By Mark Solomon

June 26, 2016

Portside

There is a now well-known aphorism from the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks: "The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Those "morbid symptoms" abound. Heading an increasingly familiar list is neoliberal globalization whose vast reach and now time-worn promises of global community are confounded by near universal upheaval: whole populations uprooted by economic contraction, environmental destruction, political and religious conflict punctuated by endless wars, desperate immigrants, persisting hunger and disease.

"Mature" industrialized countries remain in the grip of a nearly half-century of stagnation and decline manifested in near-abandonment of domestic commodity production and decent jobs. Capital persists in a race to the bottom in search of the most exploitative and profitable arenas where wages are lowest, unions are weak or non-nonexistent, workers are coerced by the state, taxes are scandalously minimal and where life-threatening environmental degradation is left in its wake.

Dominating the ideological landscape is neoliberalism - the doctrine of individual survival rooted in dependence upon unfettered markets - rejecting government-driven social programs established by the collective will of working people. Workers are handed austerity while the super-rich wallow in speculative fortunes - "financialization" based on impenetrable financial instruments often involving outright criminality.

Neoliberal globalization is the driver of galloping inequality; the 99% vs. the 1% articulated in 2011 by Occupy Wall Street. That polarization of wealth and poverty weighs heaviest on communities of color and other vulnerable populations reflected in mass incarceration, intensified assaults on immigrants, and increasingly undisguised bigotry aimed at Latinos, African Americans, women, the LGBTQ community - nurturing a climate of division as a counter to aspiring broadly-based unity to combat social injustice.

In the midst of those "morbid symptoms," the concept of a "precariat" has emerged. That term initially applied to a vast segment of the work force that lived on "precarious" employment - part time work at low wages, contingent and contract labor, jobs bereft of minimal security against firing. Currently, the term's meaning can be expanded to include full-time workers whose "middle class" incomes fail to provide adequate protection against bankruptcy, catastrophic illness, sudden joblessness and escalating cost of living in gentrifying urban communities.

A decade ago, there was evidence that the emerging millennial generation would face unparalleled economic constriction and sharply rising educational costs. It was destined to become the first post World War II generation with less financial wealth and fewer prospects than its parents. That tightening bind would foster in that generation an unprecedented militancy and for many among them an openness to an alternative social system unencumbered by the fading memory of the Cold War. That militancy grounded in economic challenge would inevitably equal and transcend the political commitment of the heroic generation that rose in the sixties to oppose the Vietnam War and support Black Liberation.

As rays of hope began to break through those "morbid symptoms," strong opposition emerged to systemic police violence, principally aimed at African American youth. Black Lives Matter became a pivotal force in awakening protest and resistance to the long train of police violence against black men and women - leading a growing multiracial movement to challenge a criminal justice system steeped in racism. The force of that growing protest began to bring down symbols of oppression in South Carolina and elsewhere.

Abysmally low wages enshrined in an emergent service economy was challenged by a fifteen-dollar-an-hour movement largely engaging a rising generation of young people of color. At the same time, new forms of labor organization like community-based workers' centers supplemented resurgent union combativeness symbolized by the successful Verizon strike.

A growing and increasingly militant environmental movement - commensurate with the urgency of the ecological crisis challenged and at times defeated the fossil fuel industry. Movements to defend women's reproductive choice, LGBTQ rights, movements to overturn Citizens United and combat voter suppression, movements to fight student debt, movements for universal health care and economic justice all impacted Bernie Sanders' remarkable presidential campaign.

At its political core, the Sanders campaign's unexpected success was movement driven. The "revolution" affirmed the importance of electoral battle joined to mass movements. It established a left pole in the country's political life that cannot be ignored. After a century of disregard, it brought socialism back into public discourse. Its thirteen million votes, its twenty-two primary and caucus victories, its huge rallies, its large grass roots ground operation and its ability to raise tens of millions in small contributions - all confounded and undermined the two-party duopoly, opening the door to unanticipated prospects for the left in electoral struggle. In that regard, the campaign confirmed that the Democratic Party can become contested terrain. And - it struck a deeply responsive chord among young people, unlocking powerful energy in the millennial generation that has, as Sanders proclaimed, "won the future."

