Why Asian Americans Don’t Vote Republican

During the recent No Labels-hosted Problem Solver Convention in New Hampshire, things got a little uncomfortable.

When Joseph Choe, an Asian-American college student, stood up to ask a question about South Korea, Donald Trump cut him off and wondered aloud: “Are you from South Korea?”

Choe responded, “I’m not. I was born in Texas, raised in Colorado.” His answer prompted laughter from the audience, and nothing more than a shrug from the GOP presidential candidate.

Media outlets like NPR and the Huffington Post mocked this interaction as a “Where are you from?” moment.

A fellow conference attendee who walked by Choe subsequently joked, “You’re gonna have to show him your birth certificate, man!”

Although Trump probably did not intend to offend, this interaction likely reminded Choe and other Asian-American voters that being Asian often translates to being perceived by fellow Americans as a foreigner.

However innocuous Trump’s question may seem, this is exactly the sort of exchange that could, in part, be pushing Asian Americans – the highest-income, most-educated, and fastest-growing segment of the United States – toward the Democratic Party by landslide margins.

A landslide for Obama

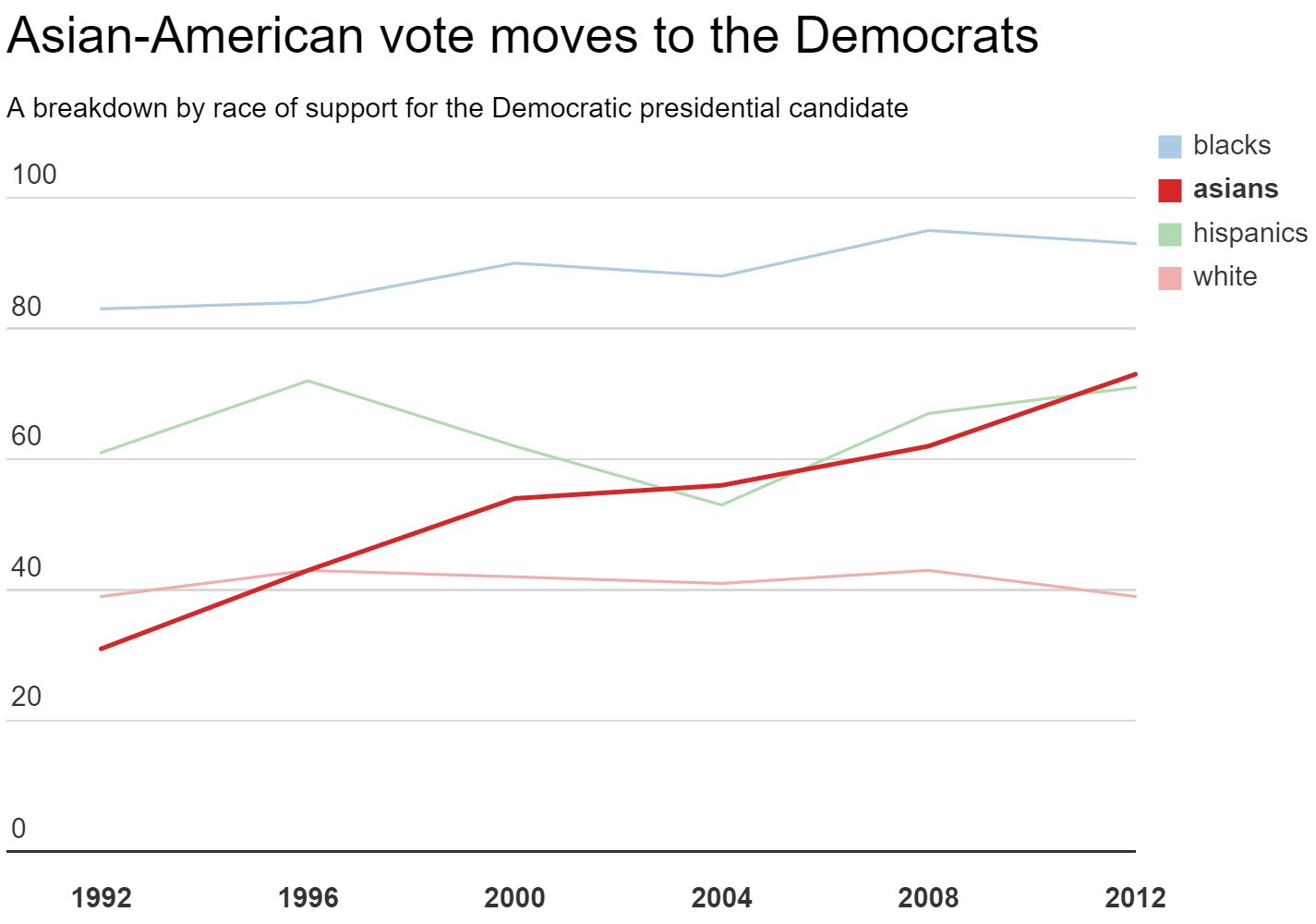

In the 2012 presidential election, Barack Obama won 73% of the Asian-American vote. That exceeded his support among traditional Democratic Party constituencies like Hispanics (71%) and women (55%).

Republicans should be alarmed by this statistic, as Asians weren’t always so far out of reach for Republicans.

When we examine presidential exit polls, we see that 74% of the Asian-American vote went to the Republican presidential candidate just two decades ago. The Democratic presidential vote share among Asian Americans has steadily increased from 36% in 1992, to 64% in the 2008 election to 73% in 2012. Asian Americans were also one of the rare groups that were more favorable to President Obama in the latter election.

Source: New York Times presidential election exit polls, 1992-2012 Get the data

This dramatic change in party preference is stunning. No other group has shifted so dramatically in their party identification within such a short time period. Some are calling it the “GOP’s Asian erosion.”

