272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does It Owe Their Descendants?

WASHINGTON — The human cargo was loaded on ships at a bustling wharf in the nation’s capital, destined for the plantations of the Deep South. Some slaves pleaded for rosaries as they were rounded up, praying for deliverance.

But on this day, in the fall of 1838, no one was spared: not the 2-month-old baby and her mother, not the field hands, not the shoemaker and not Cornelius Hawkins, who was about 13 years old when he was forced onboard.

Their panic and desperation would be mostly forgotten for more than a century. But this was no ordinary slave sale. The enslaved African-Americans had belonged to the nation’s most prominent Jesuit priests. And they were sold, along with scores of others, to help secure the future of the premier Catholic institution of higher learning at the time, known today as Georgetown University.

Now, with racial protests roiling college campuses, an unusual collection of Georgetown professors, students, alumni and genealogists is trying to find out what happened to those 272 men, women and children. And they are confronting a particularly wrenching question: What, if anything, is owed to the descendants of slaves who were sold to help ensure the college’s survival?

More than a dozen universities — including Brown, Columbia, Harvard and the University of Virginia — have publicly recognized their ties to slavery and the slave trade. But the 1838 slave sale organized by the Jesuits, who founded and ran Georgetown, stands out for its sheer size, historians say.

At Georgetown, slavery and scholarship were inextricably linked. The college relied on Jesuit plantations in Maryland to help finance its operations, university officials say. (Slaves were often donated by prosperous parishioners.) And the 1838 sale — worth about $3.3 million in today’s dollars — was organized by two of Georgetown’s early presidents, both Jesuit priests.

Some of that money helped to pay off the debts of the struggling college.

“The university itself owes its existence to this history,” said Adam Rothman, a historian at Georgetown and a member of a university working group that is studying ways for the institution to acknowledge and try to make amends for its tangled roots in slavery.

Although the working group was established in August, it was student demonstrations at Georgetown in the fall that helped to galvanize alumni and gave new urgency to the administration’s efforts.

The students organized a protest and a sit-in, using the hashtag #GU272 for the slaves who were sold. In November, the university agreed to remove the names of the Rev. Thomas F. Mulledy and the Rev. William McSherry, the college presidents involved in the sale, from two campus buildings.

An alumnus, following the protest from afar, wondered if more needed to be done.

That alumnus, Richard J. Cellini, the chief executive of a technology company and a practicing Catholic, was troubled that neither the Jesuits nor university officials had tried to trace the lives of the enslaved African-Americans or compensate their progeny.

Mr. Cellini is an unlikely racial crusader. A white man, he admitted that he had never spent much time thinking about slavery or African-American history.

But he said he could not stop thinking about the slaves, whose names had been in Georgetown’s archives for decades.

“This is not a disembodied group of people, who are nameless and faceless,” said Mr. Cellini, 52, whose company, Briefcase Analytics, is based in Cambridge, Mass. “These are real people with real names and real descendants.”

Within two weeks, Mr. Cellini had set up a nonprofit, the Georgetown Memory Project, hired eight genealogists and raised more than $10,000 from fellow alumni to finance their research.

Dr. Rothman, the Georgetown historian, heard about Mr. Cellini’s efforts and let him know that he and several of his students were also tracing the slaves. Soon, the two men and their teams were working on parallel tracks.

What has emerged from their research, and that of other scholars, is a glimpse of an insular world dominated by priests who required their slaves to attend Mass for the sake of their salvation, but also whipped and sold some of them. The records describe runaways, harsh plantation conditions and the anguish voiced by some Jesuits over their participation in a system of forced servitude.

“A microcosm of the whole history of American slavery,” Dr. Rothman said.

The enslaved were grandmothers and grandfathers, carpenters and blacksmiths, pregnant women and anxious fathers, children and infants, who were fearful, bewildered and despairing as they saw their families and communities ripped apart by the sale of 1838.

The researchers have used archival records to follow their footsteps, from the Jesuit plantations in Maryland, to the docks of New Orleans, to three plantations west and south of Baton Rouge, La.

The hope was to eventually identify the slaves’ descendants. By the end of December, one of Mr. Cellini’s genealogists felt confident that she had found a strong test case: the family of the boy, Cornelius Hawkins.

Broken Promises

There are no surviving images of Cornelius, no letters or journals that offer a look into his last hours on a Jesuit plantation in Maryland.

