In Syria, Keeping the Faith

The suffering of Syrians comes to those of us outside the country in words and images. Violent scenes and anguished accounts pervade the international media. Reporters tell us who is fighting, and commentators ask why. How should the United States and others respond? What should be done about ISIS? About refugees? There are days when it seems we have reached a saturation point. No more talking, please—no more words.

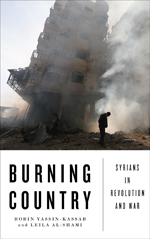

But that impulse, however understandable, is mistaken. In their new book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, journalist Robin Yassin-Kassab and human rights activist Leila Al-Shami provide a bracing and timely reminder that no matter how long the war rages or how unreachable a political settlement may appear, the world owes it to the Syrian people—especially the peaceful revolutionaries—to listen to their stories and support their cause. Burning Country is a portrait of the opposition, a movement of protest against Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime, which has been nearly forgotten amid the humanitarian strife, factionalism, and power politics surrounding and driving the conflict.

The regime’s extraordinary cruelty is well known, thanks to reporting such as Janine de Giovanni’s The Morning They Came For Us: Dispatches from Syria (2016), the latest in a long line of works detailing Assad’s bloody response to the revolution for democratic reform, economic opportunity, and an end to corruption and institutionalized violence. This revolution has its own lesser-known backstory, though, which Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami helpfully emphasize. Contrary to popular perception, 2011 was not the beginning. Calls for change emerged with the political openings accompanying the Damascus Spring movement in the early 2000s and the 2005 Damascus Declaration for Democratic National Change. Prominent civil and political figures of all backgrounds—secular and religious, Arab and Kurdish; the opposition, Muslim Brotherhood, Communist Labor Party—signed on. When I visited Damascus in 2009, the potential for democratic reform was palpable, if unspoken. Within limits, one could discuss and even debate issues such as women’s rights and Syria’s role in the region. My sense was that many Syrians, though mindful of the dangers, wanted change.

The Syrian uprising was not a reaction to the Arab Spring. It percolated for at least a decade before the protests of March 2011.

To appreciate the tenacity of the Syrian revolutionaries in the face of the regime’s violence, it is important for those outside the country to understand this history: the Syrian uprising was not a spur-of-the-moment reaction to the Arab Spring. It percolated just beneath the surface—and just beyond the headlines—for at least a decade before March 2011, when anti-regime graffiti drawn by schoolboys in the southern city of Daraa provoked Assad’s violent crackdown. It is also critical to recognize the depth of many Syrians’ disillusionment with a regime that has imprisoned, abused, and violated them. One evening during my 2009 visit, I had dinner with two weary but warm Syrian Kurds who had spent the prime of their lives in prison. I asked what outsiders could do to help people in their situation. “Tell our stories,” they replied. This is exactly what Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami do.

Perhaps in order to stress the peaceful aims and origins of what has devolved into a globalized civil war with sectarian overtones, Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami are careful to present a side of Syria that few now see: ordinary people surviving and helping others do the same. For instance, we meet Bashaar Abu Hadi, who works in children’s TV and explains, “In Aleppo, the people are determined to live and talk, despite Assad, despite America and the whole world. People get married and have children. I’ve seen a popcorn seller after a barrel bomb hit. He picked himself up, brushed the dust off his clothes, threw away the top layer of popcorn, and resumed his call to the customers.” Volunteers with the Karama (“dignity”) Bus circulate in heavily bombed areas of Idlib province, where they show children cartoons and read them stories to help cope with the aftermath of bombardment. Two-and-a-half-thousand copies of the magazine Zawraq (“boat”), founded by two teachers, are distributed to children deprived of school in the liberated north and in Turkish refugee camps.

