On Sunday, President Donald Trump took aim at one of his favorite targets: Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is hoping to unseat him in 2020. Responding to a video Warren posted on Instagram in which she drinks a beer in her kitchen and introduces her husband, Trump tweeted:

“If Elizabeth Warren, often referred to by me as Pocahontas, did this commercial from Bighorn or Wounded Knee instead of her kitchen, with her husband dressed in full Indian garb, it would have been a smash!”

Trump has long attacked Warren for claiming Cherokee and Delaware ancestry, belittling her as “Pocahontas” and, more recently, challenging her to prove her claims using a DNA test. But his invocation of Wounded Knee—one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history—is a new low.

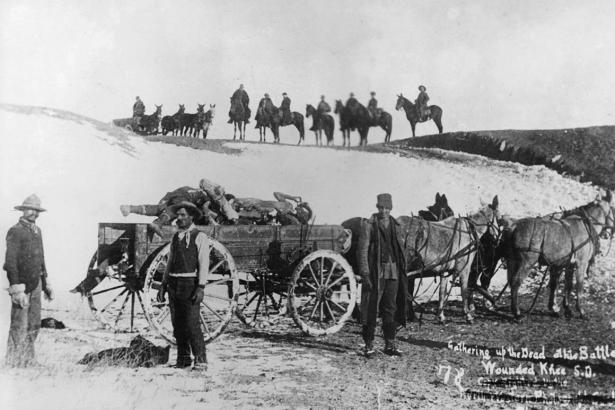

On December 29, 1890, the U.S. 7th Cavalry massacred hundreds of Lakota near Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. It was hardly the largest settler massacre of Native peoples, but it is the most infamous. To Native peoples it has long been a symbol of U.S. brutality, a reminder of the immorality of a nation that claimed it was bringing civilization but instead brought a slaughter.

Wounded Knee was the culmination of decades of tension and conflict on the Plains as Native peoples resisted American efforts to expropriate their lands and confine them to reservations. The U.S. government forced unfair treaties on tribal nations, wrenched away their land, failed to live up to its own treaty obligations, and failed to stop settler squatters from invading Native lands. In the late 1880s, a politically potent spiritual movement that Americans called the Ghost Dance grew from the teachings of the Paiute prophet Wovoka and caught fire among the Native peoples of the Plains. As historian Tiffany Hale recounts, it was a complex movement of beliefs and practices offering solace, hope and courage, but American fears fixated on one notion within it: that the proper practice of a prayerful dance would hasten the departure of the whites and the return of lands to Native control and Native ways of life.

The movement spurred American fears of an “Indian uprising,” and in December 1890, President Benjamin Harrison ordered the Army to suppress the Ghost Dance and arrest its leaders. When the U.S. Indian police arrived to arrest the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man Sitting Bull, a Lakota shot a policeman, and the police shot and killed Sitting Bull. Fearing further violence, the Miniconjou Lakota Chief Spotted Elk (also known as Big Foot) decided it was time to move. Under his leadership, a group of Lakota set out across 200 miles of frozen prairie from the Cheyenne River Reservation to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Other Hunkpapa Lakota fleeing the Ghost Dance crackdown joined him and their numbers swelled to around 400 people—mostly women and children.

Members of the 7th Cavalry intercepted the Lakota refugees on December 28, 1890. Ordering them to make camp at Wounded Knee Creek, Army officials demanded they give up their guns. This made Lakota people, who were hunters, vulnerable to violence and hunger. The next morning, after giving up their rifles, the Lakota were subjected to a destructive search operation. Soldiers scoured the camp for hidden guns, tearing apart the women’s bundles, smashing dishes and seizing knives, awls, tent stakes—anything with a sharp edge. During the search, according to several accounts, a man named Black Coyote either did not understand the order to surrender his rifle (he was deaf and did not speak English) or resisted because it was valuable to him. A scuffle broke out, and someone (it is unclear who) fired a shot. Then, the Americans unleashed their firepower.

The women and children ran, but many were gunned down by bullets and cannon shells fired by U.S. soldiers as they fled. Those who made it past the firing lines could find little shelter in the flat and denuded December prairie, and many were murdered by cavalry troops who hunted them down. While a few Lakota men managed to grab a gun or a knife, they were no match for the Army’s strafing and shelling. The slaughter was relentless. American Horse, an Oglala Lakota who spoke to many survivors of the carnage, reported that as little boys emerged from the ravines, they were immediately surrounded and “butchered.” Powder-burns on the dead made a clear case for atrocity: Only guns held close to the body in point-blank executions leave such marks. Historian Jeffrey Ostler concludes, “By the late afternoon, when the firing finally subsided, between 270 and 300 of the 400 people in Big Foot’s band were dead or mortally wounded. Of these, 170 to 200 were women and children, almost all of whom were slaughtered while fleeing or trying to hide.” At least 20 American soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their part in the massacre.

