'Day Without Immigrants' Protests Close Restaurants Across the US

Diners in cities nationwide were greeted by locked doors at many of their favorite restaurants Thursday, along with signs in the window expressing solidarity with striking workers participating in a #daywithoutimmigrants protest.

Immigrants didn’t go to work to show their impact on the economy, and some restaurants showed solidarity by shutting down their kitchens, or even their entire business.

The action was part of a growing movement of strikes and boycotts intended to demonstrate displeasure with the Trump administration and its policies – through the economy. According to Maria Fernanda Cabello, an immigration activist and Daca recipient, Thursday’s action was a demonstration that “immigrants are ready to show their power on the streets”, in anticipation of holding even larger events in the coming months.

“Through non-cooperation of our labor and by not purchasing we’re just making a really bold statement that this country is sustained by us,” Cabello said.

Immigrants rights organizations aren’t the only ones organizing around these types of economic and service disruption protests. Earlier this month, Yemeni grocery stores closed throughout New York City in protest of Trump’s travel ban executive order. On Friday more than 80 locations nationwide are hosting events aimed at building towards “a series of mass strikes”, with participants staying home from work and school, and not spending any money at businesses.

“We need to be able to show our power and one of the ways we do that historically, both in this nation and many other countries, is through our job and our workplace, and sometimes taking back our work,” said Todd Wolfson, one of the lead organizers of Friday’s #Strike4democracy.

Organizers see the day as a “preview” of an even larger mass strike planned for March. That action, billed as “a day without women” by organizers, is a follow up of the massive women’s march protest movement that brought millions into the streets the day after Donald Trump was inaugurated.

The idea of a general strike as a means of expressing political or social dissatisfaction is fairly novel in the US. Labor experts cite the 1919 Seattle general strike as the last such demonstration, but even there workers were at least as motivated by ordinary union concerns about wages and workplace conditions as they were about sending a broader political message endorsing socialism.

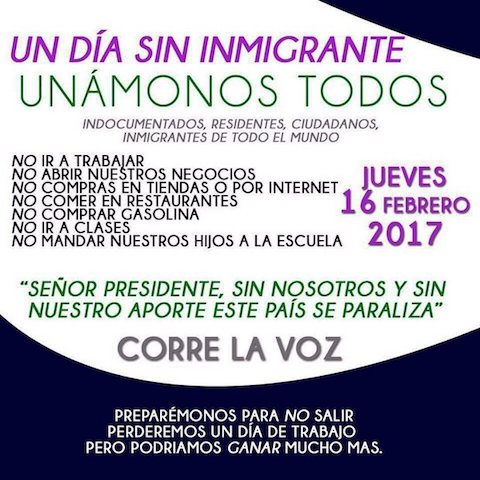

Electronic fliers like this one circulating on What's App were a major driver of participation in the day's strike, which was not centrally coordinated by any organization. Composite: Maria Fernanda Cabello

The tactic has been used in other countries regularly since the industrial revolution with varying degrees of success. India and France have both seen large scale general strikes in the past eight years, but even these were primarily orchestrated by public sector workers whose connection to to the government is more direct than private sector workers.

The prospect of a primarily political general strike in the US is, for all intents and purposes, unprecedented. New York University social and cultural analysis professor Andrew Ross said that during Occupy Wall Street there were some intimations towards a general strike, but a lack of buy-in from establishment labor unions stifled the effort before it got off the ground.

“One strong interpretation of that is that Occupy was a very horizontal type movement … Most trade union organizations are highly hierarchical and they didn’t necessarily want their members catching the Occupy bug,” Ross said.

Without full throated support from major trade and industrial unions, general strikes face an uphill challenge in gathering enough leverage to affect the economy and send a loud message. Workers who strike under these circumstances also face a higher likelihood of losing their job for missing work. Still, Gary Chaison, a professor of industrial relations at Clark University said the right strikes at the right time, even without dramatically high numbers of participants, can be effective in the right industries.

“Rolling strikes, also called rotating strikes, have proven effective among flight attendants and pilots – groups of workers who are difficult to replace if they strike. They have also proven effective in the $15/hour minimum wage movement among fast food workers, a case in which a few workers out can close an entire store. So the effectiveness of rolling strikes would depend on ‘strategic location’. A few workers on strike here or there can shut down an entire operation,” Chaison said.

Although the Friday event has been dubbed a “general strike”, Wolfson said he doesn’t yet expect it to reach single-day critical mass.

“It’s a fine imagination for us to hold, but I think we need to be really honest about where this country is and what we’re ready for. It is a seedling towards that though.”

Cabello, who is helping to organize what she hopes will be a larger day without immigrants on 1 May or “May Day”, an internally recognized day of labor activism and celebration, said the purpose of the day without immigrant strikes is to “move the conversation from ‘are immigrants wanted’ to ‘are immigrants needed’”.

There are more than eight million undocumented immigrants in the US workforce, and they make up a disproportionate number of workers in several industries, including construction and food services.

“‘A Day without Immigrants’ would take a great deal of organizing and coordination to gain worker participation but would provide real proof to the public of the critical role that immigrants play in our economy as workers,” said Chaison.

Cabello admits it will be difficult, but said she sees no shortage of enthusiasm among immigrant communities for getting involved in this type of direct action. “A lot of immigrants get it and feel like ‘I might loose some money but what I can get in exchange could be worth so much more than a week of my wage’.”