Japanese-American Teens are Confronting History by Visiting World War II Former Incarceration Camps

OG History is a Teen Vogue series where we unearth history not told through a white, cisheteropatriarchal lens.

Making the drive from Los Angeles with her friends, 19-year-old Sydney Takeda didn’t know what would be waiting for her at the Manzanar National Historic Site, where 1 of the 10 incarceration camps that imprisoned Japanese-Americans in World War II once stood.

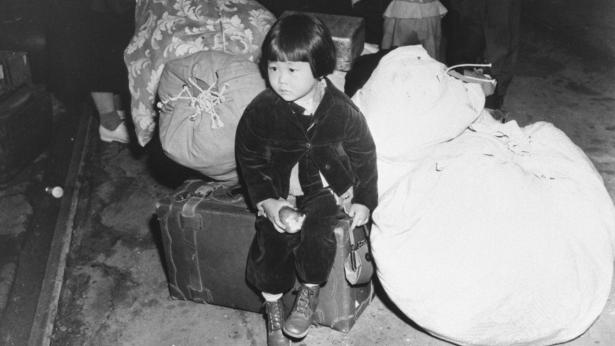

It was an early Saturday morning, but it was already almost 90 degrees out in the desert. Sydney looked out the car window and realized she was seeing what more than 10,000 Japanese-Americans were seeing in 1942 when they had to pack their suitcases, leave their homes behind, and board trains, buses, cars, and trucks that led them into rows of barracks standing behind barbed wire.

“My friends and I were like, ‘There is absolutely nothing out here,’” Sydney tells Teen Vogue. “Lots of thoughts were racing through my mind, like, what would it feel like if I was to be on this train taken to camp, having no idea what was to come, and what would happen to us?”

Sydney was one of over 2,000 people who made the trek to the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains on April 27 for the 50th anniversary of the annual pilgrimage to Manzanar. Held each April, the Manzanar pilgrimage serves to educate the public on an important example of civil rights violations in United States history and to encourage individuals to ensure their fellow Americans’ constitutional rights are never stripped away again.

The Manzanar pilgrimage is just one of several pilgrimages made to former WWII campsites throughout the year. Other camps designated by the War Relocation Authority, the federal agency established specifically to provide for the incarceration of Japanese-Americans, include Poston and Gila River, in Arizona; Tule Lake, in California; Minidoka, in Idaho; Topaz, in Utah; Heart Mountain, in Wyoming; Amache, in Colorado; and Jerome and Rohwer, in Arkansas.

Sydney hoped she would be able to unearth some of the family history that has eluded her most of her life. During World War II, her grandmother was incarcerated in Gila River, and her grandfather was in Topaz. She’d never asked them about their experiences. They were among the more than 110,000 held in camps between 1942 and 1945 as a result of an executive order requiring the forced removal of Japanese-Americans to what the government referred to as “relocation centers.”

Sydney first learned about incarceration not through family stories, but in school.

“I came home from school asking my parents about it, and all I really found out was that my grandparents were children during the war and basically grew up in camp,” Sydney says. “My dad didn’t know much either, because my grandparents never spoke about it.”

Many descendants of camp survivors grew up without learning about the camps because their families never discussed it, whether out of embarrassment, shame, or painful memories associated with being imprisoned. Being detained in camps by the U.S. government interrupted thousands of lives. Japanese-American children were plucked from their schools, some right before they could graduate and earn their diplomas. Families lost their businesses and farms, and because people were allowed to bring only what they could carry with them to camp, they had to sell their furniture and belongings.

Japanese-Americans fared no better once in camp, where they were assigned identification tags that made them feel like cattle, and watchtowers loomed over them as they made their way to school or the mess hall. Because the camps were isolated from the rest of American society in deserts, swamps, and mountainous regions, they faced extreme weather conditions, from which their flimsy barracks failed to protect.

By standing outside in the heat at Manzanar, pilgrims like Sydney were able to get a small taste of what daily life was like for Japanese-Americans in camp.

The first official pilgrimage to Manzanar was organized in 1969 by a group of young Japanese-Americans who, like Sydney, were seeking to understand what had happened to their families during the war. They knew their families faced racism in their communities, which intensified after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, leading to the U.S. to enter WWII. They knew President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, violating the rights of thousands of American citizens. They knew the camps were shut down in 1945, and their families had to find housing and apply for jobs, rebuilding their lives all over again.

But the trauma their parents and grandparents endured, and what that meant for their children as well as the community’s future, were issues that lingered long after the camps closed. Prior to the war, at the turn of the century, there had been over 40 Japantowns in the United States, enclaves that celebrated and catered to the Japanese-American community. That number dwindled after 1945, partly due to the displacement of families who took the jobs they could find after camp.

Bruce Embrey, cochair of the Manzanar Committee, son of Sue Kunitomi Embrey, and one of the founding members of the pilgrimage, tells Teen Vogue the inaugural gathering was the first step of a long healing process for the Japanese-American community.

“The pilgrimage forced the community to come to grips with what happened, and to understand why Japanese-American community centers like Little Tokyo in Los Angeles were disrupted,” Bruce tells Teen Vogue. “It later empowered the community as a whole to seek redress. Without the pilgrimages, there wouldn’t be a venue, a way for the community to come together and think about it.”

In the late ’70s, the pilgrimage became a site for community activists to organize around the issue of redress for Japanese-Americans, which they achieved with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the pilgrimage was a safe space for the community to offer support to the Muslim community, which was being treated with the same kind of xenophobia many Japanese-Americans recognized well.

And in 2019, the pilgrimage evolved into a multicultural gathering, whose participants have called for solidarity with other targeted communities and condemned current events like the so-called “Muslim bans” and a proposed Muslim registry, as well as the separation and imprisonment of asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The 50th anniversary program featured several speakers, including Nihad Awad, the co-founder of the Council of American-Islamic Relations, who shared his memories of 9/11, saying “an attack on one community is an attack on all of us.” Warren Furutani, another pilgrimage cofounder, emceed the program. One of the keynote speakers was Karen Korematsu, founder of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute and daughter of Fred Korematsu, whose objection to being forced into camp led to the infamous court case that upheld the legality of incarceration.

“We have skin in the game; this is our history,” Karen tells Teen Vogue about the necessity of holding annual pilgrimages. “If we don’t take the time to continue to educate others and share this history, it’s going to disappear.”

Karen encouraged young attendees to exercise their right to vote, as well as to go home and ask their parents about their own family’s sacrifices because “once you know your own story, you can appreciate and support the stories of others.”

The program closed with a procession of banners, each representing one of the 10 camps. Sydney listened for the numbers of the imprisoned announced after Gila River and Topaz, silently recognizing her grandparents.

Now she wants to return home to Sacramento. Though her grandfather has passed away, Sydney says she feels an urgency to hear her grandmother’s story and a responsibility to preserve it and share it with others.

“I felt so trapped in those few hours I was at the site,” Sydney says. “I can’t imagine how much this confinement took away from these people’s lives, and from my grandparents’ lives. It makes it much more real when you’re there.”

Spread the word