The Case for More Government and Higher Taxes

https://portside.org/2016-08-04/case-more-government-and-higher-taxes

Portside Date:

Author: Eduardo Porter

Date of source:

The New York Times

It may be hard to remember, but Americans once appreciated the government that serves them. That's long gone.

Over the last six years, according to the Pew Research Center, four out of every five - or more - have said the government makes them feel either angry or frustrated. Last March, the ranks of the incensed included 78 percent of Bernie Sanders's supporters and a whopping 98 percent of those backing Donald J. Trump.

More than half of voters - including 61 percent of Mr. Trump's supporters - feel they are not keeping up with the rising cost of living. Three-quarters of Mr. Trump's supporters feel that life for people like them is worse than it was 50 years ago.

Some of this is caused by irreversible forces. The days when white men kept an uncontested hold on political power, when young adults without a college degree could easily find a well-paid job, are not coming back.

Yet it's not as if nothing can be done. These frustrated Americans may not fully realize it, under the influence of decades worth of sermons about government's ultimate incompetence and venality. But there's a strong case for more government - not less - as the most promising way to improve the nation's standard of living.

Last month, four academics - Jeff Madrick from the Century Foundation, Jon Bakija of Williams College, Lane Kenworthy of the University of California, San Diego, and Peter Lindert of the University of California, Davis - published a manual of sorts. It is titled "How Big Should Our Government Be?" (University of California Press).

"A national instinct that small government is always better than large government is grounded not in facts but rather in ideology and politics," they write. The evidence throughout the history of modern capitalism "shows that more government can lead to greater security, enhanced opportunity and a fairer sharing of national wealth."

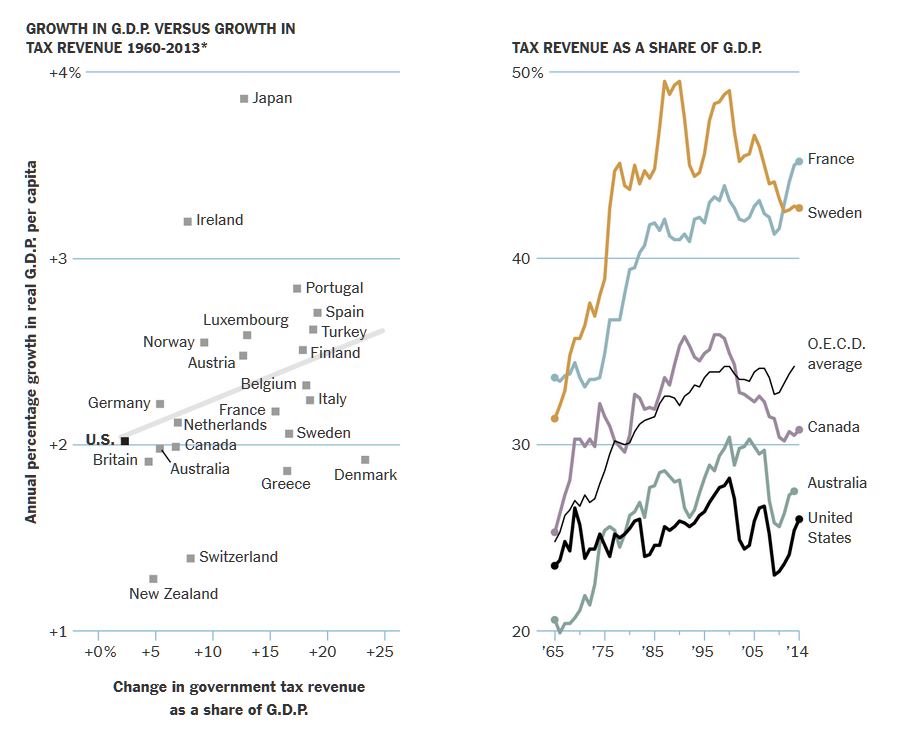

Growth and Government

Despite arguments that Big Government hinders economic activity, many countries where government has grown the most have also experienced stronger economic growth. Governments have grown across most industrialized nations - raising more taxes over time to offer more public services. In the United States, by contrast, the government remains virtually as small as it was 50 years ago.

Credit - New York Times

Sources: Jon Bakija, Lane Kenworthy, Peter Lindert and Jeff Madrick, "How Big Should Our Government Be?"; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

The scholars laid out four important tasks: improving the economy's productivity, bolstering workers' economic security, investing in education to close the opportunity deficit of low-income families, and ensuring that Middle America reaps a larger share of the spoils of growth.

