Well, I was very much enjoying my holiday but COVID continues to do its COVID thing. It’s time for an update.

China: A humanitarian disaster

As expected, the COVID-19 situation in China is out of hand. In an interesting turn of events, China went from a “zero COVID” policy to a “let it rip” policy by dropping all mitigation measures without fully vaccinating the highest of risk or strengthening their healthcare system.

Egregiously, they stopped reporting cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, too. This looks good for them on paper, but when we rely on epidemiology 101 and anecdotal reports, which are plentiful, the situation in China is beyond grim.

Officials estimate between 5,000-10,000 people are dying per day. (At the U.S. peak, we lost 3,800 people per day). Epidemiologists expect death toll to rise in China in the coming months leading to 0.5-1 million cumulative deaths. A humanitarian disaster.

This outbreak could have implications worldwide, like the emergence of a variant of concern. The best we can tell, BF.7 is spreading in China, which is an Omicron subvariant about 3 evolutionary steps behind what is spreading in most of the world. But, a new variant of concern could appear. (This is more possible than probable because transmission is high everywhere).

Just like cases and deaths, though, China is not reporting genomic data. In other words, we don’t know if and how the virus is changing and what it may (or may not) mean to the international community.

U.S. responds domestically

So, how should the United States respond? Well, it depends on our goal: delay or decrease transmission from China? Identify variants of concern? Pressure the Chinese government to uphold international responsibilities?

Yesterday, the U.S. publicly signaled two goals:

