When Librarians Are Silenced

Search the Internet for news stories about public libraries in America and chances are that, sooner or later, the phrase “on the front lines” will come up. The war that is being referred to, and that libraries have been quietly waging since the September 11 attacks, is in defense of free speech and privacy—two concepts so fundamental to our democracy, our society, and our Constitution that one can’t help noting how rarely their importance has been mentioned during the current election cycle. In fact quite the opposite has been true: Donald Trump has encouraged the muzzling of reporters and the suppression of political protest, while arguing that government agencies aren’t doing enough spying on private citizens, especially Muslims. Hillary Clinton has failed to be specific about what she would do to limit surveillance, while her running mate,Tim Kaine, has promised to expand “intelligence gathering.” Meanwhile, public libraries continue to be threatened by government surveillance—and even police interference.

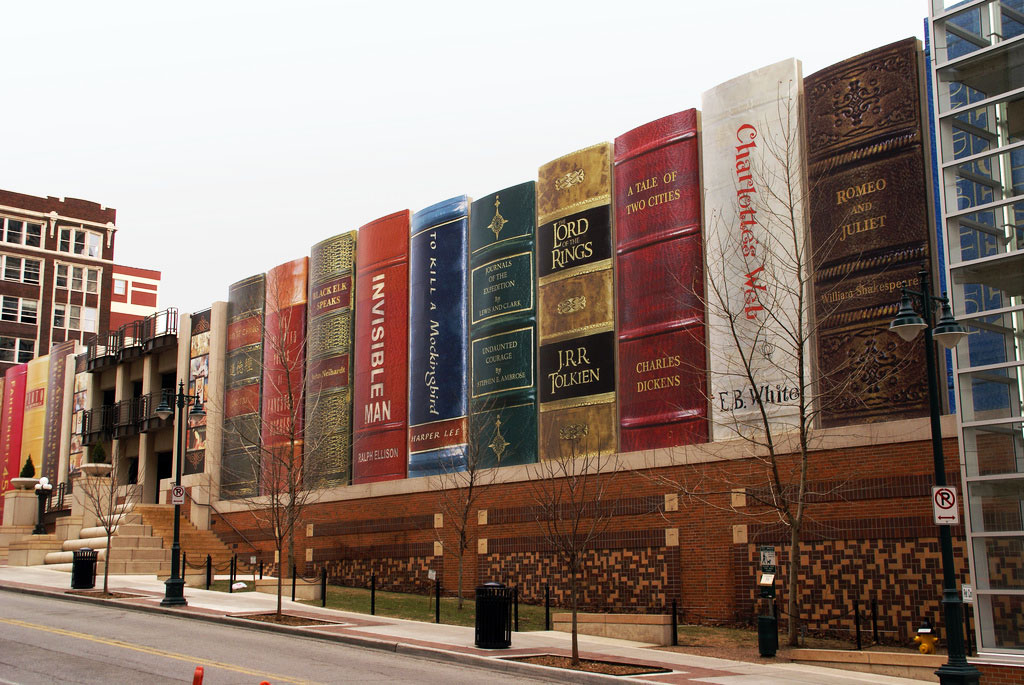

In the most recent such incident, a librarian in Kansas City, Missouri was arrested simply for standing up for a library patron’s free speech rights at a public event featuring a former US diplomat. Both the librarian and the patron face criminal charges. The incident took place last May, but went largely unnoticed until several advocacy groups called attention to the situation at the end of September. In cooperation with the Truman Presidential Library and the Jewish Community Foundation of Greater Kansas City, the Kansas City Public Library had invited Dennis Ross—a former advisor on the Middle East to Presidents George H.W. Bush and Barack Obama, and to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and currently a distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy—to speak about Truman and Israel at its Plaza Branch. The library hosts between twelve and twenty speakers each month, and though some of the topics and speakers have been controversial, the events have always been peaceful.

As a matter of policy, the library declines to hire outside security guards. But because of a recent, traumatic event in Kansas City—in April 2014 a lone gunman attacked the Jewish Community Center and a Jewish retirement home, killing three people—the library administration agreed that three local off-duty policemen and Blair Hawkins, a former Seattle police officer now serving as Head of Security for the Jewish Community Foundation, could be present. According to the library, as part of the agreement nobody was to be prevented from asking a controversial question and the security team would consult with library officials before ejecting any nonviolent patrons. At the Dennis Ross event, audience members had their bags searched as they entered the library.

During the question-and-answer session after Ross’s address, a local writer and activist named Jeremy Rothe-Kushel asked about US support for what he called Israel’s “state-sponsored terrorism.” Ross answered, and when Rothe-Kushel followed up with a more aggressive question, Hawkins and one of the other guards approached him and immediately tried to eject him from the building—despite the fact that Rothe-Kushel posed no danger to the speaker or audience members. One of the guards, Brent Parsons, shouted—incorrectly—that Rothe-Kushel was at a private event. Later Parsons added, “This is private property.” It is revealing that a policeman should have imagined, even in a heated moment, that a public library was private property.

As the guards grabbed Rothe-Kushel, Steve Woolfolk, the library’s director of programming, who had been watching from off stage, interceded on Rothe-Kushel’s behalf and defended his right to remain in a public building and ask questions at a public forum; in a cell phone video, Rothe-Kushel can be heard saying, “Ask me to leave I will leave.” The guards led Woolfolk and Rothe-Kushel through the green room toward the lobby. As Woolfolk rounded a pillar, several of the guards grabbed Woolfolk from behind. Woolfolk was kicked in the leg (resulting in a torn knee ligament), slammed against the pillar, and thrown into a chair. When he bounced out of the chair onto the floor, the guards forced him back into the chair, and handcuffed him. Both men were arrested by a uniformed police officer who had been summoned by Hawkins. Rothe-Kushel was charged with trespassing and resisting arrest, and Woolfolk with interfering with an arrest. Meanwhile, in the auditorium, the program continued; Ross answered a few more questions.

