Poorest Areas Have Missed Out on Boons of Recovery

The gap between the richest and poorest American communities has widened since the Great Recession ended, and distressed areas are faring worse just as the recovery is gaining traction across much of the country.

These findings, outlined in a study to be released on Thursday by the Economic Innovation Group, a new nonprofit research and advocacy organization, may help explain why the country’s economic and political situation has become so polarized in recent years. The results, broken down into areas as small as individual ZIP codes, provide one of the most detailed looks at the nation’s growing inequality.

From 2010 to 2013, for example, employment in the most prosperous neighborhoods in the United States jumped by more than a fifth, according to the group’s analysis of Census Bureau data. But in bottom-ranked neighborhoods, the number of jobs fell sharply: One in 10 businesses closed down.

“It’s almost like you are looking at two different countries,” said Steve Glickman, executive director of the Economic Innovation Group, which created a new tool called the Distressed Communities Index.

The organization, based in Washington and founded last year with backing from several well-known technology entrepreneurs, includes economists on its advisory board from both the left and the right. Beyond its research functions, the group also supports greater private investment in struggling communities.

While the problems in many poorer cities predate the recession, what has felt like a real recovery for Americans in healthier cities and towns has left the worst-off locations — many of them concentrated in the nation’s old industrial heartland — even further behind.

“The most prosperous areas have enjoyed rocket-shiplike growth,” said John Lettieri, senior director for policy and strategy at the Economic Innovation Group. “There you are very unlikely to run into someone without a high school diploma, a person living below the poverty line or a vacant house. That is just not part of your experience.”

By contrast, in places the recovery has passed by, things look very different.

In the nation’s most distressed communities, the average house dates to 1959, 30 years older than the typical structure in the wealthiest ZIP codes. Population growth is flat or falling, not rising as it is in wealthier areas. More than half of adults don’t have a job, and nearly a quarter lack a high school diploma.

In the most prosperous ZIP codes, many of which are in the Sun Belt, only 6 percent of adults dropped out of high school and 65 percent are employed.

“They are enjoying a boom that camouflages what’s going on at the bottom,” Mr. Lettieri said.

Communities between these two extremes have managed only to tread water in recent years, the study found. Employment in communities in the median ZIP codes increased only slightly and the number of businesses did not grow at all.

Officially, the economy has grown every year since 2010, at an average annual rate of expansion of just over 2 percent. But don’t bother telling that to many Americans: A Fox News poll last year showed that 64 percent of people still thought the economy was in a recession, echoing an NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey in 2014 that found much the same thing.

Many experts have attributed this disconnect to stagnant wage growth for most workers, and a lower level of employment among prime-age Americans in recent years, especially for those who don’t have a college degree.

The new study suggests other factors are at work as well. In distressed areas, economic conditions continue to resemble those seen during a recession.

“ZIP codes mere miles apart occupy vastly different planes of community well-being — and few people are truly mobile between them,” the study concludes. “It is little surprise that many Americans feel they have been truly left behind.”

At the same time, the authors say, once a downward spiral begins, it is very difficult for residents or local political leaders to reverse the slide. “When businesses close and there is no investment, the tax base erodes,” Mr. Lettieri said. “Local governments can’t invest their way out.”

To come up with the rankings in the Distressed Communities Index, analysts focused on seven factors: the prevalence of adults with a high school degree, home vacancy rates, adults in the work force, the percentage of people living below the poverty line, median income as a percentage of the state average, change in employment and change in the number of businesses.

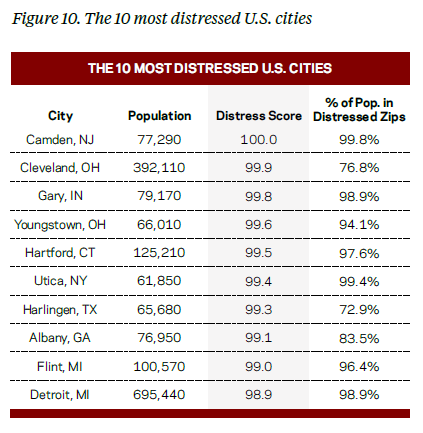

Many of the worst-off small and midsize cities on the index are synonymous with poverty, deindustrialization and other maladies affecting older urban areas. Camden, N.J.; Cleveland; Gary, Ind.; Youngstown, Ohio; and Hartford top the list.

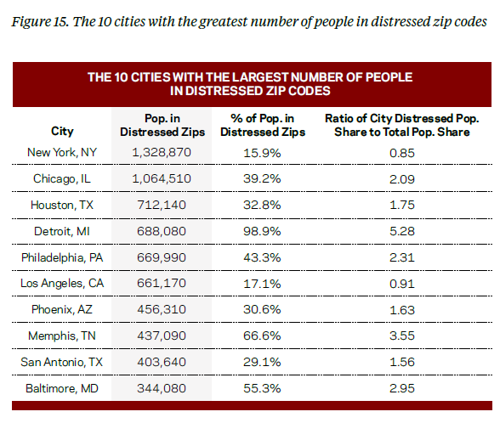

Over all, the South is home to more than half of the 50.4 million Americans living in distressed ZIP codes. It is also the only region in which more people live in distressed locations than in prosperous ones.

The most prosperous cities also tend to be among the newest and fastest-growing in the country, with a heavy concentration in the West. Five of the index’s most prosperous cities were in Texas, for example.

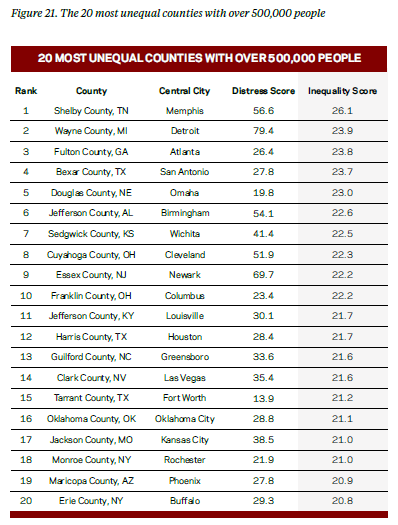

In some cities, especially those in the South and Southwest, booming newer areas coexist uneasily with poorer zones, creating what the Economic Innovation Group terms “spatial inequality.”

Even as suburbs of Dallas, Austin and Houston were thriving, Texas over all had more people living in distressed ZIP codes than any other state.

In San Antonio, ranked as the most spatially unequal city in the country, life in the northerly ZIP code 78258 has almost nothing in common with that of the ZIP code 78207, just west of downtown and the familiar Alamo Plaza.

In the poorer location, nearly half of adults did not have a high school diploma and 42 percent lived below the poverty line. Total employment and the number of businesses have both declined there.

Drive 30 minutes north on Route 281 to the wealthier ZIP code, however, and the poverty rate in 2014 was 4 percent. Only 2 percent of adults there lacked a high school diploma. Employment and the number of businesses jumped more than 20 percent since 2010.

Over all, the poorer San Antonio area scores a 97.8 on the Distressed Cities Index while the wealthier neighborhood’s reading is just 0.5.

In San Antonio, many of the surrounding suburbs are enjoying “explosive growth,” the report noted, but “it appears to be doing little to raise the fortunes of those living closer to the city center.”