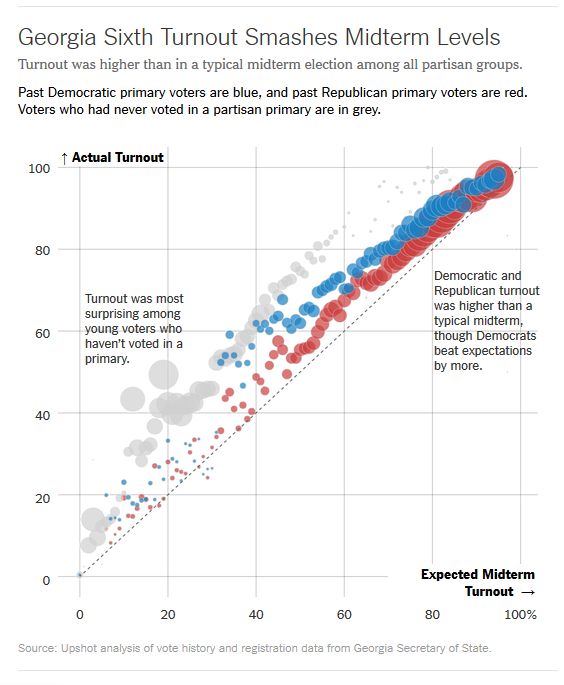

The special election in Georgia’s Sixth Congressional District was the most expensive House race in history. In the end, it produced probably the strongest Democratic turnout in an off-year election in at least a decade, according to newly released voter turnout records.

It is perhaps the strongest evidence yet that Democrats won’t be at an acute turnout disadvantage in next year’s midterm elections, as they were in the last two.

Jon Ossoff, the Democrat, still lost by nearly four percentage points. But he brought a surprising number of irregular young and nonwhite voters to the polls, even if the electorate was still not as young or diverse as it was in 2016.

Black turnout, though, lagged in the second round of voting. The race suggests that Democrats will probably be disappointed if they hope to increase the black share of the electorate with traditional mobilization efforts alone.

These findings are based on vote history data from the Georgia Secretary of State. It provides an individual-by-individual account of who voted and who did not.

The records indicate that past Democratic primary voters turned out at nearly the same rate as past Republican primary voters (Primary vote history is the most readily available measure of partisanship in a state without party registration, like Georgia.)

Over all, 75 percent of voters who last voted in a Democratic primary turned out in the second round of voting, compared with 76 percent of those who last voted in a Republican primary. The turnout rate among voters who have never voted in a primary was 34 percent.

This might not sound like a great Democratic turnout, but it is pretty rare for the Democratic turnout rate to roughly match the Republican turnout rate, at least in a high-turnout election. Certainly, that’s been true in Georgia’s Sixth: In 2014, Republican primary voters turned out at an eight-point higher rate than Democratic primary voters did, 77 percent to 69 percent. In the 2016 election, it was a three-point gap, 89 percent to 86 percent.

It has been true nationwide as well. According to an Upshot analysis of data from L2, a nonpartisan voter file vendor, the Democratic turnout did not match the Republican turnout rate in any recent national election, including 2006, 2008 and 2012. Iowa has complete official turnout history dating to 1982, and Democrats haven’t exceeded the Republican turnout rate in any of the general elections over that period in the state.

The point is: This is about as good as it gets for Democrats, at least in a reasonably high-turnout election (unusual and imbalanced turnout patterns are more common in lower-turnout contests, when even a slight enthusiasm edge translates to a big change in the composition of the electorate).

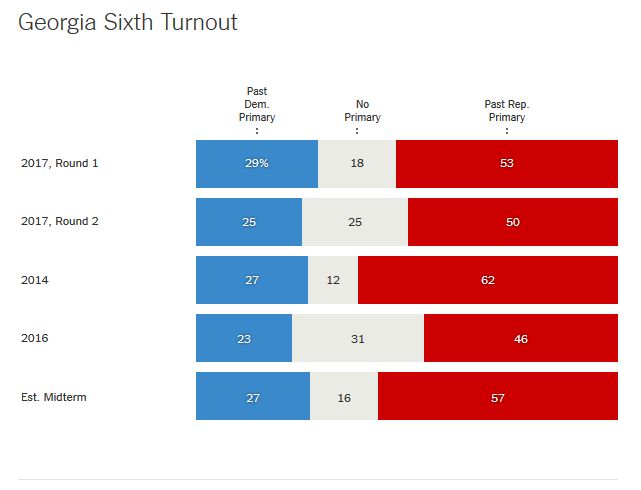

The result is that the partisan makeup of the electorate — past Republican primary voters outnumbering Democrats by 24.5 points — was a lot more like the 2016 presidential election than the 2014 midterm electorate, or even our estimates for a more “typical” midterm electorate.

