What Is Single-Payer Healthcare and Why Is It So Popular?

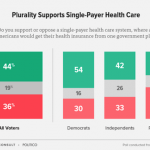

As the United States grapples with the future of the Affordable Care Act, the notion of a single-payer healthcare system to simplify and expand coverage is being discussed more and more. According to a recent poll by the Morning Consult and Politico, 44% of Americans favor a single-payer healthcare system.

But what exactly is single-payer healthcare?

Single payer—or Medicare for All, as it's sometimes referred to in the U.S.—is a system in which all healthcare financing is provided by one entity, such as (but not always) the federal government. All residents receive core coverage regardless of income, occupation, or health status.

The U.S. is one of the only countries in the developed world that does not have such a system in place, but in other countries like Canada and England, the care itself is still provided by private organizations and doctors. But that care—everything from hospital visits to prescription drugs to mental health care—is covered for all residents by the state, via taxes determined by the state. In other words, public financing pays for private care.

In recent years, the idea for a single-payer plan in the U.S. has been discussed, most notably by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders during his 2016 presidential campaign. Under his plan, co-payments, deductibles, and other cost-sharing measures would disappear.

Around 95% of households would save money under this system, according to Gerald Friedman, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and one of the architects of Sanders' plan. In 2013, Friedman's research found that a single-payer plan would save the U.S. about $592 billion in 2015 with savings growing over time, largely by cutting administrative billing costs and reducing pharmaceutical prices.

How It's Different from the Current System

Healthcare financing in the U.S. is an often complicated web of hospitals, doctors, and other care providers, middlemen like insurance and pharmaceutical companies, and public programs like Medicaid, Medicare, and state-run marketplaces. As many Americans know, it's incredibly confusing and expensive for most parties involved. (According to Friedman's report, Americans spend nearly four times as much on billing and insurance-related activities as doctors in Ontario do, where a single entity is in charge of billing and repayments.)

And if you're under 65, your health coverage is largely dependent on your, your parents', or your partner's employment status, though the Affordable Care Act has made it slightly easier to gain independent coverage.

Single payer would simplify all of this by largely cutting out the insurance and pharmaceutical companies and untethering coverage from your job. The losers are those middlemen, like private insurance companies, that make the current system so frustrating to navigate and politically fraught. Also, much to the dismay of the wealthiest households, their taxes would increase the most of any group.

But the working middle class—people who make too much money to qualify for Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act coverage subsidies—would benefit greatly, as would an employer's HR department. "Employers spend a lot of money processing information for the insurance industry, identifying insurance plans, and negotiating," says Friedman. "And that would just disappear." Instead, the government (or the individual states, depending on how the logistics shake out) would negotiate prices, set plans, and deal with the paperwork.

Everything from dental care to long-term care is covered for everyone under single payer, equalizing treatment between the affluent and less affluent. If this sounds familiar, it's because there is already a fairly successful public medical financing system in the U.S.: Medicare, which all seniors over 65 can qualify for. Proponents of single payer point to Medicare, which is fairly popular, as an indication that a generalized universal program could work here.

How It's Paid For

Federal funding currently earmarked for healthcare, including spending for Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which totals in the trillions of dollars, would be used for the new system.

Following Sanders' plan, that leaves about 30% of the needed funding unaccounted for, says Friedman, which would need to come from new or increased taxes. He advocates a progressive tax system, i.e., the wealthiest households would pay significantly more, through an increased personal income tax and taxes on unearned income, like capital gains and dividends.

But he notes you can also raise money through less progressive means, like a consumption tax, or a tax on goods and services. "If Trump came out in favor of single payer, then I suspect he would fund it with a consumption tax," he says. That would still impact wealthier households more than lower and middle class households.

How It's Done Elsewhere

Despite being lumped together under the single payer moniker, healthcare systems in other developed countries differ, but have some commonalities: They provide universal coverage, and provide a baseline of care.

The National Health System in the United Kingdom, for example, covers everything from routine screenings to long-term care to end-of-life care. In Australia, there is a universally available public healthcare option and a private healthcare system. But all residents in both countries have insurance, as do residents in other countries across Europe.

Jonathan Oberlander, a professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, argues that advocates of the system in the U.S. typically point to the Canadian system as a good model, "where all legal residents in each province or territory receive coverage from one government insurance plan for medically necessary hospital and physician services." You can buy supplemental insurance if you wish, but there's a minimum, fairly comprehensive plan for everyone. This is similar to Medicare, but covers an even larger percentage of the costs than Medicare does for American seniors.

It's not a perfect system. "All countries struggle with tensions among cost, access, and quality; at times, Canada has grappled with fiscal pressures, wait lists for some services, and public dissatisfaction," writes Oberlander. "Yet its problems pale in comparison to those in the United States."

Still, he writes the single-payer model faces an uphill battle here: Political pressure, the unpopularity of tax increases of any kind, and robust business interests have long hampered its implementation.