The critical questions that follow are not meant to denigrate the achievements of the Sanders campaign, but to raise issues that would hopefully contribute to advancing and consolidating the movement.

Among the most consequential issues that faced the campaign was race and the votes of African Americans. The massive totals run up by Hillary Clinton among black voters in the South in the primaries' early stages, and the Clinton chokehold over super delegates, made it nearly impossible for Sanders to make up that lost ground and negated any realistic hope of winning the nomination. Sanders' overwhelming defeat in the final Washington, DC primary signified that the weakness with black voters persisted to the end.

Many pundits, often with a patronizing touch, have sought to "explain" overwhelming African American support for Clinton. At the outset, it must be noted that the African American vote was never monolithic. Sanders earned the fervent support of significant cluster of black political and cultural figures; black youth, in tandem with young white voters, strongly supported Sanders; even when overwhelmingly defeated, Sanders won twenty to twenty-five percent of African American votes.

Many reasons have been offered for the sweeping African American support for Clinton: concern about the threat from the racist right and fear that a generally unknown and untested Sanders would be a risky choice; long-time familiarity with the Clintons' that included a degree of cultural affinity and comfort; Hillary Clinton's tight embrace of Barack Obama and his legacy.

Not generally acknowledged is the historic impact of the civil rights upsurge of the sixties that brought a qualitative realignment of southern politics. Large-scale white abandonment of the Democratic Party and the ascension of the Republicans as the dominant political force undergirded by white supremacy resonated deeply with black voters who became the reliable base for the Democrats. The dominant right wing soon equated allegiance to the Democratic Party as virtually akin to an embrace of communism.

As racist assaults on the Democratic Party persisted, African American voters clung tenaciously to the Party and to its history of support for civil rights. In that context, Hillary Clinton, justly or not, came to personify that history while the less known Bernie Sanders was not able to similarly connect with it. That was crucial in the South and clearly had an impact among northern African American voters.

Given the limits imposed by time and a small organization in the South, it can be argued that there was little that Sanders could do to turn the tide. A significant effort in South Carolina yielded much the same defeat as elsewhere in the region. Yet, it did not help for Sanders to characterize the entire region as "conservative." That undercut an appreciation of the progressive current represented by southern black voters and the potential for opening a sympathetic dialogue with those voters as well as advancing black-white unity exemplified by the Moral Monday movement in North Carolina. The need to build an ongoing national progressive force (the "revolution" that Sanders calls for) must find ways to connect with the progressive aspirations of black voters, South and North, and with all emergent forces seeking multiracial cooperation.

Had the Sanders campaign demonstrated greater sensitivity to the early challenge posed by black voters, it might have considered a major address similar to Barack Obama's broad exploration in 2008 of the country's racial history in response to attacks on his relationship with the outspoken Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Sanders could have addressed the working people of all races, condemning institutional racism at the heart of the country's economic and social life. He could have located racial injustice in the marrow of the "billionaire class" and could have denounced white supremacy as a fraudulent pabulum tendered to white labor in order to garner super profits while dragging down the living standards of all races. An address of that nature could have affirmed Bernie Sanders as a thoughtful, probing partisan for racial justice.

While Sanders' calls for an end to a corrupt criminal justice system and institutional racism grew stronger during the campaign, his platform points regarding racial justice came across as undifferentiated items in a "laundry list" of demands. The campaign's overarching anti-Wall Street theme tended towards abstraction without clear reference to concrete problems. For example, his assaults on the criminal activities of big banks never connected the sub-prime bubble collapse to the special targeted victimization of African American and other national minority home buyers.

