Dirty Harry Lives

Patrick McGilligan’s biography of Clint Eastwood sets the actor’s changing fortunes against the backdrop of American politics. Issues of police brutality and right-wing vigilantism, in particular, dogged his career.

In the following extract, the iconic status of one of Eastwood’s most defining films, Dirty Harry, is attributed to a conservative longing for national confidence, power, and social order, all seemingly eroded by foreign military defeats and domestic civil rights and protest movements. Eastwood backed Nixon for the presidency shortly after the film’s release, thereby explicitly lending his star power to issues for which the Dirty Harry character stood as a perfect symbol.

Clint Eastwood said in later interviews that he had realized right from the outset of the project that Dirty Harry contradicted the 1966 Miranda v. Arizona decision of the US Supreme Court, which protected criminal suspects by assuring them they would receive a “Miranda warning” of their constitutional rights before police interrogation. This ruling was generally regarded as a victory for liberals and the bane of law-and-order conservatives.

Dirty Harry was a character who gladly bent the Miranda rules, and Clint’s dialogue excoriated mushy academics, stupid prosecutors and judges, inept government officials. Universal had offered the project to the more liberal actor, Paul Newman, at one point. Newman rejected it, citing his political qualms. “Well, I don’t have any political affiliations,” Clint had said to Jennings Lang, “so send it over.”

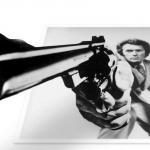

The film had pointed scenes that crossed the boundaries of decency and justice: jokes about Harry’s all-encompassing bigotry, Harry taking his arrest of Scorpio a little too far in the brutality department. The most notorious example was the scene in which Harry’s hot-dog lunch is interrupted by an ongoing bank robbery. Coolly and efficiently, Harry pulls his gun and breaks up the robbery, never mind car crashes and innocent bystanders darting for safety. Still munching on his hot dog, Harry approaches a bank robber sprawled on the pavement slowly inching towards his weapon. Harry points his pistol at this criminal suspect — an African American.

“I know what you’re thinking,” says Harry, rather matter-of-factly. “Did he fire six bullets or only five? Well, to tell you the truth, I kinda lost track myself. But seeing how the ’44 Magnum is the most powerful handgun in the world, and that it would blow your head clear off, you got to ask yourself — do I feel lucky today? Well, do ya, punk?”

The punk doesn’t feel lucky and he doesn’t go for his gun, but this scene, as even Clint said he realized, was a depth charge in the context of American politics. There was ample news coverage, in 1970–71, of cases where local and federal police had overstepped their authority by entrapment and obstruction of justice and even outright assassination. Often enough the criminal suspects (like the bank robber in Dirty Harry) were African American. Black Panther Party members went to court in Oakland, New Orleans, Chicago, New Haven, and New York City, and earned mistrials or acquittals.

If the police were being challenged on the streets and in the courts, the United States government was losing the Vietnam War. Clint himself said, in later interviews, that his Dirty Harry character helped quench people’s thirst for “vengeance,” which the actor linked to “a great feeling of impotence and guilt” over two national crises: Vietnam and Watergate, the scandal that drove President Nixon from office (albeit, Watergate did not occur until later, in 1972).

The cops, the government, the armed forces were losing. America needed a hero, a winner. In Dirty Harry, Clint not only found a contemporary persona to equal the Man With No Name, he also found one that seemed to embody a resurgent America. The line between actor and self, which Sergio Leone had maintained as a mystery quotient, appeared to dissolve.

The culminating — still provocative — sequences of Dirty Harry were the inspiration of Don Siegel: the school bus hijacked, Harry leaping from a bridge atop the bus, the bus crash, chase, and then ultimate face-off with Scorpio. The killer holds a Luger to the head of an innocent child. Harry shoots and manages to wound him. That is when Harry taunts Scorpio with the reprise of “Do ya feel lucky . . . ?” This time, when the criminal reaches for his gun, Harry fires first, finishing him off.

Clint said later, defensively, that he found a measure of resignation in that instant when Harry pulls the trigger, which defined for many people Dirty Harry’s simple-minded solutionism. If so, that internal sigh is all but invisible.

The scene had a telling postscript, which Siegel and Clint debated during the filming. After Scorpio’s execution, a disgusted Harry yanks off his badge and skips it into the water of a nearby sump. At first, Clint didn’t care for this conclusion. It was a cop-out. He didn’t play characters who were losers. Nor did he play “quitters.”

Siegel argued with him. “You’re not quitting. You’re rejecting the bureaucracy of the police department, which is characterized by adherence to fixed rules and a hierarchy of authority.”

EASTWOOD: I still feel I’m quitting by throwing away my badge.

SIEGEL: You’re wrong, Clint. You’re rejecting the stupidity of a system of administration, marked by officialdom and red tape.

Siegel came up with a compromise bit of action: “Harry draws his arm back as if to throw the badge into the sump. Suddenly, he pauses, as he hears the faint distant wail of approaching police sirens before the audience hears it. Then, with something close to a sigh, he puts the badge back in his pocket.” By the time they got around to shooting the coda of the story, however, the star had come around to agreeing with Siegel’s point of view. In the film, Dirty Harry does rip off his badge, quitting in disgust.

They might have left out Harry quitting if they had guessed that Dirty Harry was going to inspire such profitable sequels. Clint was already a golden goose, but while in production nobody seems to have realized that Dirty Harry was going to turn out to be as bountiful an egg as A Fistful of Dollars. But when it was released in December 1971, the film quickly shot to number one at the box office. Its eventual $53 million gross would almost triple the revenue of any of his previous American films and help make Clint, for the first time, in 1972, the top moneymaking star in Hollywood.