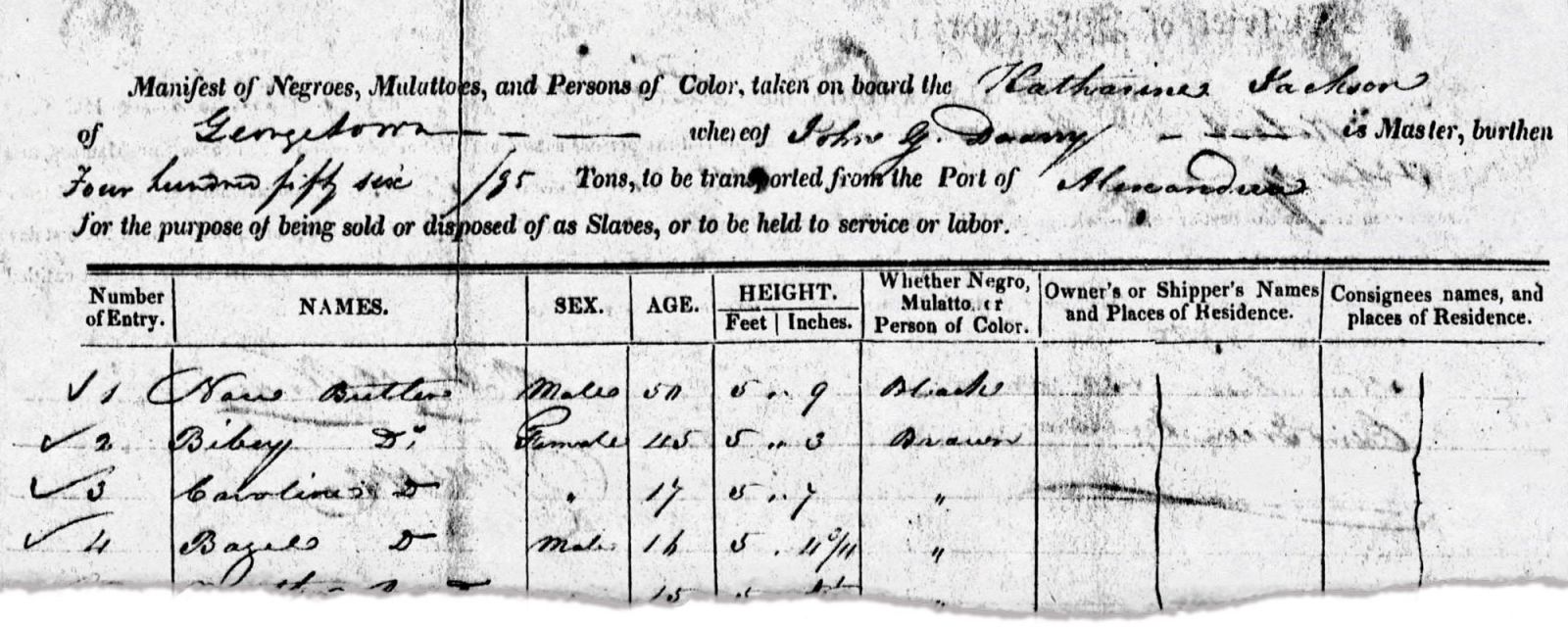

He was not yet five feet tall when he sailed onboard the Katharine Jackson, one of several vessels that carried the slaves to the port of New Orleans.

An inspector scrutinized the cargo on Dec. 6, 1838. “Examined and found correct,” he wrote of Cornelius and the 129 other people he found on the ship.

The notation betrayed no hint of the turmoil on board. But priests at the Jesuit plantations recounted the panic and fear they witnessed when the slaves departed.

Some children were sold without their parents, records show, and slaves were “dragged off by force to the ship,” the Rev. Thomas Lilly reported. Others, including two of Cornelius’s uncles, ran away before they could be captured.

But few were lucky enough to escape. The Rev. Peter Havermans wrote of an elderly woman who fell to her knees, begging to know what she had done to deserve such a fate, according to Robert Emmett Curran, a retired Georgetown historian who described eyewitness accounts of the sale in his research. Cornelius’s extended family was split, with his aunt Nelly and her daughters shipped to one plantation, and his uncle James and his wife and children sent to another, records show.

At the time, the Catholic Church did not view slaveholding as immoral, said the Rev. Thomas R. Murphy, a historian at Seattle University who has written a book about the Jesuits and slavery.

The Jesuits had sold off individual slaves before. As early as the 1780s, Dr. Rothman found, they openly discussed the need to cull their stock of human beings.

But the decision to sell virtually all of their enslaved African-Americans in the 1830s left some priests deeply troubled.

They worried that new owners might not allow the slaves to practice their Catholic faith. They also knew that life on plantations in the Deep South was notoriously brutal, and feared that families might end up being separated and resold.

“It would be better to suffer financial disaster than suffer the loss of our souls with the sale of the slaves,” wrote the Rev. Jan Roothaan, who headed the Jesuits’ international organization from Rome and was initially reluctant to authorize the sale.

But he was persuaded to reconsider by several prominent Jesuits, including Father Mulledy, then the influential president of Georgetown who had overseen its expansion, and Father McSherry, who was in charge of the Jesuits’ Maryland mission. (The two men would swap positions by 1838.)