An indisputable lesson of the Sanders-led upsurge is the centrality of the roles of African American, Latino women and men and other oppressed nationalities in building a permanent, powerful and transformative movement for change. A number of grass roots initiatives have emerged such as Brand New Congress, the People's Summit, the United Progressive Party and others seeking to sustain and build upon the energy and political health of the Sanders campaign. That variety of approaches and forms is to be expected at this early post-primary stage. However, none is likely to succeed without tackling the centrality of race and white supremacy. Nor will there be much success unless those forces reach out to oppressed nationalities, inviting them at the start to build a genuinely collaborative multiracial endeavor.

Similarly, Sanders' strong program relating to women did not clearly tie gender discrimination to Wall Street's sway over the economy and polity. That deprived the campaign of a penetrating analysis of the systemic nature, beyond the recitation of issues, of discrimination against women. An ongoing movement needs to explore those deeper questions in order to secure broadly-based trust and unity.

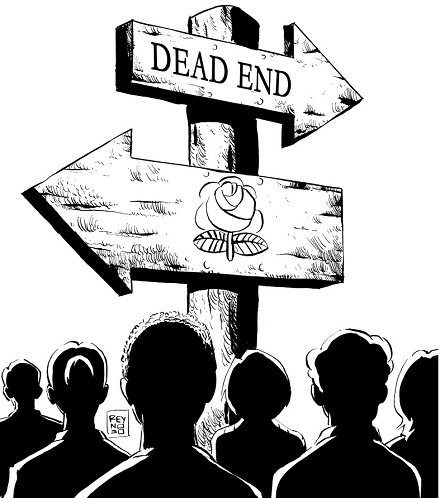

Whether the post-campaign evolves into a national left pole organization or coalition contesting within the Democratic Party, whether it evolves into a new national party or whether it continues as a decentralized series of initiatives - there appears to be no emerging strategy beyond Sanders' pleas for activists to run for office at all levels.

Without a strategy, a movement becomes rudderless, listing without direction and susceptible to injurious forces that do possess a strategy. A strategic starting point for the Sanders movement could be an effort to forge a progressive majority powerful enough to break the right wing Republican stranglehold over Congress and begin to realize the redistributive dynamics inherent in Sanders' program.

As strong and energetic as the Sanders revolution proved to be, it has yet to achieve the breadth of numbers required to impose the democratic will to defeat the right, to make fifteen dollars federal law, brake ecological disaster, curb Wall Street, enact universal health care, pass tuition-free public higher education, produce campaign finance reform, transform a bankrupt criminal justice system, advance a non-interventionist foreign policy, etc. Qualitative advances on those vital issues require the broadening of the movement to embrace center forces - many of which can be won to advocacy of those demands rooted in the Economic Bill of Rights advanced by Franklin D. Roosevelt in the waning days of World War II.

A significant factor in building a left-center progressive majority is the large bloc that voted for Hillary Clinton in the primaries. That bloc, distinct from Clinton, has not received the attention and analysis commensurate with its importance. Bernie Sanders registered impressive votes in conservative states like Idaho and Kansas, but why did he somewhat consistently come up short in largely multiracial areas that normally support progressive policies and candidates? Surely, many Clinton voters were motivated by the historic prospect of the first major female presidential candidacy; others may have been accustomed to marching in lockstep with Democratic organizations and elected officials; many also might have been moved by Clinton's human rights rhetoric and many may have bought into the Clinton message of competence and "realistic" incrementalism.

The Clinton vote was not inherently regressive. Exit polling and interviews revealed that many voted for Clinton with trepidation, with conflicted sympathy for Sanders, or with a melancholy conviction, cultivated by media and the dominant political culture, that Sanders could not win.

A distinction must be drawn between neoliberal corporate centrism represented by Hillary Clinton with her Wall Street supporters and the centrism of many Clinton voters who generally support Sanders' program but have fallen prey to the pragmatic posture of skepticism about transformative change that has been in the country's marrow for centuries.

However, the horrific economic and social conditions described early in this essay can embolden legions of working people to join forces with the Sanders left to ultimately jettison tepid centrism. The North Carolina Moral Monday movement - an inclusive multi-issue challenge to the right led with consummate skill by the Reverend William Barber II, head of the state NAACP, is an excellent example of what can be achieved.

