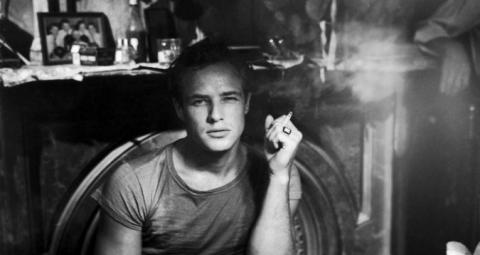

When Marlon Brando died in 2004 at 80, more than a few obituary writers decided he hadn’t been a contender, after all. For them, this brilliant actor had devolved into as much a loser as Terry Malloy, his punch-drunk boxer in “On the Waterfront,” who is sold down the river and, with a face battered by fights and the pain of a brother’s betrayal, famously eulogizes himself: “I coulda been a contender, I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am.” Those who dismissed Brando reviewed his life as if it were some kind of movie, one with a strong opening act, a bewildering middle and a disappointing conclusion deserving of a collective thumbs down.

That’s the straight world’s take on Brando — call it the revenge of the mediocre on genius — and one reason it’s such a blast to hear the man himself talking about that life in the documentary 'Listen to Me Marlon.' The movie is almost entirely narrated by Brando, largely through snippets of audio recordings that he made over decades. Although it opens with a bit of text about the recordings, it doesn’t explain how the British director Stevan Riley and his collaborators got their hands on them. The press notes state that the recordings were “uniquely gifted” to the production company for the movie; a recent article in The Los Angeles Times suggests a more commercially expedient reason: The actor’s estate, Brando Enterprises, “decided it was time” for a flick to introduce him to a new generation.

Whatever the motivations, the movie gives you the opportunity for its loquacious title subject to pour his thoughts into your ears for some 100 babbling minutes. This was a cat who could rap, as his longtime friend and former roommate James Baldwin might have said. The movie is stuffed with boldface names like Baldwin, who (with his pal Norman Mailer) first encountered Brando in Greenwich Village in the mid-1940s. “I had never met any white man like Marlon,” Baldwin later said. “He was obviously immensely talented — a real creative force — and totally unconventional and independent, a beautiful cat.” Baldwin said that Brando was “contemptuous of anyone who discriminated in any way,” adding that the actor, a professional seducer, made him feel that “reports I was ugly had been much exaggerated.”

There’s not enough of the nonconformist likes of Baldwin in the movie, but then it seems impossible to cram an existence as fully lived as Brando’s — which reaches from his Nebraska childhood to California, New York, Tahiti and beyond — into a few hours. That said, you get a sense of that life because, for a celebrity who became known as a recluse in his later years, Brando played the public relations game for a very long time, as the many interview clips show. Some of these are available online, including a 1955 “Person to Person” profile by Edward R. Murrow, which was shot soon after Brando won his first Oscar, for “On the Waterfront.” It’s a thoughtful interview, as far as these things go, and Brando plays along nicely, even when his abusive father, Marlon Sr., whom he loathed, bigfoots into view.

While its subject means that 'Listen to Me' is easy to like, Mr. Riley’s shaping of Brando’s words can make the movie, every so often, difficult to fully embrace. Mr. Riley’s handling of the fatal 1990 shooting of Dag Drollet by Christian Brando, Brando’s son, is especially unfortunate, and the use of some tabloidlike news material sleazes up the movie a touch. (Mr. Drollet was the boyfriend of Brando’s daughter Cheyenne.) Mr. Riley’s use of a disembodied, floating Brando head created from digital scans that the actor made in the 1980s is initially amusing, but it’s a needless distraction, as are the cutaways to murkily lit, messily appointed rooms that are actually re-creations of those in his Mulholland Drive mansion.

Brando doesn’t need that kind of embellishment, and neither does this movie. As his admirer James Dean probably knew all too well, Brando was a true rebel, partly because he thought being a star was absurd and partly because, as clip after clip shows, he always had a cause, whether it was civil rights, black power, Native American sovereignty or his own independence. At its most satisfying, 'Listen to Me Marlon' brings you close to a man whose legacy seems to have been tarnished less by his widely reported (and misreported) actions than by an entertainment press that punishes those who refuse to play the game. Brando found the game ludicrous. But he played along until he didn’t, and while he occasionally suffered the consequences, along with too many fools, his work outlasts it all.

'Listen to Me Marlon' opened this week in theaters around the country and will later be screened on Showtime.

[Manhola Dargis is currently a chief film critic for The New York Times, a position she shares with A. O. Scott. She was formerly a film critic for the Los Angeles Times, a film editor for the LA Weekly and has written for a variety of publications including Film Comment and Sight and Sound.Ms. Dargis grew up in Manhattan’s East Village, where she spent many happy hours watching movies at the long-lamented St. Mark’s Cinema and Theater 80. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband.}

Spread the word