Mismanaged and inefficient, the Maryland plantations no longer offered a reliable source of income for Georgetown College, which had been founded in 1789. It would not survive, Father Mulledy feared, without an influx of cash.

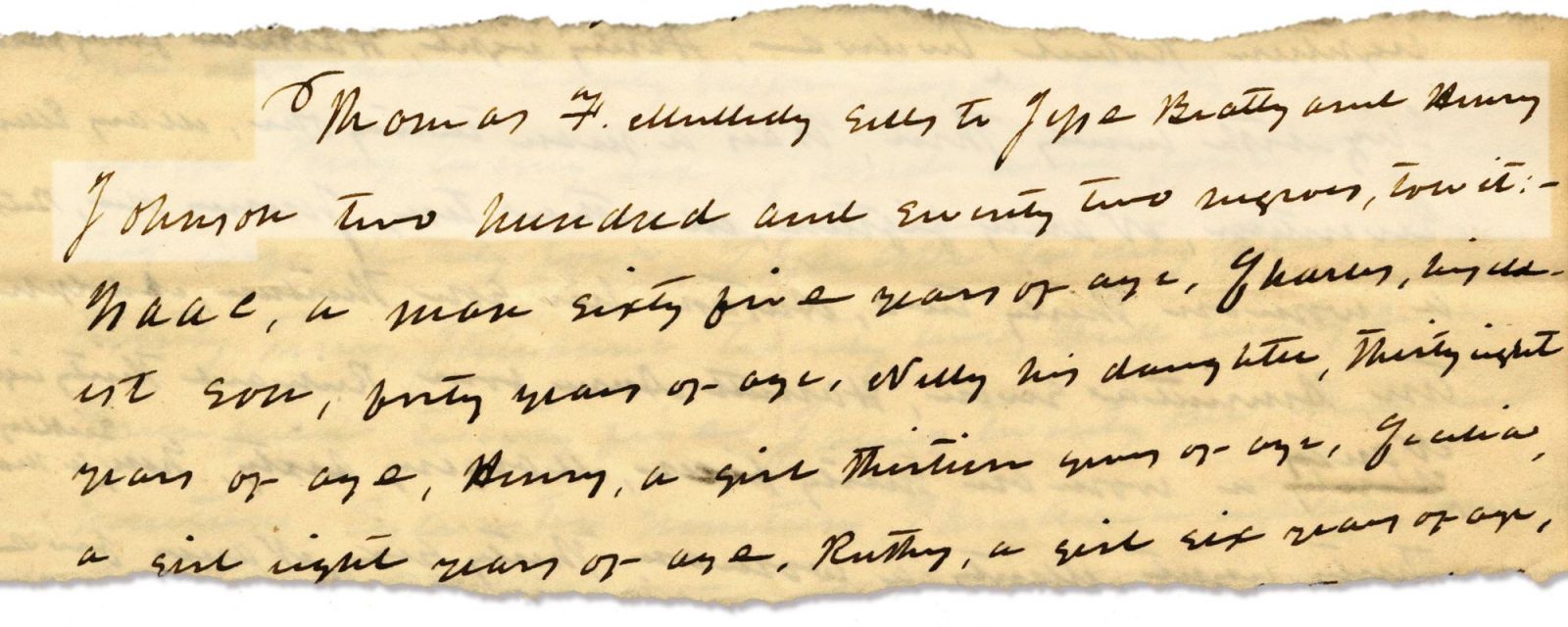

So in June 1838, he negotiated a deal with Henry Johnson, a member of the House of Representatives, and Jesse Batey, a landowner in Louisiana, to sell Cornelius and the others.

Father Mulledy promised his superiors that the slaves would continue to practice their religion. Families would not be separated. And the money raised by the sale would not be used to pay off debt or for operating expenses.

None of those conditions were met, university officials said.

Father Mulledy took most of the down payment he received from the sale — about $500,000 in today’s dollars — and used it to help pay off the debts that Georgetown had incurred under his leadership.

In the uproar that followed, he was called to Rome and reassigned.

The next year, Pope Gregory XVI explicitly barred Catholics from engaging in “this traffic in Blacks … no matter what pretext or excuse.”

But the pope’s order, which did not explicitly address slave ownership or private sales like the one organized by the Jesuits, offered scant comfort to Cornelius and the other slaves.

By the 1840s, word was trickling back to Washington that the slaves’ new owners had broken their promises. Some slaves suffered at the hands of a cruel overseer.

Roughly two-thirds of the Jesuits’ former slaves — including Cornelius and his family — had been shipped to two plantations so distant from churches that “they never see a Catholic priest,” the Rev. James Van de Velde, a Jesuit who visited Louisiana, wrote in a letter in 1848.

Father Van de Velde begged Jesuit leaders to send money for the construction of a church that would “provide for the salvation of those poor people, who are now utterly neglected.”