A crucial strategic objective is to build a left-center majority to defeat the right and advance a progressive agenda. Key to that is the cluster of large, powerful unions and national organizations that supported Hillary Clinton. No matter how tawdry their motives in endorsing Clinton (like some grasping for access to the presumptive nominee - a striking contrast to the courageous unions that endorsed Sanders), they cannot be downgraded or ignored in pursuit of a winning strategy.

Those major unions that joined the Clinton bandwagon, some with left roots, can be by approached by the Sanders movement to join in demanding that the next Administration urgently responds to the country's critical needs. The elements of the Sanders program that correspond most to labor's own interests can be prioritized. The AFL-CIO, the American Federation of Teachers, NEA, UAW, SEIU, AFSCME and some others possess the resources, organization and cohesion to play a role is helping the vast Sanders youth component to adopt a strong, permanent presence. Similarly, large national organizations, like Planned Parenthood, the NAACP, liberal and progressive churches and single-issue groups can be called upon to ally with the newly insurgent movements - Sanders youth, Black Lives Matter, 15-dollars-an-hour, etc., to extend support to the rising millennial generation.

Bernie Sanders has called upon activists to contest for office from local school committees and municipal councils to Congress. That exciting objective cannot be brought to fruition without a lot of organizational effort. Programs would have to be established to survey and analyze specific constituencies and prospects; candidates would have be solicited and trained; issues would have to be developed and tested; ground workers would have to be nurtured and considerable money raised; social networks would have to be developed and widely utilized.

Well-rooted national unions and organizations have the resources and structures to help cultivate and fund those candidacies. The forging of left-center coalitions in the electoral arena is an admittedly challenging, but essential aspect of advancing the remarkable forces and energy unleashed by the Sanders campaign. It also can extend support to the Sanders youth movement by helping to provide it with organizational experience, coherence and permanence.

A left-center convergence with its potentially transformative numbers is mandatory for the immediate strategic goal of decisively defeating Donald Trump and the right wing challenge. The danger represented by Trump cannot be minimized. The Brexit vote is yet another example, among many, of the lethal mix of racism and demagogic right wing populism that combines searing anger at the inequality and austerity of neoliberalism with relentless racism and bigotry. Trump's bogus "outsider" persona still combines with his crude and vulgar facade to magically become an effective "tell it like it is" contrast to a mendacious establishment.

A few progressives have become beguiled by Trump's vague feints towards diminishing NATO and towards "deal making" with adversaries. More concrete however is his stated goal of increasing the military beyond its already ridiculously bloated size and his cavalier interest in proliferating nuclear weapons. Trump's hugely ignorant views on the environmental crisis alone, turns his possible election into a literal existential crisis. On top of that, Trump's election (still possible) would make racism state policy.

The strategic objective of a left-center alliance to defeat the right, holds within it the potential to extend the influence of the left as the collaboration deepens and grows. Thus, Bernie Sanders was solidly on target to point that defeat of Trump is not the endgame; that the movement needs to develop beyond its defeat of the right to affect a deeper social transformation. As the alliance continues to grapple with the crisis of neoliberal globalization, the left can influence the center by virtue of its ideas and commitment to qualitatively overcome the present crisis and usher in a revolution of expanded democracy and redistribution of wealth.

The strategy of a left-center alliance would be strengthened and consolidated by a mature, mass-oriented convergence of seasoned socialist forces. Such a formation is critical to the process of qualitatively advancing and coalescing left and center political forces by constructively pointing out shortcomings and ongoing challenges. There is the critical importance of linking issues and building multi-issue cooperation, the need to confront and overcome an interventionist foreign and military policy; there is the importance of establishing a seamless relationship between electoral and non-electoral policies and a non-contradictory relationship between elements of the alliance that contest in the Democratic Party and those working to build an independent party or formation; there is the need to build multiracial unity and in that effort, to talk respectfully with white workers about the costs to them of institutional racism.

