Harriet Tubman Is Perfect for the $20 Bill, But Which Tubman?

So now that it’s confirmed that Harriet Tubman will grace the front of the $20 bill, the next question is: Which Tubman? The antebellum abolitionist who supported John Brown and criticized Lincoln for his incrementalist approach to abolishing slavery, or the post-war figure of legend who was the subject of sentimental biographies?

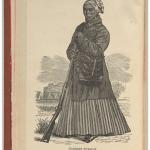

Designs for the new bill haven’t been released, and it could be well into the next decade for the newly designed currency to begin circulating. But the Bureau of Engraving and Printing will have some interesting choices when it comes to representing Tubman. The iconography of Tubman imagery generally falls into two categories: The best-known, and perhaps best-loved, images depict her as a little old lady, after the war, primly dressed and often sporting a head wrap. But while Tubman may have looked grandmotherly, she also was a ferociously brave and determined woman, and was occasionally depicted as such.

Typical of the first sort of image is a photograph made around 1885 by H. Seymour Squyer, showing Tubman full length in a dark dress wearing what was probably a colorful cloth on her head. But when the National Portrait Gallery featured an image of Tubman in a 2013 exhibition devoted to African Americans and the Civil War, they used another reproduction of a Tubman image, showing her dressed not for a Victorian photography studio, but in her outdoors garb, holding a gun.

Taken from a book about Tubman, this was a shockingly confrontational image. Although Tubman served in the U.S. Army during the war, and even led an armed raid that freed hundreds of slaves, the inclusion of a gun in a 19th-century image of an African American woman was startling. It also reminded readers that the acts for which Tubman is most celebrated—missions into Southern states to rescue slaves from bondage—were illegal, though obviously not immoral. After the infamous 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, even her own rescued relatives ran the risk of being returned to slavery. Tubman wasn’t working within the system; she saw clearly that the system couldn’t be reformed or repaired, only broken and replaced.

After the war, Tubman turned her formidable energies to the care of her family and the championing of women’s suffrage. As she aged, she seemed to soften in appearance. She was plagued by ill health and pain from a childhood injury (at the hands of a slave owner) though she lived well into her 90s. Photographs made late in her life show her diminished, and tired, as one might expect. But they also have the effect of softening the broader memory of who she was, and how she accomplished her heroic legacy. Popular books about her also lapsed into anodyne hagiography.

She was a fighter, and impatient for the freedom of her people and the suffrage of her sex; she repeatedly put her life on the line for what she believed in. And one hopes that’s how she appears on the $20 bill.

Philip Kennicott is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Art and Architecture Critic of The Washington Post. He has been on staff at the Post since 1999, first as Classical Music Critic, then as Culture Critic. Follow @PhilipKennicott