He addressed his concerns to Father Mulledy, who three years earlier had returned to his post as president of Georgetown.

There is no indication that he received any response.

A Familiar Name

African-Americans are often a fleeting presence in the documents of the 1800s. Enslaved, marginalized and forced into illiteracy by laws that prohibited them from learning to read and write, many seem like ghosts who pass through this world without leaving a trace.

After the sale, Cornelius vanishes from the public record until 1851 when his trail finally picks back up on a cotton plantation near Maringouin, La.

His owner, Mr. Batey, had died, and Cornelius appeared on the plantation’s inventory, which included 27 mules and horses, 32 hogs, two ox carts and scores of other slaves. He was valued at $900. (“Valuable Plantation and Negroes for Sale,” read one newspaper advertisement in 1852.)

The plantation would be sold again and again and again, records show, but Cornelius’s family remained intact. In 1870, he appeared in the census for the first time. He was about 48 then, a father, a husband, a farm laborer and, finally, a free man.

He might have disappeared from view again for a time, save for something few could have counted on: his deep, abiding faith. It was his Catholicism, born on the Jesuit plantations of his childhood, that would provide researchers with a road map to his descendants.

Cornelius had originally been shipped to a plantation so far from a church that he had married in a civil ceremony. But six years after he appeared in the census, and about three decades after the birth of his first child, he renewed his wedding vows with the blessing of a priest.

His children and grandchildren also embraced the Catholic church. So Judy Riffel, one of the genealogists hired by Mr. Cellini, began following a chain of weddings and births, baptisms and burials. The church records helped lead to a 69-year-old woman in Baton Rouge named Maxine Crump.

Ms. Crump, a retired television news anchor, was driving to Maringouin, her hometown, in early February when her cellphone rang. Mr. Cellini was on the line.

She listened, stunned, as he told her about her great-great-grandfather, Cornelius Hawkins, who had labored on a plantation just a few miles from where she grew up.

She found out about the Jesuits and Georgetown and the sea voyage to Louisiana. And she learned that Cornelius had worked the soil of a 2,800-acre estate that straddled the Bayou Maringouin.

All of this was new to Ms. Crump, except for the name Cornelius — or Neely, as Cornelius was known.

The name had been passed down from generation to generation in her family. Her great-uncle had the name, as did one of her cousins. Now, for the first time, Ms. Crump understood its origins.

“Oh my God,” she said. “Oh my God.”

Ms. Crump is a familiar figure in Baton Rouge. She was the city’s first black woman television anchor. She runs a nonprofit, Dialogue on Race Louisiana, that offers educational programs on institutional racism and ways to combat it.

She prides herself on being unflappable. But the revelations about her lineage — and the church she grew up in — have unleashed a swirl of emotions.

She is outraged that the church’s leaders sanctioned the buying and selling of slaves, and that Georgetown profited from the sale of her ancestors. She feels great sadness as she envisions Cornelius as a young boy, torn from everything he knew.

‘Now They Are Real to Me’

Mr. Cellini, whose genealogists have already traced more than 200 of the slaves from Maryland to Louisiana, believes there may be thousands of living descendants. He has contacted a few, including Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, president of the Eastern Washington Genealogical Society in Spokane, who is helping to track the Jesuit slaves with her group. (Ms. Bayonne-Johnson discovered her connection through an earlier effort by the university to publish records online about the Jesuit plantations.)

Meanwhile, Georgetown’s working group has been weighing whether the university should apologize for profiting from slave labor, create a memorial to those enslaved and provide scholarships for their descendants, among other possibilities, said Dr. Rothman, the historian.

“It’s hard to know what could possibly reconcile a history like this,” he said. “What can you do to make amends?”

Ms. Crump, 69, has been asking herself that question, too. She does not put much stock in what she describes as “casual institutional apologies.” But she would like to see a scholarship program that would bring the slaves’ descendants to Georgetown as students.

And she would like to see Cornelius’s name, and those of his parents and children, inscribed on a memorial on campus.

Her ancestors, once amorphous and invisible, are finally taking shape in her mind. There is joy in that, she said, exhilaration even.

“Now they are real to me,” she said, “more real every day.”

She still wants to know more about Cornelius’s beginnings, and about his life as a free man. But when Ms. Riffel, the genealogist, told her where she thought he was buried, Ms. Crump knew exactly where to go.

The two women drove on the narrow roads that line the green, rippling sugar cane fields in Iberville Parish. There was no need for a map. They were heading to the only Catholic cemetery in Maringouin.

They found the last physical marker of Cornelius’s journey at the Immaculate Heart of Mary cemetery, where Ms. Crump’s father, grandmother and great-grandfather are also buried.

The worn gravestone had toppled, but the wording was plain: “Neely Hawkins Died April 16, 1902.”