Left and progressive forces have taken giant, nearly unprecedented steps in the recent primaries. The emergence of a new, activist and progressive generation bodes well for the present and holds great promise for the future. Regardless of what happens in coming days - whether Clinton, Sanders or Trump or some unforeseen player ascends to the White House, the need for a broad, majoritarian progressive movement will be mandatory.

At the same time, the country is entering a period of historic realignment of its political structures. Both parties are confronting internal breakup, the consequences of which are as yet unforeseen. A striking analogy from history is the decade before the Civil War that was characterized by internal tensions over slavery in the major Democratic and Whig parties that led to their internal fracturing and the emergence of a mass anti-slavery party, the Republican Party. In that process, a major segment of the abolitionist movement understood that the successful emergence of a new anti-slavery party required the cultivation of anti-slavery forces in both major parties, the creation of an independent new party as a vessel for those leaving the old parties, and a breadth of vision that embraced the aspiration of liberation. Let's hope that the newly energized progressive forces today grasp the vision and spiritual generosity of the 19th century abolitionists. With so much at stake the emergent progressive majority must prevail to secure peace, democracy and justice.

[Mark Solomon is an Associate at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University; He is past national co-chair of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS) and is author of The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans (University Press of Mississippi).]

By Joseph M. Schwartz

June 27, 2016

credit: Frank Reynoso

Bernie Sanders’s campaign for president may have started a political revolution, but the question to consider well before Election Day is how to continue that revolution. The campaign arose out of popular rebellion against the bipartisan politics of austerity manifested in the Battle of Wisconsin, Occupy Wall Street, the low-wage justice movement, #BlackLivesMatter, and the immigrant rights movement.

At this writing in mid-May, it’s a fair bet that the campaign will focus its energy on platform fights at the Democratic convention in favor of a $15 national minimum wage, single-payer health care, fair trade rather than free trade, public campaign finance, and a democratic and grassroots-funded Democratic Party. No matter who wins the nomination, these planks provide a benchmark against which to measure a candidate.

Start Now to Broaden the Sanders Movement

Political campaigns, particularly presidential ones, rarely yield ongoing grassroots political organization. That will be the responsibility of the activists and organizations that built the Sanders campaign at the local level. These local efforts will be greatly enhanced if the Sanders campaign shares its list of activists and donors with local organizers and if several of the key institutional players in the campaign (such as the Communication Workers of America, the National Nurses Union, and the Working Families Party) provide funding. But even if such resources are lacking, local Bernie activists, particularly those associated with the independent volunteer networks of People for Bernie and Labor for Bernie, should work to build local coalitions that can continue the “political revolution.”

That is, the “Bernie current” in U.S. politics needs to be built primarily from the grassroots up and should focus primarily on state and local politics. Republican control of all three branches of government in 25 states has had disastrous consequences for education funding, voting rights, labor rights, and reproductive justice. Fifty separate political systems exist in the United States; only if we build rainbow coalitions at the state and local level, such as the Moral Monday movement in North Carolina, can the left match the political power that the right has built in the past 40 years. The left needs to build the base for a multi-racial group of Bernies and Bernices running not just for Congress, but for school boards, city councils, and state legislatures.

Coalition Politics

These local coalitions must be more multi-racial in nature than the Sanders campaign itself. As labor and community activist Bill Fletcher argued in the Spring 2016 issue ofDemocratic Left, the Sanders campaign did not go boldly into black and Latino community spaces, such as the church, and focus concerted attention on issues uniquely salient to those communities: an end to mass incarceration and police brutality and immigrants’ rights. Sanders addressed these issues, but almost always in the context of his standard stump speech railing against the oligarchy’s role in promoting socio-economic inequality. The Democratic Party elite remains pro-corporate and neo-liberal in its policy orientation, but communities of color understand that there are real differences between the two parties on voting rights, reproductive justice, labor rights, and immigrants’ rights. They’ve seen what Republican control of all three branches of state government has meant for working people and people of color in formerly Democratic states such as Wisconsin and Michigan.