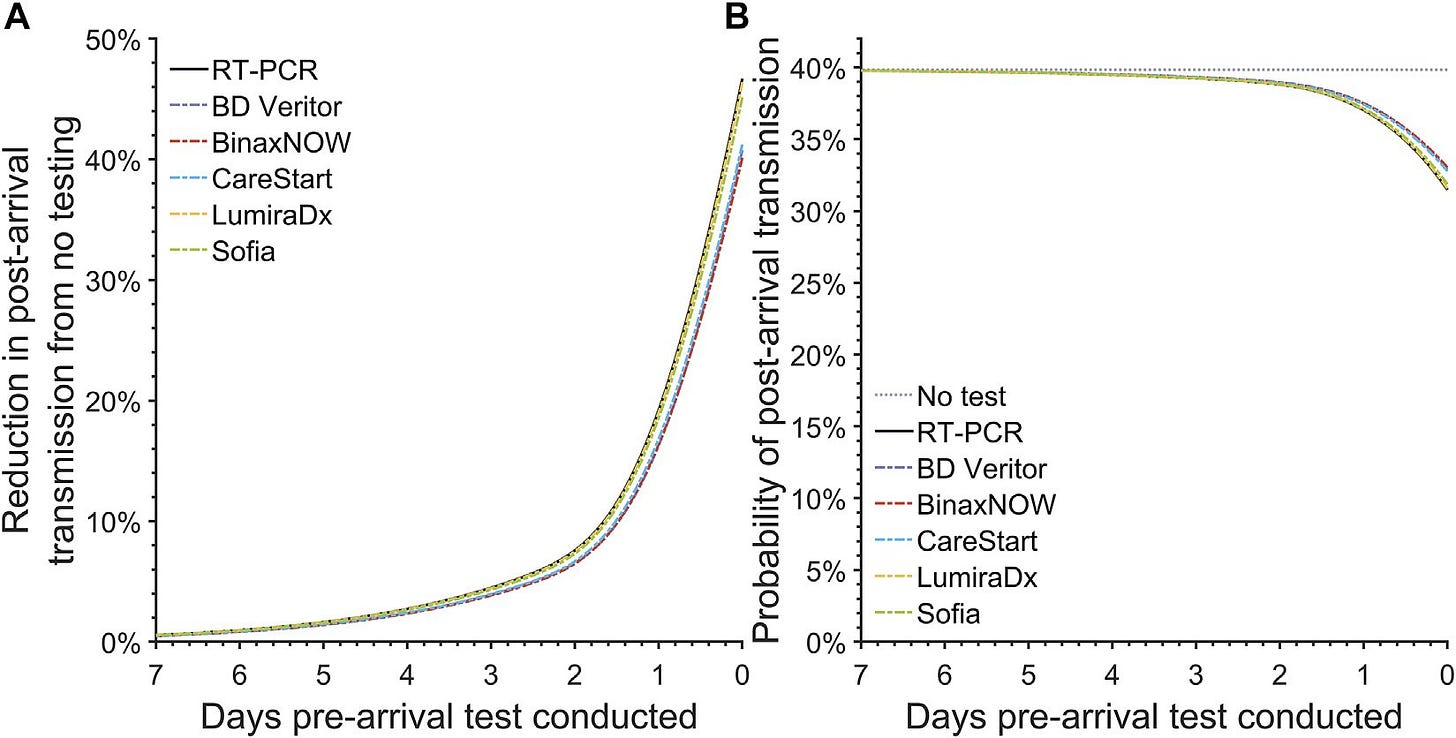

Delay transmission. On a scale from “do nothing” to “ban all travel”, the U.S. chose something in the middle. Travelers coming to the U.S. from China will be required to have a negative PCR test within 48 hours of departure. This starts on January 5, 2023. I assume the goal is to buy time—delay a wave in the U.S. seeded by travelers. And this may be a legitimate concern, as Milan reported that 50% of passengers on flights from China tested positive. However, the extent to which this delays transmission, and by how much, is up for debate:

Figure: The post-arrival transmission for pre-arrival testing. Wells et al., 2022. Int J Public Health. Source here.

-

As Adam Kucharski pointed out, “uncontrolled domestic transmission will grow exponentially while importations grow linearly. In other words, we’re much more likely to get an infection from a fellow resident than a traveler.”

-

The policy doesn’t start until next week in order for airlines to prepare, which likely won’t help if transmission is already out of control in China.

-

To test pre-departure within 48 hours of travel is problematic. Studies have shown that this will reduce transmission by only 10%.

-

Finally, buying time is only useful if we actually did something to prepare.

Using back of the napkin math, this policy would prevent ~10,000 infections in the U.S. If a variant of concern did pop up and was 100% immune invasive and every passenger had it (unlikely scenario), we would delay a wave by one week.

In any health crisis, policy decisions are challenging. Risks (ethics, lack of effectiveness, potential other harms, like xenophobia) must be weighed with benefits (low cost, possibility of delay). Then politics get involved. Epidemiologically this policy isn’t adding up for me.