Their strategy includes more investment in the nation's buckling infrastructure and expanding unemployment and health insurance. It calls for paid sick leave, parental leave and wage insurance for workers who suffer a pay cut when changing jobs. And they argue for more resources for poor families with children and for universal early childhood education.

This agenda won't come cheap. They propose raising government spending by 10 percentage points of the nation's gross domestic product ($1.8 trillion in today's dollars), to bring it to some 48 percent of G.D.P. by 2065.

That might sound like a lot of money. But it is roughly where Germany, Norway and Britain are today. And it is well below government spending in countries like France, Sweden and Denmark.

This agenda, of course, is more popular among liberals than conservatives. Economists on the right insist that higher taxes and bigger governments reduce incentives to work and invest, harming economic growth. In one study, the Nobel laureate Edward Prescott argued that the higher taxes needed to fund a bigger government discouraged Europeans from working.

WPA Federal Art Project

Michigan artist Alfred Castagne sketching WPA construction workers, 1939. (Image Number: 69-AG-410)

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

The conservative argument is hardly watertight, though. Another analysis found the decline in working hours in Europe was mostly because of tight labor market regulations, not taxes. Yet another suggests Europeans value free time more. Americans took the fruits of their rising productivity in money. Europeans took it in free time.

Here are some other things Europeans got from their trade-off: lower poverty rates, lower income inequality, longer life spans, lower infant mortality rates, lower teenage pregnancy rates and lower rates of preventable death. And the coolest part, according to Mr. Lindert - one of the authors of the case for big government - is that they achieved this "without any clear loss in G.D.P."

Even assuming that higher taxes might distort incentives, the authors concluded, negative effects are offset by positive effects that flow from productive government investments in things like health, education, infrastructure and support for mothers to join the labor force.

Europe's reliance on consumption taxes - which are easier to collect and have fewer negative incentives on work - allowed them to collect more money without generating the kind of economic drag of the United States' tax structure, which relies more on income taxes.

***Americans have long been more suspicious of a big, centralized government than Europeans have been, of course. But in recent decades, the nation's difficult racial divide has played a crucial role in checking the growth of public services. It is much easier to build support for the welfare state when taxpayers identify with beneficiaries. In multifarious America, race and other ethnic barriers stood in the way.

The American government pretty much stopped growing when the civil rights movement forced whites to share public space with blacks. Tax revenue as a share of the nation's economic output hit a peak in 1969 that it would not attain again until 1996, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

But for all the racial subtext to the election this year, times seem to be changing in unexpected ways.

No, Hillary Clinton has not suddenly become a radical. And Mr. Trump's grab bag of economic proposals is too self-contradictory to provide a sense of where he would land.

Yet the popular dissatisfaction that has brought us to this pass, across one of the most unusual presidential primary seasons in memory, could open new space to rethink the role of government in society.

Mr. Trump's supporters may not champion welfare. But they mistrust it less than your orthodox Republican. More of his supporters think the government should do more to help American families. More think corporate profits are too large. More think the economy is rigged to help the powerful. Fewer want to cut Social Security.

The ground is shifting under Democrats, too. In 1994, when President Bill Clinton was under siege from a Republican revolution about to take over Congress, 59 percent of Democrats said government was almost always wasteful. Last year, only 40 percent did. Then, 44 percent of Democrats said the poor had it too easy. Only 25 percent do today.

This does not mean, of course, that Big Government will get its day. For starters, small government Republican orthodoxy is likely to prevail in the House for years to come.

Still, a sense of opportunity is in the air. In "Wealth and Welfare States," published during the depths of the Great Recession, Irwin Garfinkel of Columbia University, Lee Rainwater of Harvard and Timothy Smeeding of the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggested the United States was ultimately likely to fall into line with the rest of the advanced industrial world - for the simple reason that they all face similar challenges.

"Long-term common problems and trends in rich nations are the fundamental driving forces in the development of welfare state institutions," they concluded. The United States' swing to the right since the 1970s might have moved it in the opposite direction for a while, but "all rich nations have large welfare states."

[Eduardo Porter writes the Economic Scene column for The New York Times. Formerly he was a member of The Times' editorial board, where he wrote about business, economics, and a mix of other matters.

Mr. Porter began his career in journalism over two decades ago as a financial reporter for Notimex, a Mexican news agency, in Mexico City. He was deployed as a correspondent to Tokyo and London, and in 1996 he moved to Sao Paulo, Brazil, as editor of América Economía, a business magazine.

In 2000, Mr. Porter went to work at The Wall Street Journal in Los Angeles to cover the growing Hispanic population. He joined The New York Times in 2004 to cover economics.

Mr. Porter was born in Phoenix and grew up in the United States, Mexico and Belgium.]