Wounded Knee was an atrocity on such a scale that, in a way, it became a symbol for all the other atrocities. It is no coincidence that Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee is one of the most influential popular books on the larger atrocity that is American policy toward Native peoples, or that Wounded Knee, South Dakota, became the site of militant Native resistance in 1973. So when Trump made light of Wounded Knee, he invoked an episode that still remains raw and powerful in Native memory today.

Not only does his tweet joke about a massacre, his continued taunts reinforce insidious stereotypes about Native peoples, and especially Native women. The popular story of “Pocahontas”—about an Indian maiden in love with a settler man—is itself a Disney fantasy, and one that, as historian Honor Sachs argues, “props up white supremacy.” There’s more. To Trump, real Indians are clearly a defeated remnant of the past, frozen in time at Bighorn and Wounded Knee, wearing “Indian garb.”

Here’s the thing: In 2019, there are over 570 tribal nations in the United States that are recognized by the federal government, in addition to scores of nations that are recognized by state governments or are seeking recognition. Native Americans are modern people living in urban, suburban, reservation and rural communities. As citizens of sovereign tribal nations, Native peoples have rights and responsibilities that are determined by their nations’ distinct governance practices. Tribal governments, for their part, have laws and policies to address the needs of their citizens: Some nations issue passports for their citizens; they run schools, health care facilities, child welfare offices, libraries and museums. The list goes on and on, undermining antiquated ideas about Native peoples that continue to circulate in pop culture.

While Trump’s tweets rely on stereotypes evoking the Disney character and hypersexualized women dressed up as “Poca-hotties” at Halloween, the reality for modern Native Americans, and for Native women in particular, is different. Earlier this month Indian Country celebrated as Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk) and Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) entered the U.S. House of Representatives. At the same time, Native Americans are all too familiar with depressing statistics about Native women who face appalling rates of domestic violence, rape and murder. As Amnesty International reported in its 2007 study Maze of Injustice, Native American and Alaska Native women are 2.5 times more likely to be raped or sexually assaulted than women in the general population in the U.S., and over 34 percent of Native women will be raped in their lifetime. More recently, researchers reported the shocking number of Native women who have disappeared: According to statistics compiled by the Urban Indian Health Institute, 5,712 Native American and Alaska Native women and girls were reported missing in 2016 alone. Native women are also four times more likely than non-Native women to see their children removed from their custody, and Native children are 14 times more likely to be held in state foster care.

You wouldn’t know about the real-world challenges that Native American women face from listening to Trump—or from listening to Warren for that matter. In response to the racist, misogynistic Pocahontas slur that has been aimed at her since 2012—after the Boston Herald published a story reporting that during the mid-1990s Harvard Law School officials “prominently touted Warren’s Native American background”—Warren has mostly sought to protect her own reputation, insisting on the veracity of her family lore.

The one and only time, to our knowledge, that Warren has admitted how destructive the name-calling is—not just to her, but to Native Americans—was in February 2018 when she made a surprise appearance before Native American-elected officials at the National Congress of American Indians. In her speech, Warren compared the Disney film with the “real” story of Pocahontas and then noted that the story has been “twisted” for political purposes. Recalling a November 2017 White House ceremony honoring World War II Navajo code talkers, Warren reminded listeners that Trump had disrespected war heroes when he mentioned Pocahontas in connection to the senator during the solemn event. This was an important moment—Warren noted the disruptive and disrespectful effect these references have. At the same time, it was frustrating. While Warren acknowledged the violence Pocahontas endured during her short lifetime, and she could recognize the manipulation of a young girl’s experience into a racist joke, she never uttered words suggesting she understands this is a slur that targets Native women. And she has been silent since.

If Warren really wants to counter Trump and his gleeful invocation of genocidal violence she should denounce the use of Pocahontas as a racist and misogynist slur. She should use her platform to shift the narrative about Native peoples in the United States, pointing to their enduring sovereignty and the imperative that the American government rectify the harm it has done them. She can draw attention to the recently lapsed Violence Against Women Act, redouble efforts to renew this important legislation and advocate for practical solutions to gaps in jurisdiction and funding that will help Native American women and tribal nations pursue justice. It should go without saying she should abandon and apologize for her talk about her undocumented family lore of Indian ancestry, but she has to go beyond that. It’s time Elizabeth Warren uses this as an opportunity to defend Native women, and not just herself.

Alyssa Mt. Pleasant is assistant professor in the Department of Transnational Studies at the University at Buffalo (SUNY). Her scholarship focuses on History and Native American and Indigenous Studies.

David A. Chang is Distinguished McKnight University Professor of history and chair of the American Indian Studies Department at the University of Minnesota, and author of The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration.

Spread the word