Community activists in and around the Sanders campaign should start now to form local, post-election organizations or coalitions to first “Dump Trump” while simultaneously beginning to build political capacity independent of the Democratic Party establishment. Independent activist networks, as well as progressive unions and organizations such as Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) that backed Sanders from the start will also be key to such efforts. But such local efforts must move beyond the primary base of the Sanders movement among older white progressives and younger (somewhat more multi-racial) millennials. That is, the post-election trend must construct a multi-racial, majoritarian left and can only do so by tackling the intersectional nature of race, class, and gender injustice. To that end, Sanders activists should prioritize work as loyal allies in anti-racist struggles led by activists and organizations rooted in working-class and poor communities of color.

Labor and Community Organizations

Organized labor must also be central to such efforts, particularly as labor unions are often the only multi-racial institutions in a community. Unfortunately, not all union locals, even if affiliated with progressive internationals, are committed to democratic rank-and-file political mobilization. Those that are can play an invaluable role in progressive coalition politics.

To accomplish the above, post-election activists will have to accurately map the diverse nature of their potential allies and analyze the local power structure (including those Democratic Party elites opposed to radical change). This analysis must survey both mainstream and radical people-of-color organizations, taking into account the full range of diversity in generation, ideology, and class composition in such communities, as well as both the history of cooperation and tension between ethnic and racial groups in the community. Only by doing so can activists comprehend which groups have a mass base and will be the best partners for social change. The African-American-led progressive coalitions that recently defeated conservative incumbents for district attorney in Cleveland and Chicago are prime examples of such multi-racial efforts.

Post-election Activism

Although DSA is growing rapidly because of Sanders’s legitimation of democratic socialism and the attraction of millennials to socialism, we still have limited resources and must use them strategically. Our post–November priority is to build the capacity of our locals to engage in anti-racist coalition work, for all of the reasons mentioned above.

This summer and fall DSAers will be focusing on two local campaigns that pre-figure the type of political efforts that can build a post-election left political current. DSA will work to elect DSAer Debbie Medina to the 18th district of the New York State Senate (the Bushwick and Williamsburg sections of Brooklyn) in the September New York Democratic primary (seeinterview. Medina, a veteran Puerto Rican activist and an explicit democratic socialist, is focusing her campaign on affordable housing, equitable public education, and the fight for racial justice. In North Carolina, our fledgling Piedmont local is aiding political independent Eric Fink’s run for the State Senate. Fink, a long-time DSA member and labor law professor at Elon University, is the sole opponent in District 26 to infamous Republican State Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger, a key proponent of the trans-phobic HB2 “bathroom bill.” Fink’s campaign aims to strengthen the multi-racial Moral Monday movement. (Also of note is left-leaning Tim Canova’s campaign against Democratic National Committee chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz in Florida.)

This is the beginning of DSA’s work to build a socialist trend in the streets and in electoral politics. Despite what mainstream pundits say, we can afford all that “free stuff” (also known as social rights), if we redistribute the income and wealth that the 1% have extracted from the 99%. In addition, socialists can best articulate that public investment can often be more productive than private capital. Only major public investments in nonprofit housing, alternative energy, mass transit, and infrastructure can create a sustainable, just society. Targeting these investments to address the racial wealth divide will necessitate building a socialist movement that is as diverse as the working class, a movement that values different cultures, is forthrightly anti-racist, and grounds its politics in mutual support and inter-racial solidarity.

This article originally appeared in the summer 2016 (early June) issue of the Democratic Left magazine.

Update:

The above was written in mid-May for mid-June publication in the print edition of Democratic Left.

The following is a postscript by the author, written after the final June primaries.

The left should build off the success of the Sanders campaign by building a multi-racial coalition that puts front-and-center the “intersectional” nature of class, gender, and racial oppression. While capitalism and class relations play a key role in structuring forms of racial and gender oppression, racism and patriarchy also have an independent logic. Women, LGBTQ people, and people of color face forms of violence and domination that cross-cut class (e.g., affluent people of color face discrimination in the housing and labor market and are often subject to police harassment).

