When America Was Overcome with Anti-Japanese Xenophobia During WWII, One Union Fought Back

In the aftermath of the devastating terrorist attacks in Paris, a new wave of fear and hatred directed against Arab and Muslim people has re-emerged in the United States. Given this turn of events, it seems wise to revisit U.S. history and its most infamous example of internment: that of more than 100,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans.

Then, too, anger and hate reached a fever-pitch that seemingly could not be tempered. But the leaders of one, radical labor union, International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), fought back.

Despite the fact that there is incredible diversity among the 1.5 billion Muslims in the world, some Americans still paint them all with the same brush. Most loudly, Donald Trump—currently leading the Republican field in the 2016 presidential race—called for a database of all Muslims in the United States so as to track their movements. Similarly, Ben Carson, another popular Republican candidate, compared Syrian refugees to “rabid dogs.”

This hysteria quickly morphed into some—including the majority of governors in states around the country—advocating against accepting any more Syrian refugees while others have ratcheted up the Islamaphobia, with some arguing that all Syrians or maybe all Muslims in the United States should be interned in prison camps. One U.S. Navy veteran recently suggested on her Twitter feed, "Dearborn, MI, has the highest Muslim population in the United Sates. Let's fuck that place up and send a message to ISIS." A politician in Tennessee, Glen Casada, cried out for his state’s National Guard to “round up” the few dozen Syrian refugees in the state and deport them.

Of course, this current frenzy is hardly the first time Americans have been stampeded into such wild suggestions.

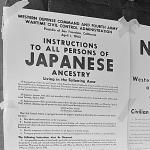

Internment in World War II

The December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, a vital base for the U.S. Pacific Fleet, enraged Americans. Many called for the blood of any and every Japanese person they could get their hands upon.

That Americans were shocked and enraged about the attack was understandable. But it also fed into the preexisting and virulent hatred of Japanese people among many other people in the United States. More than 30 years earlier, in 1907, this racism had resulted in a so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreement” between President Teddy Roosevelt and his Japanese counterpart to halt Japanese immigration to the United States. Moreover, existing Japanese immigrants were disallowed from becoming citizens (though children born on U.S. soil, of course, automatically were). (This discrimination closely followed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first time an entire ethnic group were categorically denied entry into the USA.)

Just over two months after the attack on Pearl, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which deemed all Japanese and Japanese Americans living near the Pacific Coast (where nearly all lived) a national security threat. FDR’s order led to approximately 110,000 people being relocated, against their will, to one of 10 internment camps in the interior West. These desolate prisons, most in sparsely populated desert areas, surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by U.S. soldiers, became the miserable homes for more than 100,000 people for the next three years. Not a single one of them had assisted in the Japanese strike at Pearl, nor committed any crime.

Nevertheless, the leader of the U.S. Army in the West, General John L. DeWitt, claimed at the time, “In the war in which we are now engaged, racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race.”

In other words, even though not a shred of evidence linked a single one of these Americans to espionage, their crime was being Japanese or an American of Japanese parents.

These Americans languished, miserable and downtrodden, for about three years in interment camps. The photographer Ansel Adams documented life in the camps, providing haunting photographs of the miseries of life there, which was something like being kept in prison for the crime of having Japanese ancestry.

The ILWU steps up

Who stood up on behalf of these innocent victims when hostility towards them reached epic proportions? Precious few—but among the most noteworthy was the ILWU.

In sworn testimony before Congress in February 1942, only three months after Pearl Harbor and prior to the implementation of FDR’s executive order, ILWU Secretary-Treasurer Louis “Lou” Goldblatt sagely predicted, “This entire episode of hysteria and mob chant against the native-born Japanese will form a dark page of American history. It may well appear as one of the victories one by the Axis powers.” He challenged the Congressmen, asking if “persecution of minorities rise in place of the standard of democracy?”

Why would Goldblatt and the ILWU fight on behalf of these Japanese Americans when almost no one else did? Simply put, they were radical unionists. Many were socialists and communists. Militant dockworkers had created their union in the depths of the Great Depression and committed it to total equality. In the hiring halls that they built, the member who had worked the least amount of hours in that portion of the year would get the first job dispatched, the “low man out” system.

