Martin Luther King, Institutions and Power

When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, he was in Memphis, supporting striking sanitation workers. By that time in his crusade for racial justice, he had elevated full employment to a key plank in his platform. The full name of the March on Washington was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. A common placard held up that day read, “Civil Rights Plus Full Employment Equals Freedom,” a powerful economic equation indeed.

In my experience, too few people remember this aspect of King’s movement, instead emphasizing his stirring spiritual commitment to racial inclusion. But King was of course thoroughly versed in the reality of the institutional barriers blocking blacks and his unique genius was to combine deep spiritual awareness with an equally deep understanding of the role of power in economic outcomes. That’s one reason he was in Memphis, supporting the union.

In 1967, King called for “a radical redistribution of economic and political power.” He particularly understood the power, for better or worse, of American institutions, most notably of course, the institution of racism, which so successfully blocked African Americans from decent homes, jobs, schools and opportunities.

But countervailing institutions existed within his vision as well, including the church and the union, and, if it could be forced to live up to its promise, the government. Even the institutions of the consumer economy and the job market could, with the right force and strategy, including boycotts that flexed black consumer muscle and equal opportunity laws, be nudged in the direction of racial justice.

To some readers, this “institutional” framework may be confusing. What do I mean by referencing the consumer or job markets or racism or unions, as “institutions”? This certainly doesn’t square with the classic economic explanation of how the economy works: profit-maximizing individuals achieving optimal social welfare by each individual pursuing their goals.

The institutional framework, with its emphasis on historical, legal and cultural practices (norms) embedded in economic systems, stands in stark contrast to the market forces framework. Surely no one could question whether the legal system or the housing market black people faced in King’s time, not to mention our own, promoted objective, blind justice. Discrimination in schools, the economy, and almost every other walk of life could not and cannot possibly be viewed as a fair or merit-based system.

Honoring King’s vision and legacy thus requires not simply remembering his most well-known dream: a racially inclusive society very different from the one that existed in his, or sadly, our own time. It requires recognizing the need to redistribute the power from the oppressive, exclusionary institutions, many of the same ones — housing, schools, criminal justice, the economy — he fought for until the day he was taken from us.

What does honoring that vision mean today?

Although I certainly don’t advocate giving up on President-elect Donald Trump’s administration before it has started, all signs suggest that it and the Republican-led Congress will hurt, not help, the economically less advantaged. Republican budgets threaten to undermine the safety net, Trump’s proposed tax policy squanders fiscal resources on tax cuts for the rich, undermining opportunities for those stuck in places without adequate educational or employment opportunities. There’s talk among Republicans of trying to get more states to pass “right to work” laws that undermine unions and cut workers’ pay. Listening to Ben Carson’s hearing for secretary of housing and urban development quickly disabuses one of hope that he’ll tackle the legacy of segregated housing that remains a serious problem. As far as reforming the institutionalized racism the remains embedded in our criminal justice and policing systems, again, it’s awfully hard to be hopeful.

There are, however, many levels of institutional norms, laws and practices. The Fight for Fifteen has been immensely successful in raising minimum wages at the state and sub-state levels. I can’t prove this, but I’d bet that without Black Lives Matter, there would be no “blistering report” from the Justice Department on the racial practices of the Chicago Police Department. The activist group “Fed Up” has had great success elevating the issue of economic justice as regards Federal Reserve policy, a policy area that even liberal presidents have avoided getting into.

As I recently wrote regarding “ban the box,” a policy designed to give job-seekers with criminal records a fairer shot at employment:

Nineteen states and over 100 cities and counties have already taken similar action for government employees, and seven states (Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon and Rhode Island) plus Washington, DC and 26 cities and counties have extended ban the box policies to cover private employers. Some private businesses, including Walmart, Koch Industries, Target, Starbucks, Home Depot, and Bed, Bath & Beyond, have also adopted these policies on their own.

This last part about the private businesses is instructive. The Selma bus boycott was, of course, in no small part an economic action: Black people would not pay for discrimination. Regarding full employment, King realized that at high levels of unemployment, it’s costless to discriminate against a significant swath of potential workers. But when the job market tightens up, discriminating against a needed worker means leaving profit on the table.

Especially in the age of Trump, when so many Americans feel as if representative democracy is seriously on the ropes, it seems a no-brainer to channel King and once again tap the power of boycotts and leaning on businesses to do the right thing. It makes no sense at all to cede this field to Trump as he nonsensically claims (and gets) credit for job creation that already was happening.

My intuition is that many businesses, as in the ban-the-box example, would be willing to help push back on the institutional injustices that persist. Higher and more equal pay scales, implementation of the updated, higher overtime threshold that was wrongly blockedby a Texas judge (in fact, many businesses, to their credit, have gone ahead with this change), not blocking collective bargaining if their workers want to exercise that right, flexible scheduling policies that help parents balance work and family — there’s no reason for progressives not to fight for these ideas at the sub-national level and the private sector.

Although these sub-national fights are more likely where the action is for the next few years, meaningful action is developing at the national level as well. King would have easily recognized the Trump phenomenon as the work of exclusive institutions once again grabbing the power and would have organized accordingly and effectively. As we speak, many of us are trying to block the repeal of health-care reform in this spirit. The Indivisible Movement and the Women’s March would also have been highly familiar to Dr. King.

But on whatever level or in whatever sector the fight takes place, as we celebrate King’s indelible contributions, let us recall his understanding of power, the institutions that power supported and his admonitions to us not to rest until much more of that power lies in the hands of those who still command far too little of it.

[Jared Bernstein, a former chief economist to Vice President Biden, is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and author of the new book 'The Reconnection Agenda: Reuniting Growth and Prosperity.' Follow @econjared ]

I noted that Dr. King became increasingly committed to full employment—the slide below is from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—as evidence developed in the 1960s and 1970s was beginning to show the importance of very tight labor markets for African-Americans.

Source: History.com

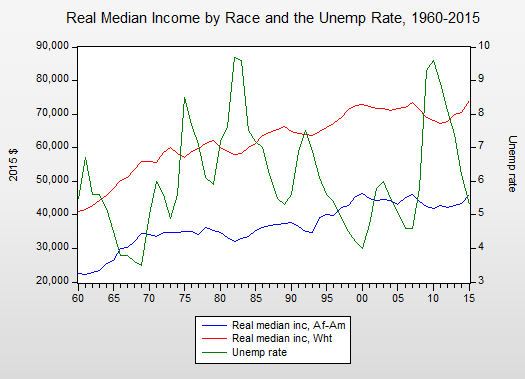

Here’s a bit of empirical backup. The first figure shows the Census Bureau’s series of black and white real median family incomes against the unemployment rate. The cyclicality of the series is evident, but there are only a few episodes wherein very low unemployment persisted for a few years: mainly in the 1960s and 1990s, periods associated with rising median incomes for blacks and whites.

Sources: Census, BLS

In fact, a simple regression of the log change in real black median income on a flexible specification for the unemployment rate (at t, t-1, and squared) explains 39 percent of the variance in the dependent variable (results for whites are similar), more than you might expect given the fact that income formation is a pretty complex phenomenon.

Read more here.