Bernie did not pull off a miracle victory, but we should be empowered by how close he came to doing so. An avowed democratic socialist just introduced the country to the basics of a social democratic platform and received 43% of the Democratic primary vote, or 12 million votes! This is something to build off of rather than to lament. (Over 20% of those votes came from voters of color, particularly voters under 35. If Sanders had won 15% more of the black and Latino vote he would have won the majority of pledged delegates). In contrast, Ralph Nader only received 2.7 million votes in his 2000 general election, third party campaign. At best, 5% of Nader’s vote came from people of color.

Yes, the Democratic establishment, embodied by DNC chair Debbie Wasserman-Schultz, tilted the playing field against Bernie—what did one expect? But by building political capacity independent of monied interests and the Democratic Party establishment, Bernie used the primary process to further an independent left politics. As the states run the primaries, neither party establishment can ban anyone from running (do we think the ruling class really wanted Trump to be the Republican nominee?). Thus, anti-corporate, pro-labor progressives do sit in Congress (see Raul Grijalva, Keith Ellison,Jim McDermott, Marcy Kaptur, Barbara Lee, the list goes on), though such figures usually represent majority black or Latino districts or areas with a strong progressive trade union presence.

The Trump phenomenon has made Republican “dog-whistle” racist politics explicit. Such a racist, anti-immigrant, misogynist and anti-Muslim politics must be defeated and defeated soundly. While the majority of Trump’s base are college-educated small-town businesspeople and low-level managers (often from deindustrialized smaller cities), his protectionist policies and immigrant bashing does appeal to a significant segment of older downwardly-mobile white working class individuals (particularly men). But as Bernie’s campaign proves, a left candidate who aggressively defends the interests of working people by fighting to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, to establish free public college and universities and to institute “fair trade” rather than free trade policies, can win over a large segment of the white working class, while advocating an expedited path to citizenship for the undocumented.

While we can’t trust the former Senator from Wall Street to enact such policies, forcing Clinton to run on a more populist, pro-working class platform will help us build street heat against her administration if and when it fails to break with the interests of the 1%. Electing a Democratic Senate would also weaken the neoliberal Democratic excuse “that the Republicans prevent us from doing anything progressive.” A Trump victory would let neoliberal Democrats off the hook, as they will claim that their social liberalism stands up to Trump’s extremism. We must defeat Trump, given what his administration would likely do to immigrant rights, reproductive rights, voting rights, environmental policy, and labor rights. And we should have no illusions about the candidate who will have to defeat him.

[Joseph M. Schwartz is a professor of political science at Temple University and a National Vice-Chair of DSA. He is currently working on a book on the roots and revival of U.S. socialism.]

By David L. Wilson, Truthout Op-Ed

June 29, 2016

US Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont speaks with supporters at a rally in Phoenix, Arizona, on July 18, 2015.

Photo: Gage Skidmore // Truthout

It's been an astonishing year for the US left. Issues that mainstream politicians would have declared "off the table" just 12 months ago -- free public higher education, universal health care, the $15 minimum wage, a national ban on fracking -- are now acceptable topics for public discussion. A US politician who declared himself a socialist won more than

12 million votes, and even dared to advocate equitable treatment for

Palestinians.

Bernie Sanders' campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination has accomplished more than most of us could have imagined a year ago. But what happens now that Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are almost certain to be our "choices" in the fall?

Some of the millions energized by Sanders' primary bid will come out to work for Trump's defeat, others will campaign for progressive

congressional candidates and still others will use the election season to build for a

third party. The Sanders campaign itself seems focused on pushing reforms at the Democratic convention in July. These may all be worthwhile activities, but the fact is that election periods have an expiration date: Once an election has passed, only a small number of committed people remain excited by long-range electoral projects.

The establishment politicians and the billionaires are expecting -- and counting on -- demoralization and a falloff of political activism after November. But a return to "politics as usual" isn't inevitable. History suggests a very different possibility.