While some critics hailed Dirty Harry as a superior cop thriller (Jay Cocks in Time wrote that Clint gave “his best performance so far — tense, tough, full of implicit identification with his character”), others focused on the film’s veiled politique and decided that Clint flirted with a fascist message by ennobling a ruthless vigilante cop who expressed contempt for the courts and the legal bureaucracy.

Newsweek dubbed Dirty Harry “a right-wing fantasy.” A widely quoted freelance article in the Sunday New York Times, penned by a Harvard student, defined the film as glorifying “Nietzschean policemen” who were “without mercy.” Even Variety diagnosed the new Clint vehicle as “a specious, phony glorification of police and criminal brutality,” with “a superhero whose antics become almost satire.”

The review that gnawed the worst was Pauline Kael’s in the New Yorker. Kael described Dirty Harry as “a remarkably single-minded attack on liberal values, with each prejudicial detail in place.” She added: “When you’re making a picture with Clint Eastwood, you naturally want things to be simple, and the basic contest between good and evil is as simple as you can get. It makes this genre piece more archetypal than most movies, more primitive and dreamlike; fascist medievalism has a fairy-tale appeal.”

Kael had already proved a particular thorn in Clint’s side (she had taken on his spaghetti Westerns and denounced them as “stripped of cultural values”). As one of the most widely read and influential film essayists in America, Kael had many devoted readers and followers of her views. The term “fascist” stuck for a while.

“The long-term effects of her piece were slightly more ambivalent,” commented Richard Schickel in his authorized biography of Clint. “Interviewers kept asking him about it, and anyone attempting a critical overview of his career was obliged to conjure with it. Even now, when he is the beneficiary of one of the most astonishing reversals of critical fortune in movie history, a majority continues to hold with Kael. Yet it could be as well argued that this contempt has had a goading effect on Clint.”

Clint was hissed by feminists, a few times in the Bay Area. At the Oscar ceremonies that year, protesters outside carried signs reading “Dirty Harry Is A Rotten Pig.” Siegel and Clint didn’t like being labeled pigs or Nazis. They might have confessed to a film not entirely conscious of its hidden meanings; instead they insisted that Dirty Harry, consciously or otherwise, didn’t imply fascism of any sort.

The writer who wrote the film, and the director who orchestrated it, both were, ironically, liberal Democrats. They knew they were making “a pro-cop film,” in Dean Riesner’s words, but they didn’t overanalyze the implications. Nor did Clint. “Not once throughout Dirty Harry did Clint and I have a political discussion,” said Siegel.

Siegel, the true liberal, was particularly stung. As Dirty Harry was being released, his interviews would describe Harry as “a bitter bigot.” Later, the director would modify that, pointing out that he deliberately created a scene for Harry with an African American medical intern, and another one mocking the detective’s biases (with Harry ticking off his equal-opportunity detestation of limeys, micks, hebes, dagoes, niggers, hunkies and chinks). This, said Siegel, ought to tip people off that Harry was more “a tease” than a bigot.

Clint sometimes did seem bitter. “Jesus,” the man who played Dirty Harry told the Los Angeles Free Press in 1973, “some people are so politically oriented, when they see cornflakes in a bowl, they get some complex interpretation out of it.”

Clint’s oft-stated view was that Harry was obeying “a higher moral law.” “People even said I was a racist because I shot black bank robbers at the beginning of Dirty Harry,” he complained to New York City’s Village Voice in 1976. “Well, shit, blacks rob banks, too. This film gave four black stunt men work. Nobody talked about that.”

“So first I’m labeled right-wing. Then I’m a racist. Now it’s macho or male chauvinism. It’s a whole number nowadays to make people feel guilty on different levels. It doesn’t bother me because I know where the fuck I am on the planet and I don’t give a shit.”

Clint would probably accept “I don’t give a shit” inscribed on his tombstone. He liked to expound on “the rebel lying deep in my soul” and being “the outsider.” He preferred to be associated with Oakland, not Piedmont. Malpaso was a fiercely autonomous operation, according to publicity dogma; not an appendage of Universal or, later, Warner Brothers. As an actor who eschewed subtext, he couldn’t credit any unconscious urges in his persona. Clint’s entire image was anti-establishment. Imagine being labeled a Republican, a right-winger, even a latent fascist!

But after Nixon, Clint backed Ford, Reagan, both Bushes, and John McCain and Mitt Romney against Obama. Much of the rest of his career would align with Dirty Harry, from the four, increasingly bloodier Harry sequels to his flag-waving war movies to his old-man takedown of Hmong gangs in Gran Torino. The Chris Kyle biopic American Sniper, savaged by many as factually distorted and rightist, was the kind of film Clint might have starred in in his prime. Whatever else it was, ultimately American Sniper was a pro-gun statement from someone who has made that the hallmark of his career. Dirty Harry writ large: America’s gotta do what America’s gotta do.

His latest directed-only film is in the can: an uplifting biopic of Captain “Sully” Sullenberger, with Tom Hanks as the pilot who safely landed his passenger plane on the Hudson in 2009. At 85, like the energizer bunny, Clint keeps going and going.

No word yet which Republican tough guy he is for — Trump or Cruz. Dirty Harry may be torn.

Patrick McGilligan’s Clint: The Life and Legend is out now from OR Books.

The next issue of Jacobin, “Between the Risings,” is out this month. To celebrate its release, international subscriptions are $25 off.

Patrick McGilligan is the author of the proudly unauthorized biography of Clint Eastwood, Clint: The Life and Legend.