Also lost from the standard storyline is the continuing effort of regime opponents to reclaim sovereignty using peaceful methods of persuasion. Some have adopted the revolutionary anticolonial flag (an anti-French symbol first flown in 1932) to replace Assad’s Baathist one. The flag’s three stars represent three uprisings: by the Alawi Saleh al-Ali, the Druze Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, and the Aleppo-born Ottoman official Ibrahim Hanano. The revival of the standard “not only expressed rejection of the Baathist interlude,” the authors write, “but also drew obvious parallels between colonial and neocolonial rule.” Then there is the popular online project Stamps of the Syrian Revolution, commemorating heroes and events of the current struggle. And educators are doing what they can to inculcate the values of a new society. The Return School, run by refugee volunteers in the “cramped, wind-blown tents” of a displaced persons’ camp in the northern village of Atmeh, follows the Syrian curriculum, but pictures of the president are torn from the textbooks. Across the border in Turkey, the Syrian-Canadian headmistress of the Salaam School prioritizes teacher involvement in collective decision-making, a sort of modeling of unfamiliar democratic norms.

Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami take us back to the nonviolent local coordination committees,tanseeqiyat, founded in the early days of the revolution to manage local affairs in the vacuum left by the regime’s departure from rebel-held territories. The authors report that as of July 2013 there were 198 such committees throughout the country, with some sources reporting more than twice that figure. One organizer describes the committees as “trust networks . . . just five or seven full-time revolutionaries in each neighborhood, working in total secrecy, but linked up to other networks throughout the city.” The committees are the heart of the revolution, offering solidarity and services to local residents and communicating to the outside world the desperate circumstances of ordinary Syrians living under Assad’s onslaught. But the tanseeqiyat are struggling to stay alive, thanks in part to Russian attacks even on towns where ISIS has little presence.

As Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami see it, it is the democratic aspirations of the Syrian people, represented by the committees and other activists, and not some supposedly irreducible sectarianism, that has led to the Islamicization of the conflict. Monzer al-Sallal, an activist and local official in Aleppo-adjacent Manbij, explains, “We used to laugh at the regime propaganda about Salafist gangs and Islamic emirates. Then the regime created the conditions to make it happen.” Faced with growing democratic opposition, Assad reasoned that domestic and international fence sitters would back him if the alternative to regime control appeared to be Islamic extremism. He abetted the rise of ISIS and other Islamists by releasing political prisoners known to have Islamist sympathies from Sadnaya military prison. He created a safe path for ISIS to attack the Free Syrian Army and seize their weapons, and he avoided bombing ISIS in order to focus on eliminating non-Islamist rebels. Assad’s strategy of forcing the world to choose between his regime and ISIS has largely paid off.

Before he cultivated Islamists to stifle democratic action, Assad did the work himself via a divide-and-rule strategy he learned from the previous ruler—his father, Hafez. As Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami write, communal tensions in Syria “are the result not of ancient enmities but of contemporary political machinations.” Both Assads used violence, fear mongering, and desperation to stoke internal discord, the better to convince imperiled minorities and the rest of the world that Syria is too disjointed and unstable for democracy. In the case of the Alawi community, the leadership has simultaneously provided opportunities for economic and political while cultivating fear of exclusion. Many Alawis now depend on military and government jobs and worry that their perceived affiliation with the regime will lead to displacement, unemployment, and collective punishment if it falls. The regime makes the most of these fears in an effort to ensure that Alawis and other vulnerable communities remain loyal rather than casting their lot with the revolutionaries.

Despite these efforts, many Alawis joined the revolution from the beginning. Others, the authors explain, such as the activist and rapper Abo Hajar, resisted the categories imposed by the regime. Hailing from the regime-controlled coastal city of Tartous and describing himself as “neither Sunni nor Alawi,” Abo Hajar helped to found Ahrar Tartous (Free Tartous), which welcomed all comers and coordinated with other cross-sect committees in the neighboring towns of Banyas and Safita.