The bad news for Democrats is that the Republican turnout edge was larger than in the first round of voting in April, when Republican primary voters outnumbered Democrats by 23.7 points. That’s not because Democratic turnout was weaker in the first round than the second round; turnout was up across the board. It’s just that the Republican turnout, which was particularly weak in the first round, increased by more than the Democratic turnout increased.

Mr. Ossoff countered the increased Republican turnout with an equal increase in turnout among voters who have never voted in a primary, who most likely backed him by a big margin. It’s an inescapable conclusion: There isn’t another way he could have received 48 percent of the vote in an electorate where Republican primary voters outnumbered Democrats, 49 percent to 25 percent. Demographics also offer clues that these voters backed Mr. Ossoff; the voters who haven’t voted in a primary are far younger and more diverse than those who have.

Over all, voters who had never voted in a primary represented 25 percent of the electorate, up from 18 percent in the first round.

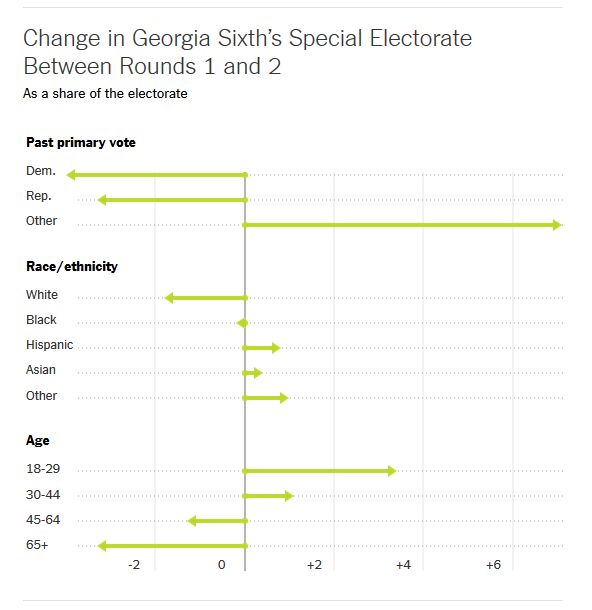

The nonwhite and youth share of the electorate also increased. Over all, 18-to-29-year-old voters represented 10.6 percent of the electorate, up from 7.4 percent in Round 1, and more than halfway between the 6 percent in the 2014 midterm elections and 13.6 percent in the 2016 presidential election. It was also up from the 2016 presidential primary, when they represented 7.9 percent of voters in the district.

Similarly, the white non-Hispanic share of voters (as indicated on their voter registration form) fell to 74 percent of the electorate, down from 75.6 percent in the first round of voting. That, too, was about halfway between 2014, when white voters represented 79 percent of the electorate, and the 2016 presidential electorate, when 71.4 percent of voters were white. Turnout of Asian-American voters, in particular, was high — basically matching their share of the 2016 electorate.

There was probably one big exception: Mr. Ossoff did not benefit from such a favorable turnout among black voters. They represented 9.3 percent of voters, the same percentage as in the first round of voting. It was also lower than the 9.4 percent from 2014 or 10.6 percent in 2016.

The stability of the black share of the electorate is pretty striking. In theory, higher turnout ought to have increased the black share of the electorate as a matter of course, just as it increased the share of other low-turnout young and nonwhite, nonblack voting groups. Our pre-election estimate was that black voters would represent 10 percent of the electorate in the second round of voting; our estimate before the first round was 9.5 percent.

From the perspective of campaign mechanics, this was a prime opportunity for Democrats: two elections for field organizing, millions of dollars, a high-profile national race, and great data (the same data used here makes it easy for campaigns to target black voters). Even so, black turnout lagged.

Taken together, these two factors — higher Republican turnout and higher youth and nonwhite turnout — roughly canceled out.

Democrats, unsurprisingly, are disappointed by losing in Georgia. The recriminations are already underway. There are, undoubtedly, things that Democrats can hope to do better next time. There always are.

But the turnout probably isn’t the thing that should keep Democrats up at night. The strong Democratic turnout fits a longer-term pattern of Democrats matching G.O.P. turnout in midterm elections when the Republicans hold the White House, essentially yielding the same partisan breakdown as a presidential election. If the same thing happens in 2018, Democrats will be much better off than they were in 2014 or 2012.

The bad news for Democrats, of course, is that even this sort of turnout is no guarantee of victory. The battle for control of the House will be fought in large part in Republican-leaning districts like Georgia’s Sixth, and a strong Democratic turnout alone probably won’t be enough to win a high-turnout election. In many districts, the Democrats will be burdened by the additional challenge of mobilizing young, nonwhite and perhaps especially black voters.

Even a very impressive turnout — like the one in Georgia’s Sixth — might still leave them with an electorate no more favorable than the one that elected Donald J. Trump in November.

Spread the word