Finally, Campaign Finance Reform Gets Some Political Respect

On Tuesday, Maryland State Senator Jamie Raskin, a progressive Democrat, won his party’s nomination for an open congressional seat, despite being vastly outspent by two opponents. According to the latest figures compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, beverage mogul David Trone spent $9 million of his own money on the race and former local TV anchor Kathleen Matthews (wife of MSNBC talk show host Chris Matthews) spent $2.1 million, compared to $1.2 million for Raskin. His winning slogan: “An election is not an auction.”

Even more head-snapping: Over the weekend, a Republican candidate in Florida, arguably the quintessential political battleground state, seized on campaign finance reform as a way to stand out in a crowded race for the US Senate seat left open by Marco Rubio’s departure.

Rep. David Jolly (R-FL), a two-term lawmaker whose Gulf Coast district includes parts of St. Petersburg, has been riding a wave of publicity after giving an interview to CBS’ 60 Minutes in which he accused lawmakers of turning into “telemarketers,” and touted his plan to stop members of Congress from dialing for dollars. Earlier this year, Jolly introduced a bill that would ban federal officeholders from soliciting political donations. A striking sign of how the political winds are blowing: One of the Democratic candidates for the same Senate seat Jolly is seeking has signed onto the effort.

For campaign finance reformers, the good news is that ambitious politicians have now recognized their cause as a vote getter. “What Jolly told me is that it’s his one guaranteed applause line,” said Nick Penniman of IssueOne, a group that’s trying to build a bipartisan coalition to restrict the influence of money in politics.

It’s certainly not the only sign of gathering momentum for an issue that Washington insiders have long dismissed. Presidential candidates running the ideological gamut from Donald Trump to Bernie Sanders have made an issue of campaign finance reform on the stump. Earlier this month, more than 1,200 demonstrators got arrested in Capitol sit-ins demanding less money in politics and more access to the ballot.

“What the public has finally done in this election is connect the role that money plays in Washington with the impact on their own interests,” said Fred Wertheimer, the dean of Washington’s campaign finance advocates (he’s been active on the issue since before Watergate). “That is a breakthrough.”

Still, he’s not popping the champagne quite yet. “Grabbing onto the issue is one thing,” Wertheimer cautioned. “Willingness to support the kind of reforms necessary to fix the system is another.”

The difficulty in translating the political rhetoric about money in politics into political problem-solving boils down to differences in strategy. As Penniman describes it, some reformers believe in putting “points on the board in small measures.” Others, meanwhile, think “you’ll only get one bite at the apple” and so want to hold out for a measure that’s sweeping.