After the Political Struggle

More than 100 years ago, the Polish-German revolutionary and economist Rosa Luxemburg explained that real political change doesn't come through political action alone; it requires what she called "the interaction of the political and the economic struggle."

"Every great political mass action, after it has attained its political highest point," Luxemburg wrote in 1906,

breaks up into a mass of economic strikes.… With the spreading, clarifying and involution of the political struggle, the economic struggle not only does not recede, but extends, organizes and becomes involved in equal measure. Between the two there is the most complete reciprocal action.

Every new onset and every fresh victory of the political struggle is transformed into a powerful impetus for the economic struggle, extending at the same time its external possibilities and intensifying the inner urge of the workers to better their position and their desire to struggle. After every foaming wave of political action a fructifying deposit remains behind from which a thousand stalks of economic struggle shoot forth.

We may prefer less flowery language today, and "grassroots struggle" would be a more meaningful expression for us now than "economic struggle." Luxemburg was writing about the series of strikes around wage and workplace issues that culminated in the 1905 Russian Revolution; the equivalent struggles in the United States today arise from social and environmental issues, as well as economic demands. But her basic analysis remains as relevant as ever.

The emergence of the Sanders campaign itself follows the pattern Luxemburg identified.

Initial activist responses to the 2008 economic crisis took the form of local grassroots struggles -- the workers' takeover at Chicago's Republic Windows and Doors in December 2008, for example, and the occupation of Wisconsin's capitol building by unionists and their supporters in February 2011. The first large-scalepolitical response came with Occupy Wall Street in the fall of 2011. Occupy receded quickly, to the great relief of the billionaires and their media spokespeople, but it left behind Luxemburg's "fructifying deposit."

In the years since 2011, previously existing grassroots movements have gained a fresh vitality, and other new movements have sprung up. This general upswing in organizing is apparent in actions by the immigrant youths known as Dreamers; inBlack Lives Matter; in protests againstfracking and the Keystone XL pipeline; and in the emergence of Fight for $15. And the list goes on.

It was in this era of increased social unrest and grassroots organizing that the Sanders candidacy emerged, drawing its strength specifically from the economic justice movements within this larger activist landscape. And just as the Sanders campaign didn't arise in a vacuum, there's no reason to expect it will leave a vacuum behind it.

The "Powerful Impetus"

Grassroots struggles didn't disappear during the primary season, and neither did the issues that motivated them; we still need to fight for economic justice, for environmental justice and for an end to all forms of discrimination. The current struggles will continue and others will arise, assuming new and unpredictable forms -- possibly including a revived and more militant labor movement, if the April-May strike by Verizon workers is any indication.

But the grassroots struggles won't be the same as they were before the campaign.

We can, of course, expect that they will benefit from the addition of people drawn into activism by Sanders' message -- potentially millions of new activists -- but beyond that, both existing and emerging movements will be strengthened by the past year's broadening and deepening of political consciousness. One advance is a widespread realization that it's possible to think big, to be radical and demand what we want, not what we think our rulers might give. While the commentators touted incrementalism, Sanders won votes by insisting that requests for a half loaf only get us crumbs.

Another of the campaign's effects is a growing understanding that we are not alone, that we have many potential allies, despite persistent efforts by the politicians and the corporate media to divide us. If Sanders' massive rallies did nothing else, they brought activists from different struggles together in the same room, highlighting prospects for greater unity, mutual support and cooperation among the movements.

It's true that the likely influx of new, inexperienced supporters will mean new problems for grassroots organizers; longtime activists will have to exercise patience in orienting and educating the incoming recruits. But these are the problems we want to have. Our overriding concern now should be making sure that Sanders' voters don't sink back into apathy, that they stay in the struggle. The old Wobbly slogan is as timely as it was in the early 20th century: "

Don't mourn, organize!"

[David L. Wilson is working on a revised edition of The Politics of Immigration: Questions and Answers (Monthly Review Press, July 2007) with co-author Jane Guskin.]