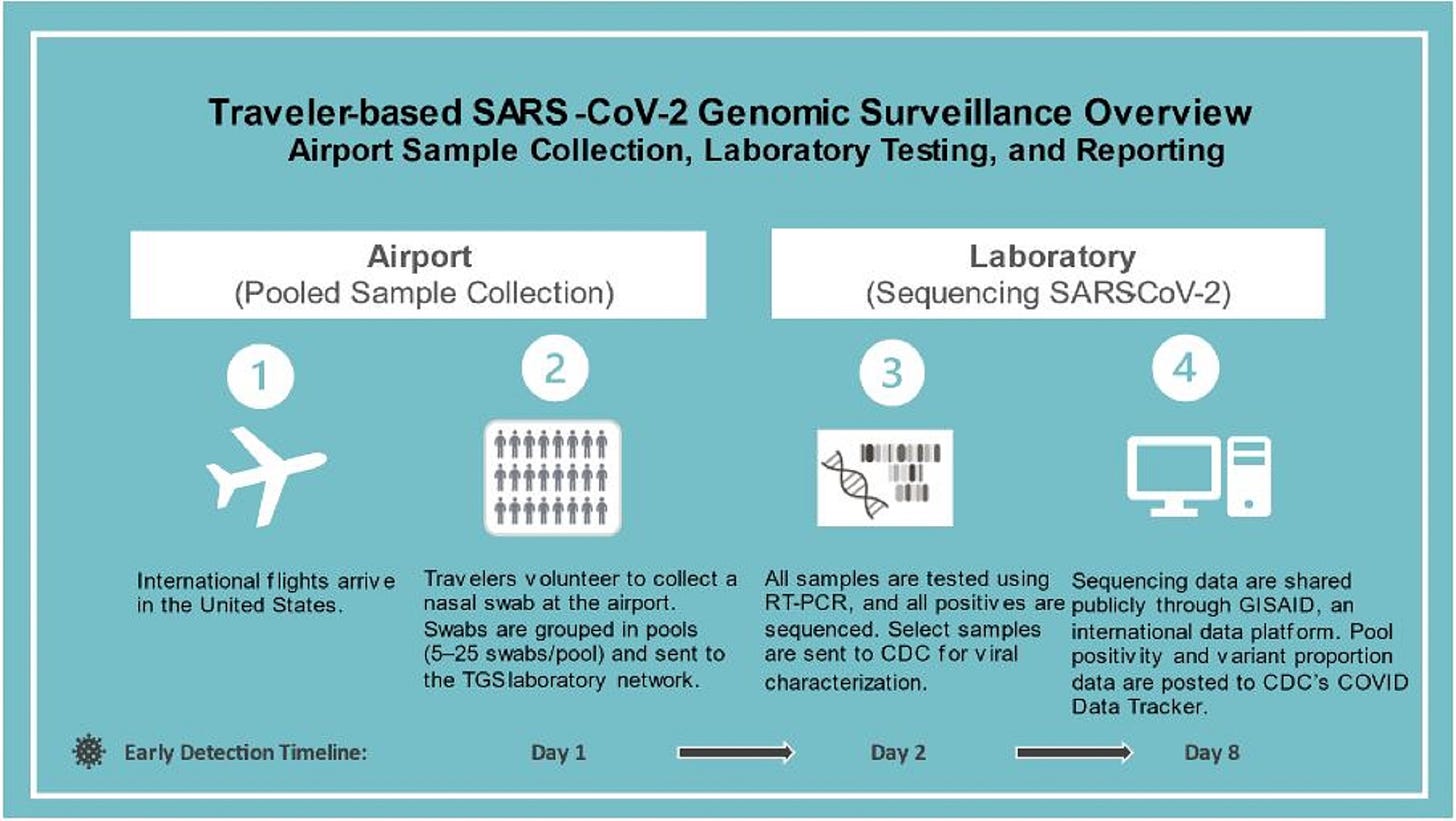

Find variants of concern. The second goal is to find potential variants of concern. Given zero data is being released by China, enhanced surveillance of PCR cases with a travel history to China is worthwhile. The U.S. will not have access to pre-departure testing results in China, but we can do it once people arrive.

The CDC already has a great program in place (see figure below), but because of the China situation, it expanded to 2 more airports. While this program is proactive, it’s not that big: 10% of passengers at 7 airports. We should expand our capacity even more. It would be more advantageous to sequence airplane wastewater.

(CDC)

A homegrown problem

Regardless of the China situation, current variants in the U.S. are likely more problematic. At least in the short-term.

