quality of the production was also a factor. CBC Stage was then offering weekly hour-long dramas. Andrew Allen, a very fine director, had gathered a skilled and experienced cast of professionals for these programs. The acting, the provocative original musical score, and, of course, the witty writing all contributed to the impact of the production. Then, too, we ought to remind ourselves that radio was still a very important medium for a range of dramatic entertainment, particularly in Canada where radio was the country's national theater, spanning distances and reaching a sparse population economically.

By 1954 several celebrated espionage cases had been investigated in the USA, Canada and Great Britain; the guilt of a number of spies had been affirmed in courts of law. The Rosenbergs had been executed for treason. Igor Gozenko, the Russian cipher clerk residing in Ottawa, had made a full declaration of his activities on behalf of Moscow. These and other cases, some of which had been conducted in such a way as to powerfully irritate liberals and to harden the views of their opponents, added to the conflict. Some clergy were accused of disloyalty. Loyalty oaths were demanded of teachers in schools and universities as well as of workers in several corporations. Many thought it was their patriotic duty to inform on colleagues whose views seemed sympathetic to communist causes. Blacklisted authors lost their publishers, and others their jobs. The names of hundreds of "reds," "subversives," "sympathizers," "dupes," "pinkos", and more were listed in a infamous publication named Red Channels. It is clear that the political conflict had its personal side as well.

The importance of context to the character of the radio play can be seen in another way. Ship was a Canadian who had lived and worked in Hollywood since 1944. He had been writing The Life of Riley, a weekly comedy series, for nearly a decade when HUAC went to Hollywood a second time, in September, 1951, to investigate subversive activities in the film business. According to their own files, the FBI first noticed Ship in July, 1947 when he gave a speech entitled "Radio in a Free Culture" to a rally in Hollywood. In that speech, Ship attempted to show the power the sponsors of radio programs exercised over program content. Since the organizers of the rally were anti-HUAC, Ship was guilty by association. Ship was also involved in a complex struggle between two unions for power in the rising television industry and his union was seen as left wing in its affiliations. Two witnesses involved in that conflict named Ship a communist at the HUAC hearings, and so when he was called to testify, the Committee was not likely to have been surprised by his antagonistic stance. When the Committee learned that he was a Canadian, dissatisfied with their conduct of the inquiry, he was told that if he didn't appreciate the benefits of America he could go home to Canada.

In fact, soon after the hearing, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) opened his case and called him to a protracted hearing. His defense was unsuccessful, as was his appeal, for which he went to Washington; the order for his deportation from the USA as an enemy alien was given. Ship suffered from osteomyelitis and was hospitalized in Los Angeles for some time, delaying his departure until July, 1953. While still on crutches, he was removed from the hospital, handcuffed, and escorted across the country to Detroit by plane and train. He was placed overnight in a prison hospital where he lay among sick drunks and the dying disorderly. When he was taken across the bridge to Windsor the next day, he felt liberated.

Immediately after his arrival in Montreal, where Ship was born and raised, he wrote to Aubrey Finn, his Los Angeles-based lawyer and friend, describing the harrowing events surrounding of his expulsion. That experience, coupled with the stresses associated with the lengthy period of deportation proceedings, the uprooting of his family from his home in Hollywood, and the memory of his clash with the House Committee on Un-American Activities provided a personal context for writing The Investigator.

In practical terms, too, Ship had cause and occasion to write this scathing play. The HUAC had destroyed his career in Hollywood and there was little opportunity for that degree of success in Toronto where he settled for a year, writing drama for the CBC and advertising copy for a large agency. And so he wrote The Investigator with a powerful and personal sense of the injustice done to him. As he recalled his powerlessness, sitting as the accused before his powerful accusers at HUAC and the INS, he must have honed the edge of his anger. With that in mind, it isn't surprising to find in the play, in his characterizations of the despicable character of the investigator's committee "Up There," some of the legal phrases found in the record of his INS hearing.

For the most part, then, Ship's satire comes out of his personal experience which was rooted in the conflicts of the history of his time and place. The satire is retribution in the form of ridicule directed at his tormentors whom he judges using criteria drawn from his knowledge of the humanistic tradition and for the sake of civil behavior.

Spread the word