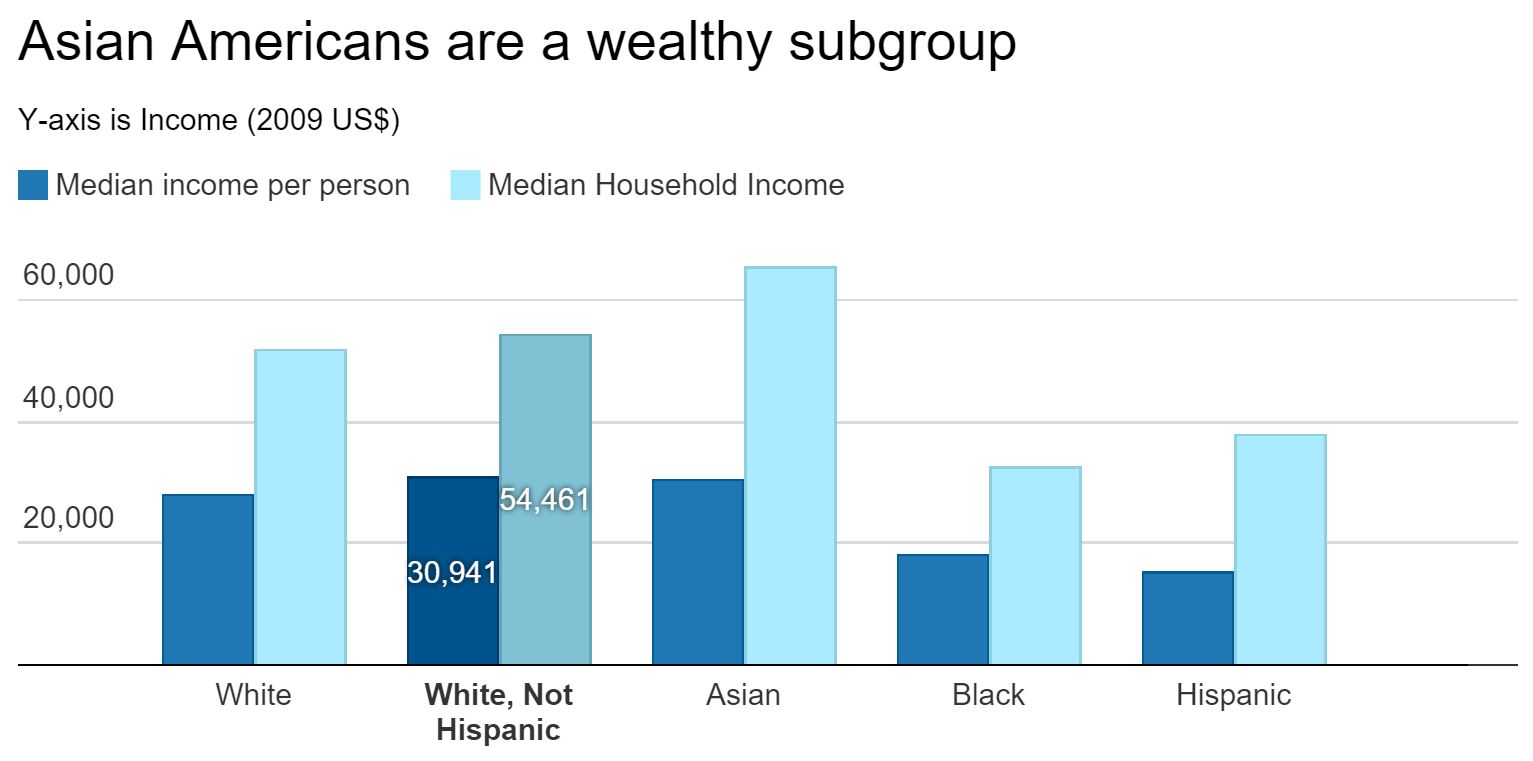

Moreover, Asian Americans as a group have a number of attributes that would usually predict an affinity for the Republican Party.

American Enterprise Institute’s notes:

If you’re looking for a natural Republican constituency, Asians should define ‘natural' … And yet something has happened to define conservatism in the minds of Asians as deeply unattractive.