The union’s policy—literally putting the ideal of equality into practice—was predicated upon the common sense, working-class notion of solidarity. It can be summed up in its motto “an injury to one is an injury to all,” first coined by an earlier, even more radical union, the Industrial Workers of the World (the "Wobblies").

Crucially, the ILWU commitment to equality included ethnic and racial equality, another legacy of the Wobblies.

ILWU President Harry Bridges, probably the most well-known left-wing labor leader in mid-20th century America, declared on more than one occasion, “If things reached a point where only two men were left on the waterfront,” if he had anything to say about it, “one would be a black man.”

The ILWU not only rhetorically condemned the internment program but also attacked the persecution of Japanese workers in its own ranks. Some Japanese and Japanese-American workers belonged to the ILWU including its Stockton, California warehouse division, a part of the San Francisco Bay Area Local 6.

In May 1945, the month Germany surrendered and three months before Japan would, the Stockton division denied a few Japanese-American members, recently released from an internment camp, reentry into the union. Rather than tolerate this discrimination, Bridges and Goldblatt pulled the charter until the white majority accepted the Japanese Americans back into the local. The whites soon caved, and Japanese-American workers were offered reentry.

Alas, the ILWU’s principled stands did not alleviate most Americans’ fear, hysteria or racism. One-hundred ten thousand totally innocent human beings were falsely imprisoned for about three years, ranking among the most shameful chapters in U.S. History.

The ILWU, race and social justice

Many people think of unions primarily for the benefits they bring their own members. But the ILWU engaged in what scholars call “civil rights unionism.” The ILWU and other unions like it advocated for causes beyond their members and workplaces. That was why, in 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited ILWU Local 10’s hiring hall in San Francisco to visit the longshoremen there.

Addressing a large gathering of dockworkers, King declared, “I don’t feel like a stranger here in the midst of the ILWU. We have been strengthened and energized by the support you have given to our struggles.” King continued, “We’ve learned from labor the meaning of power.”

More than 40 years later, the African-American longshoreman Cleophas Williams insightfully recalled to me King’s speech: “He talked about the economics of discrimination.” Williams had moved to the Bay Area during World War II to escape Jim Crow in his native Arkansas. He later became a leader in the ILWU. Williams also pointed out during our interview at his Oakland church that, “What said is what Bridges had been saying all along,” about how organized workers can materially benefit by attacking racism and forming interracial unions.

Unions' fight against xenophobia and for justice today

We live in scary times. In our quest for security, pre-existing prejudices easily can be exploited to horrific ends. Fortunately, knowing history provides us with examples of past mistakes as well as alternatives to problems today.

For instance, the interment of 110,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans now is widely condemned—outside of Roanoke, Virginia's mayoral office, at least—as having been a horrendous mistake, just as Lou Goldblatt predicted.

Goldblatt, Bridges and others in the ILWU stood up and spoke truth to power. They condemned the blatant prejudice that unfairly blamed all Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans for Pearl Harbor.

We often turn to history to learn what we got wrong, and there's plenty in U.S. history that falls into that category. But it can also teach us of what we got right, providing inspirational examples when brave people stood up to irrational witch hunts and denounced them for being bigoted and hysterical. ILWU history shows how people can actively combat racist hate by organizing across ethnic, national and racial boundaries.

In the neverending struggle for freedom and justice, unions remain among the largest and most powerful groups of non-elites. Even today, with membership down dramatically from their highs in mid-20th century, unions can play crucial roles in U.S. politics, helping their members earn living wages but also to fight for social justice. The ILWU, for one, strove to be anti-racist in an era when few majority-white organizations or white Americans were.

It would be a tragedy if Syrians, Arabs, and/or Muslims in the United States were rounded up and interned. Like the ILWU during World War II, we must swiftly and firmly condemn the absurd claims some Americans are making. Now, as in the past, we need organizations of working people to resist racism and xenophobia.

***

Peter Cole is a Professor of History at Western Illinois University. He is the author of Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive Era Philadelphia and is currently at work on a book entitled Dockworker Power: Struggles in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area. He is a Research Associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP) at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and has published extensively on labor history and politics. He tweets from @ProfPeterCole.