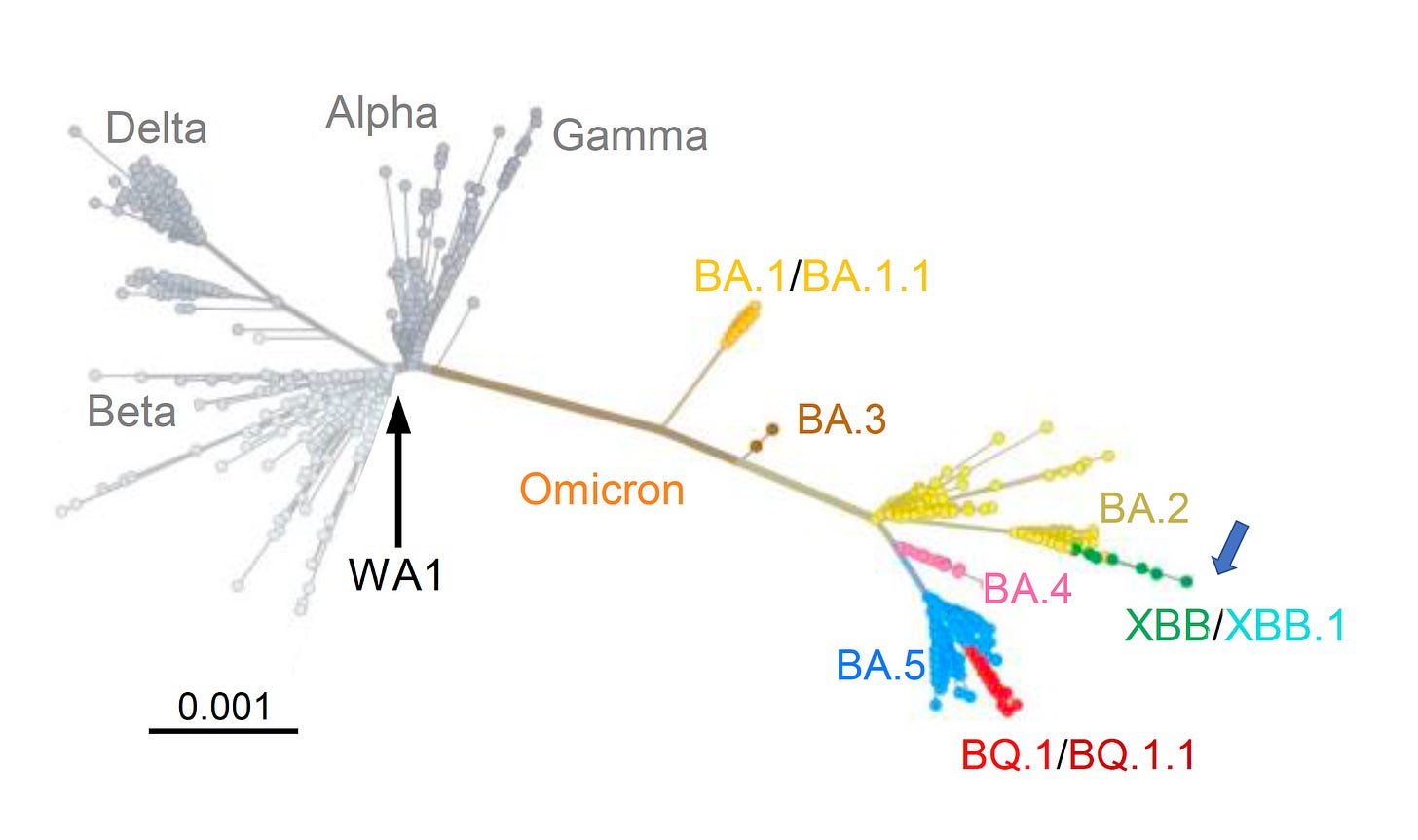

Specifically, we have a new subvariant on the horizon: XBB.1.5. This is an offshoot of BA.2, which is different from the subvariant currently circulating (BQ.1.1— an offshoot of BA.5).

Phylogenetic tree with scale bar indicating genetic distance, from Wang et al, Cell

Both lab and epidemiological data show XBB.5.1 may be cause for concern:

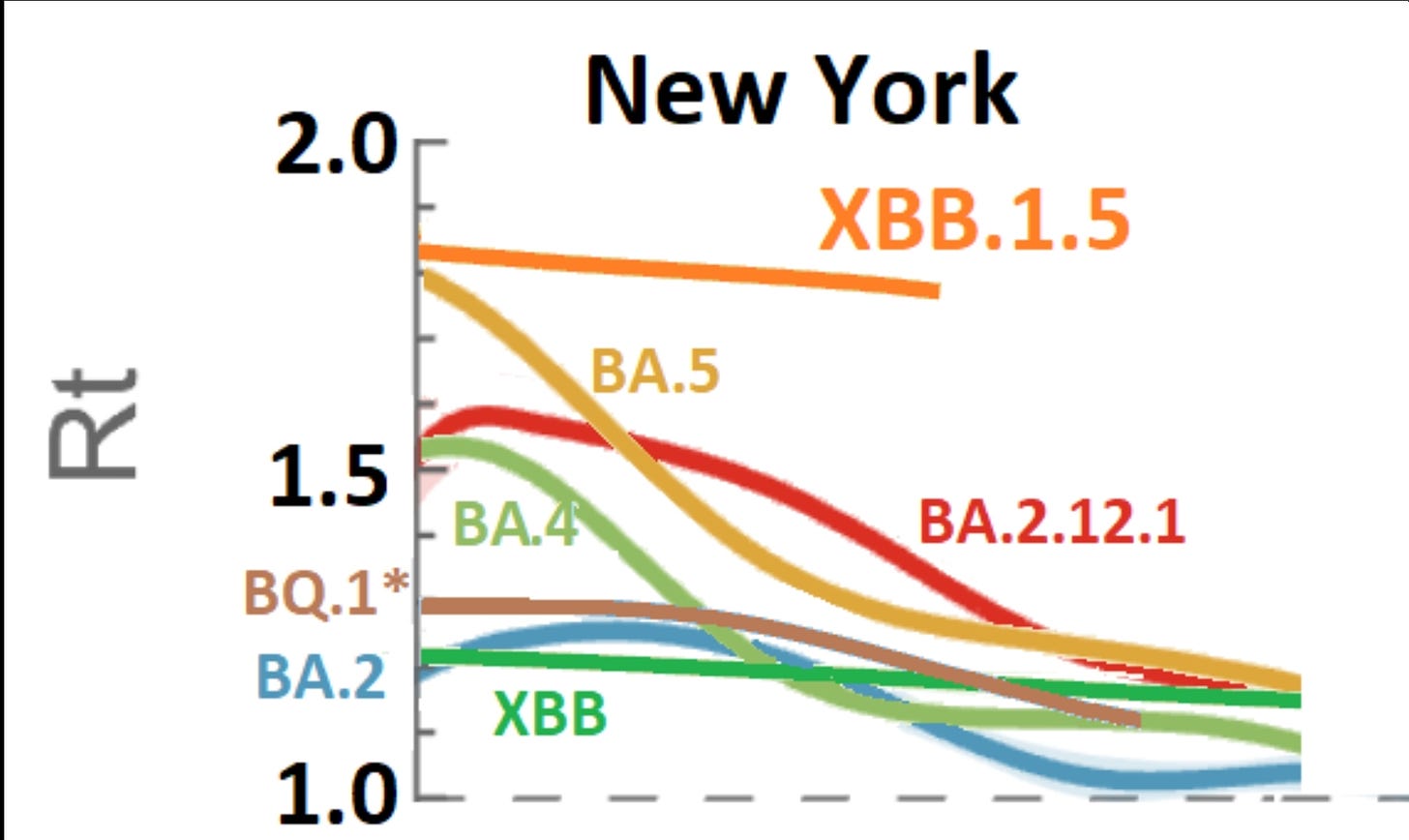

Source: Graph from JWeiland, Analysis from Trevor Bedford

-

In the “real world,” and particularly in New York, cases are exponentially increasing. Currently XBB.1.5 has a 120% weekly growth advantage, which equates to, on average, 1 infected person infecting 2 others. This rate is higher than we’ve seen with any other subvariant this year given our immunity wall.