• • •

“In many ways Assad has already fallen,” Yassin-Kassab recently told a Chicago public radio station, a point echoed at the end of the book. There is no doubt that for many revolutionary Syrians, at home and abroad, Assad is president in name only and will never regain the authority he once held. But while this makes for appealing rhetoric, the realities of the conflict suggest Yassin-Kassab’s confidence is misplaced. Assad appears to be settling in for the long haul. The war is now globalized and entrenched, with the United States, Russia, Iran, European nations, Turkey, and several Gulf states involved. The nuance with which Yassin-Kassab and al-Shami treat the opposition seems somewhat lacking in their treatment of the complex and tragic politics surrounding the internationalization of the conflict, which has helped Assad maintain his position.

The role of the United States is a case in point. Like most of the revolutionaries with whom they sympathize, the authors oppose U.S. military intervention. They also decry President Obama’s handling of the war, accusing him of handing “the Syria file” to the Russians. But while such criticisms may be justified, it is unclear what the authors expect instead from the United States, other countries, and the array of nongovernmental groups and international authorities shaping the conflict. One can infer that, in the early days, they wanted from the United States more than moral support for the peaceful revolutionaries. But that opportunity is long passed. Late in the book they call for the United States to provide weapons rather than training. If further intervention is unavoidable, they hope the U.S. military will fight the regime, not just ISIS.

The problem is that U.S. support can be the kiss of death. In the Middle East and elsewhere, opposition groups outfitted or sanctioned by the United States are frequently tarred as neocolonial puppets, marginalized and stamped out. Greater support for the “real” revolutionaries through unofficial, nongovernmental channels might have been an option, but the authors repeatedly stress the significance of grassroots uprising—a Syrian movement for democracy traversing class, sect, gender, and other markers of difference. Most revolutionaries did not, and still do not, see American help as part of the formula. U.S. involvement is simply too risky, bringing violence, sectarianism, and dependence on an outside power. Political debts owed to the United States would have to be paid in a post-Assad era, diverting scarce resources from the immense challenge of building a democratic Syria.

Among the war’s many tragedies is the lack of an obvious role for concerned outsiders seeking to aid the democratic revolution. There are many ways for foreign powers to hinder that enterprise—look no farther than Russia’s engagement on Assad’s behalf. But what could the United States have done to spur political change? The U.S. track record in the region suggests that almost any form of military intervention is likely to exacerbate the revolutionaries’ predicament, impaled as they are on the horns of ISIS and the regime. The U.S. invasion of Iraq and the sectarianization of Iraqi politics encouraged by American officials enabled Assad to play the sectarian card with relative impunity, extending his oppressive rule and drawing outside powers more deeply into Syria. Today the bankruptcy of sectarian politics is evident across the region—from ongoing democratic protests against Lebanon’s officially sectarian government, to Israel’s dangerously sectarian military recruitment practices and divisive divide-and-rule strategy, to Iraq, where citizens backed by the cleric Muqtada al-Sadr are demanding a technocratic replacement for the failed, U.S.-brokered government.

But while U.S. engagement can be perilous, the United States could, and should, do more to help Syrians develop a political solution that ends the violence. That means ceasing U.S. bombing, which brings death and destruction to the people of Syria and fuels ISIS recruitment. It requires that the United States increase pressure on Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to grant Sunnis a fair place in Iraqi political life, undercutting the incentive to join ISIS. More immediately, policymakers can assist Syrians who have been forced to flee, and these officials should start focusing more on causes—Assad’s oppression—than symptoms, exemplified by the growth of ISIS. Because, as Burning Country so powerfully shows, it is Bashar al-Assad more than anyone else who has created this nightmare. There may be a future for Syrians who manage to escape, but there will be no future for Syria until he is gone.

[Elizabeth Shakman Hurd teaches and writes on the politics of religion, U.S. foreign relations, and the global politics of the Middle East at Northwestern University, where she is associate professor of politics. Her most recent book is Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion (Princeton, 2015).]