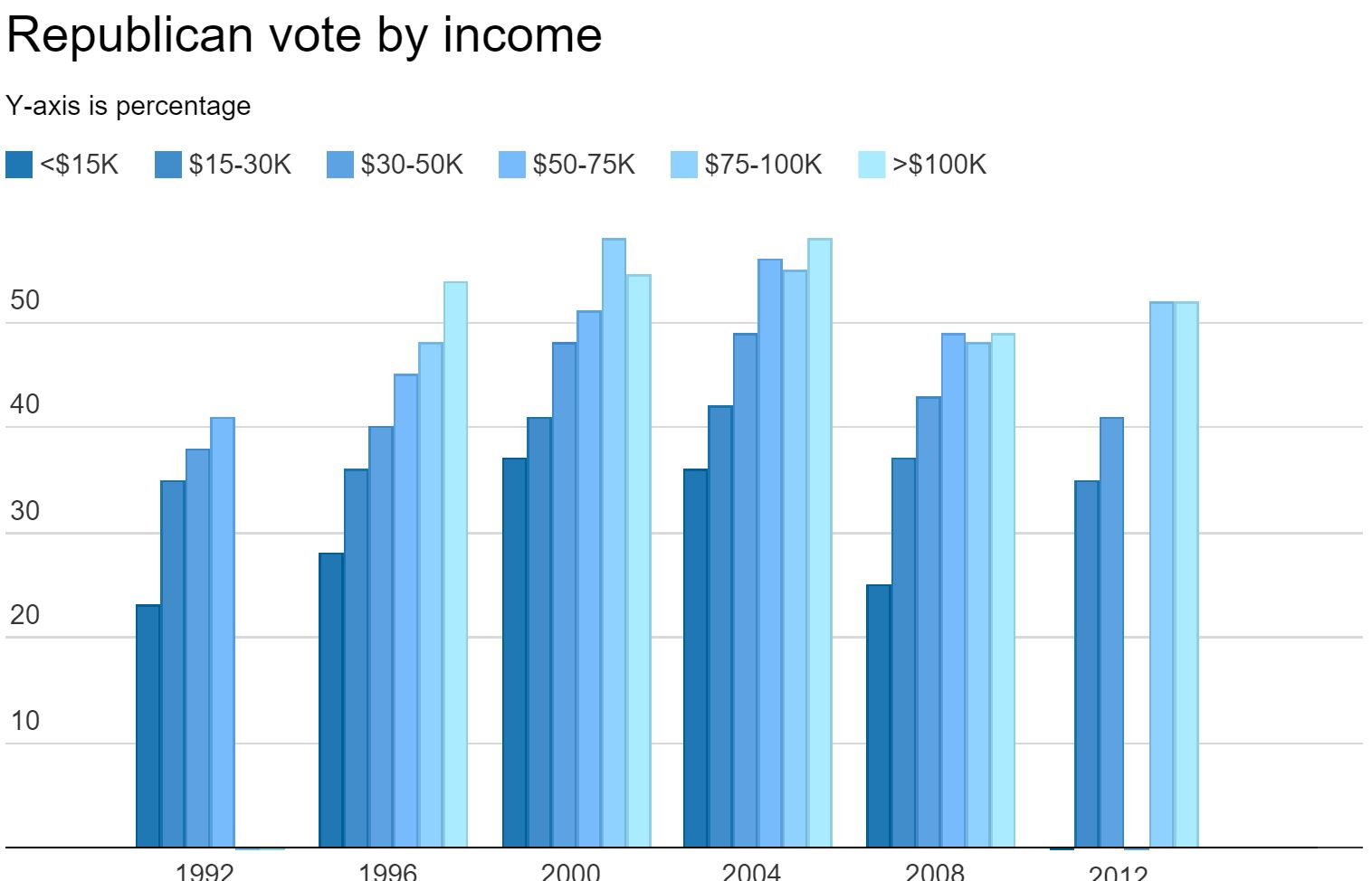

As shown by Andrew Gelman and his coauthors in their book Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State: Why Americans Vote the Way They Do, income is a powerful driver of political party preferences. Generally, richer voters are more likely to vote Republican.

Asian Americans' income is, on average, higher than any other ethnic group in the United States. According to the US Census Bureau, in 2009, the median Asian household had a higher income (US$65,469) than the median white household ($51,863). Median black and Hispanic household incomes were $32,584 and $38,039, respectively.

Source: New York Times presidential election exit polls, 1996-2012

So why are Asian Americans leaning left instead of right?

My research with Alexander Kuo and Neil Malhotra offers one explanation. The feeling of social exclusion stemming from their ethnic background might be pushing Asian Americans away from the Republican Party.

The hated question

Asian Americans are regularly made to feel like foreigners in their own country through “innocent” racial microaggressions. Microaggressions are “everyday insults, indignities and demeaning messages sent to people of color by well-intentioned white people who are unaware of the hidden messages being sent.” An example is being asked “Where are you really from?” – after answering the question “Where are you from?” with a location within the United States. Another is being complimented on one’s great English-speaking skills. In both cases, the underlying assumption is that Asian Americans are outsiders.

According to a 2005 study by Sapna Cheryan and Benoit Monin, Asian Americans are right to feel excluded. The study shows Asian Americans are seen as less American than other Americans.

A 2008 study by Thierry Devos and Debbie Ma confirmed this result. The study found that in the mind of the average American, a white European celebrity (Kate Winslet) is considered more American than an Asian-American celebrity (Lucy Liu).