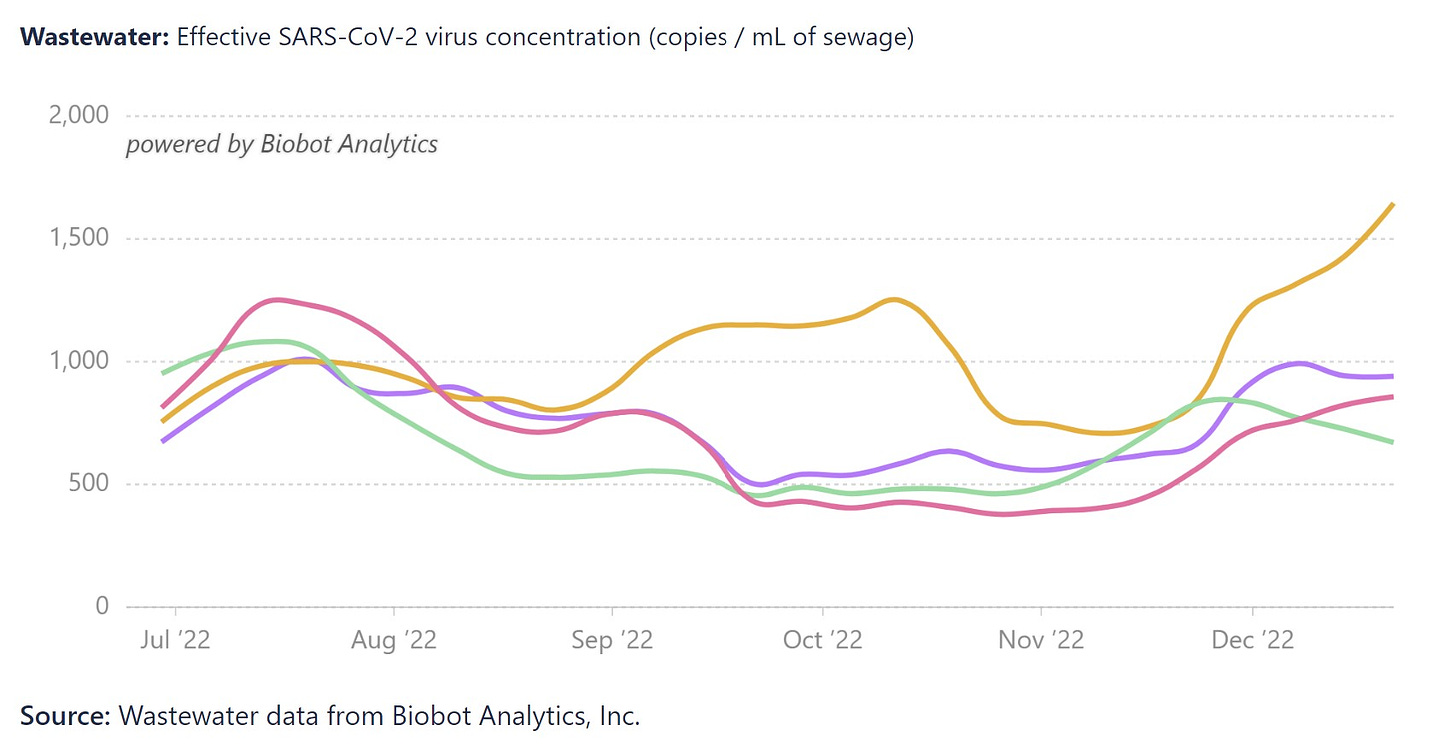

So, as expected, we see a clear uptick in Northeast wastewater. This is unwelcome given that admissions for people over age 70, for example, are the third highest since the pandemic began. This doesn’t reflect the new variant or impact of holidays, yet, either.

U.S. Covid-19 Wastewater Monitoring by Region. Yellow=Northeast; Pink= South; Green= West, Purple=Midwest (Source: Biobot Analytics)

-

In the lab, XBB.1.5 is presenting a more confusing picture. It has a similar ability to escape our immunity as other subvariants. Because of this, we wouldn’t think it would cause a massive wave compared to what is circulating right now. XBB.1.5 does have higher ACE2 binding affinity—it allows it to latch onto our cells better; it’s more sticky—but that wouldn’t necessarily cause it to be more transmissible. So something else may be going on—another part of the virus may have changed that influences transmission. We need to look into this more.

Bottom line

We should be very concerned for the people of China. And it is possible that a variant of concern will arise from their disaster. But the U.S. already has a problem of its own.

I was hoping for a quieter 2023. There may still be a chance, but these are not welcome developments going into the New Year.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe.

Spread the word