Since May, the cases against both men have been pending. Cellphone and security videos corroborate Rothe-Kushel’s and Woolfolk’s version of events. Whether or not one agrees with the implications of Rothe-Kushel’s question, he posed no physical threat to either Ross or the audience, and was simply trying to speak. Woolfolk remained reasonable and polite. The guards’ rapid recourse to shouting and to physical violence to detain Rothe-Kushel and Woolfolk did not seem to have a basis other than that the guards were nervous in the presence of a former top US official and that Rothe-Kushel was a local activist who was well-known for asking confrontational questions at public events. On entering the library, Rothe-Kushel had been identified by Hawkins and subjected to a more thorough search than had the other patrons. The off-duty police acting as guards seem to have been confused about the exact nature of their duties—and about where they were.

The arrests went unmentioned in the national press, in part because of the library officials’ hope that the incident—which Library Director Crosby Kemper III has described as an “overreaction”—would simply blow over and the charges against Woolfolk and Rothe-Kushel dropped. The case gained new attention, however, in late September, when the library drew support from the American Library Association and the Bill of Rights Defense Committee. (Over the years the American Library Association’s position has been that freedom of speech—and our right to information—is absolute and indivisible, regardless of the nature of that speech and the content of that information. In 2003, the ALA went to the Supreme Court in an unsuccessful attempt to reverse the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which requires that publically funded libraries install filters to screen out material that might be considered obscene or unsuitable for children.) On October 5, the Forward published an article criticizing the security guards’ behavior, and this week, a local newspaper, The Pitch, has raisedquestions about the off-duty police officers involved in the case.

For a while, library officials hoped that an accord might be reached between the library and the prosecutor’s office; if the defendants agree to refrain from filing a civil suit, the charges against them will most likely be dropped. But the prosecutor’s office has announced that it (in co-operation with Hawkins’s employer, the Jewish Community Foundation) will go forward with the cases against the both the librarian and the patron.

Whatever the outcome, the case adds to a growing history of attacks on libraries—simply for upholding the bedrock values that have historically made them so important. Originally passed in 2001 and since reauthorized and amended, the USA PATRIOT Act—in particular its section 215—has given the FBI the power to request library borrowing records, patron lists, computer hard drives and Internet logs. In a speech in 2003, then Attorney General John Ashcroft claimed that the understandably concerned librarians were suffering from a “baseless hysteria,” repeating the word “hysteria” several times.

Two years later a group of Connecticut librarians (who came to be known as ”the Connecticut Four”) resisted a government request to turn over the names and online activity of everyone who had used a certain library computer; the librarians were served with a gag order forbidding them to discuss the case. After their situation attracted the attention of the ACLU, the gag order was rescinded by the FBI in 2006; the following year, the Connecticut Four received the Paul Howard Award for Courage.

In 2005, Joan Airoldi, a librarian in rural Washington State, received the PEN/Newman’s Own First Amendment Award for defying an FBI demand for a list of patrons who had borrowed a biography of Osama bin Laden. And just two weeks ago, four off-duty policeman from the Grandview Police Department (working part-time as security guards at another Kansas City library, the Mid-Continent Library) objected to that library’s decision to put up a display case entitled “Black Lives Matter— Books About African American Experiences” and featuring novels by Toni Morrison and others. Even after the library agreed to adjust the exhibit sign’s language to read “Books about Black Lives—The African American Experience,” two of the four officers resigned in protest.

Part of what’s disturbing about both Kansas City incidents is the extent to which they illustrate the gap that has opened between police and the communities in which they work—a divide that, with horrifying regularity, produces far more disastrous and violent results in our inner cities. In fact, public libraries are among the very few remaining places where all Americans can meet to exchange ideas and listen to opposing viewpoints for free.

According to the Libraries for Real Life Project, an organization founded within Wisconsin’s South Central Library System, 68 percent of Americans have library cards. Americans borrow more than two billion items from libraries every year. Anyone can go to a public library (again, for free) to learn computer skills and apply for jobs. Immigrants can receive help in obtaining green cards and passing citizenship tests, and can learn and practice English. Senior citizens can find out how to take advantage of their social security benefits, and children can attend story hours and early-reading classes. And at least partly because of their own experience with government surveillance, libraries all over the country have begun to conduct workshops designed to teach patrons how to protect their privacy online.

I spent some of the happiest times of my childhood in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza Library, which now, like many libraries, has expanded its services in response to the needs of the communities it serves. Along with eleven other Brooklyn libraries, it has created rooms in which the families of prisoners (especially those who cannot afford to visit their incarcerated relatives) can chat with them via video conferencing; in the same rooms with the monitors and cameras are children’s books, and during these “televisits,” prisoners are encouraged to read books with their kids. On October 29, again at the Grand Army Plaza library, a group of actors will perform a little known and especially violent Euripides play, The Madness of Hercules, and use it as the jumping-off point for a discussion of gun violence; the audience of several hundred will include local schoolchildren and members of the New York City police department.

The right to read, to think, to discuss and listen to ideas in a public forum is essential to an open society, as is our individual privacy. One hopes that the Kansas City case—only the most recent of many—will be resolved without further cost, trouble and damage, and that librarians there and everywhere will be able to do their jobs without taking on the added burden of battling for our freedom.

[Francine Prose is a Distinguished Visiting Writer at Bard. Her new novel, Mister Monkey, will be published later this month. (October 2016)]