But while Asian Americans are perceived as less American by other ethnic groups, Cheryan and Monin found that Asian Americans are just as likely as white Americans to self-identify as American and hold patriotic attitudes. This makes attacks on their identity as Americans hurtful.

The impact of racial microaggressions on exclusionary feelings can be magnified in political contexts, such as advertisements, political rhetoric, and policy positions on issues related to Asians like immigration.

How is this politically consequential?

We posit that rhetoric from Republicans insinuating that nonwhite “takers” are taking away from white “makers,” as well as their strong anti-immigrant positions, has cultivated a perception that the Republican Party is less welcoming of minorities. Since the Democratic Party is seen as less exclusionary, we find that triggering feelings of social exclusion makes Asian Americans favor Democrats.

We conducted an experiment in which Asian Americans were brought into a university laboratory. Half were randomly subjected to a seemingly benign racial microaggression like Trump’s clueless remarks to Choe before being asked to fill out a political survey. The white assistant was instructed to tell half of the study participants “I’m sorry. I forgot that this study is only for US citizens. Are you a US citizen? I cannot tell.”

Asian Americans who were exposed to this race-based presumption of “not belonging” were more likely to identify strongly as a Democrat. They were also more likely to view Republicans generally as close-minded and ignorant, less likely to represent people like them, and to have more negative feelings toward them.

Our finding is remarkable given that the racial microaggression was mentioned only once, and was of the most benign nature. Our experiment confirms that Asian Americans associate feelings of social exclusion based on their ethnic background with the Republican Party.

Social exclusion based on race is common

When we examined the 2008 National Asian American Survey (NAAS), a nationally representative sample of over 5,000 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, we found that self-reported racial discrimination, a proxy for feelings of social exclusion, was positively correlated with identification with the Democratic Party over the Republican Party.

Analyzing the NAAS data, we find that racial discrimination is not rare. Nearly 40% of Asian Americans suffered at least one of the following forms of racial discrimination in their lifetime:

- being unfairly denied a job or fired

- being unfairly denied a promotion at work

- being unfairly treated by the police

- being unfairly prevented from renting or buying a home

- treated unfairly at a restaurant or other place of service

- being a victim of a hate crime.

It is important to note that our findings do not mean that social exclusion is the only reason why Asian Americans are Democrats. However, they do provide some insight on why Asian Americans are leaning left today.

Significance of the Asian-American vote

Understanding Asian-American political behavior has important electoral ramifications. According to a 2013 US Census report, while Asian Americans are only 5% of the US population and about 4% of voters, in some states they make up a considerably higher proportion of the electorate. Asian Americans make of 12% of likely voters in California. They are projected to become 9% of the overall US population by 2015.

Since 1996, the number of Asian Americans who cast votes has increased by 105%, in contrast to a 13% increase among white voters. Additionally, while the lion share of Asian American votes are going to Democratic candidates, according to Zoltan Hajnal and Taeku Lee, the majority of Asian Americans are not officially affiliated with any party. That means they’re “gettable” by either party.

So what can the GOP do to win the Asian-American vote?

The short answer is, not what they are currently doing.

As long as Republicans appear unwelcoming of minorities, our findings suggest, they will struggle to get Asian Americans’ electoral support.

Recent rhetoric around immigration reform from leading Republican presidential candidates goes beyond subtle racial microaggressions. The current Republican candidates are being explicitly exclusionary. Donald Trump and Ben Carson are doubling down on anti-immigrant sentiments, stating sweeping and offensive stereotypes of immigrants.

Jeb Bush, rather than apologizing for the use of the offensive term “anchor babies,” defended the use of the term by redirecting the conversation away from Latino immigrants to Asian immigrants.

Our study suggests that the increasing salience of issues like immigration that implicitly or explicitly offend minority groups coupled with exclusionary rhetoric from prominent leaders of the Republican Party will continue to push Asian Americans to the Democratic Party.

Cecilia Hyunjung Mo is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Vanderbilt University