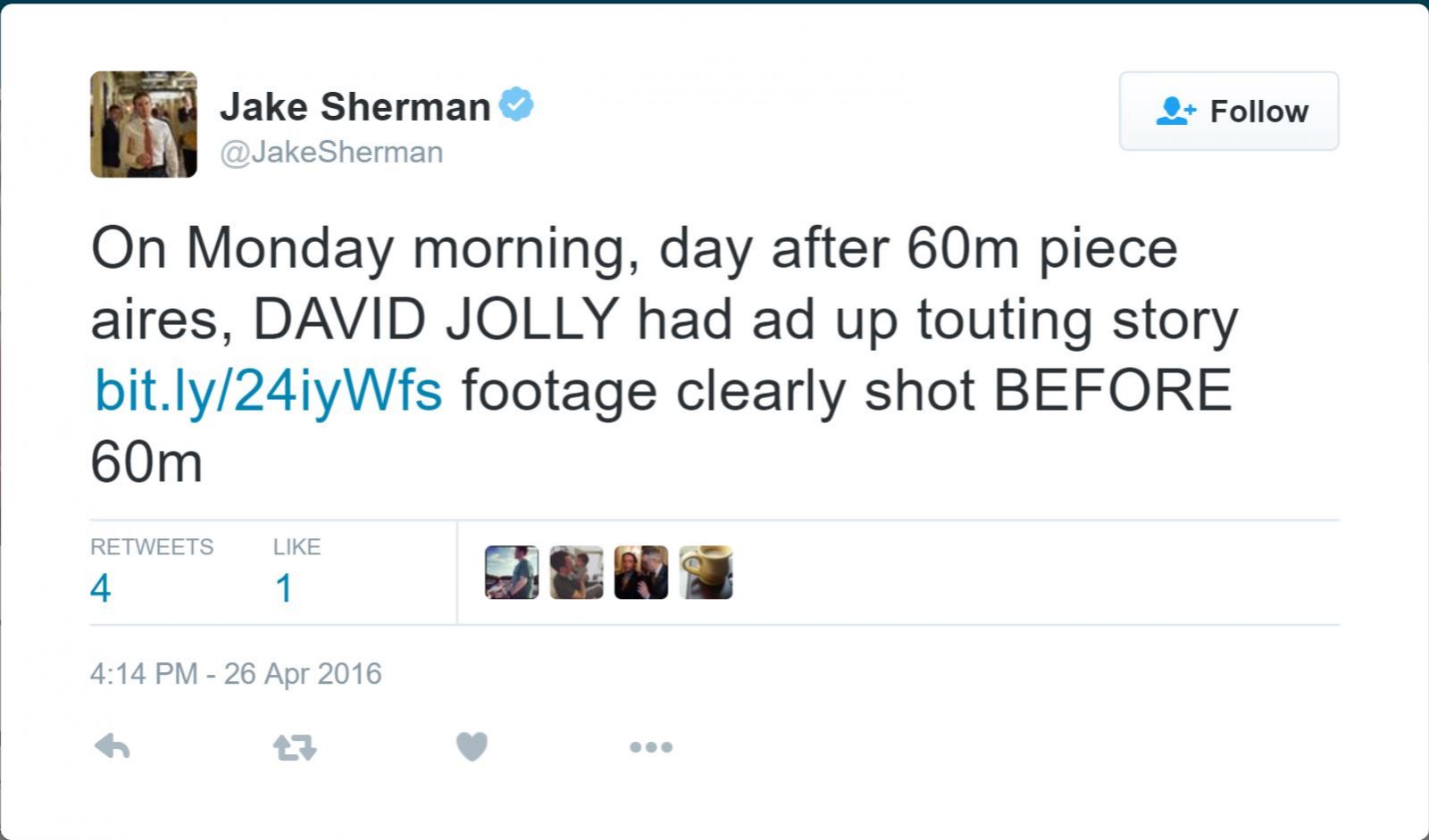

The move by Jolly, one of 10 Republicans who so far has expressed an interest in running for Rubio’s Senate seat (the ballot for the August 30 primary won’t be set until late June), immediately came under suspicion as a campaign stunt.

Jolly acknowledged in an interview with BillMoyers.com that his bill is a modest step. His so-called STOP Act would not ban members of Congress from accepting super PAC money or appearing at fundraisers. But they would not be allowed to personally solicit funds. That, Jolly argues, would eliminate one of the biggest time sucks in a lawmaker’s day.

“I’m not spending time in call suites,” said Jolly, who in his Senate race is abiding by his own proposed rules against personally soliciting donors. “Call suites” are rooms that both the Republican and Democratic parties set aside in offices, conveniently close to the US Capitol, where lawmakers can make the kind of campaign cash requests they are not legally permitted to make from their taxpayer-funded offices. In a New York Times op-ed earlier this year, retiring Rep. Steve Israel, an eight-term New York Democrat, confessed to having spent some 4,200 hours making telephone calls for political donations. Israel also is calling for an end to the congressional money-go-’round.

Making an issue of money in politics is smart strategy on Jolly’s part, says Susan MacManus, a political scientist at the University of South Florida. “It’s an issue that people feel passionately about,” said MacManus, who noted that the Tampa Bay area where Jolly’s district lies also is home to the mailman who last year was arrested for flying a gyrocopter onto the US Capitol grounds to the influence of campaign contributions.

Corroborating MacManus’ theory: Jolly picked up two new co-sponsors for his bill this week, both of them Democrats: Rep. Alan Grayson, who is seeking his party’s nomination in the Florida Senate race and so could potentially oppose Jolly this fall, and Rep. Brendan Boyle, a freshman who represents a district just outside Philadelphia. They join six other co-sponsors who signed on earlier this year: Republicans John Mica and Richard Nugent of Florida, Sean Duffy and Reid Ribble of Wisconsin, and Walter Jones of North Carolina — and one other Democrat, Richard Nolan of Minnesota.

A wider coalition remains elusive, however. Jolly and Rep. John Sarbanes, the Maryland Democrat who has his own legislation to reduce the influence of big money on congressional races, have talked, but so far have not been able to coalesce around an approach. Jolly says he’ll keep trying. “As a Republican, I’m willing to work with Sarbanes or whomever,” he said. “We all think there is too much money in politics.”

Until you raise $18,000 a day,

don’t even think about your

congressional business.

Jolly said he became convinced early. After he first won his US House seat in a March 2014 special election, Jolly said he had a meeting with a senior Republican who “wanted to help me out.” His colleague “sat me down” in front of a whiteboard, Jolly recalled, did some calculations and told the new congressman that to win a full term the following November, he’d have to raise $18,000 a day.

“Until you raise $18,000 a day, don’t even think about your congressional business,” Jolly recalled his mentor saying.

It’s no wonder the public feels lawmakers aren’t working in the nation’s interest, Jolly said. “They’re not even here! They’re across the street, shaking everybody down.”

Kathy Kiely, a Washington, DC-based journalist and teacher, has reported and edited national politics for a number of news organizations, including USA TODAY, National Journal, The New York Daily News and The Houston Post. She been involved in the coverage of every presidential campaign since 1980.