Arkansas Judge Moves to Block Executions

A judge in Arkansas moved Friday to block the state from carrying out up to seven executions this month, deepening the turmoil that surrounds a planned pace of killing with no equal in the modern history of American capital punishment.

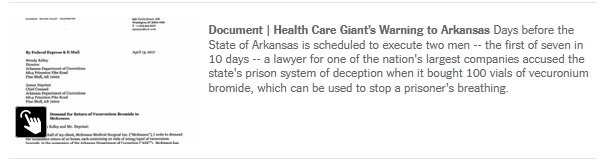

Judge Wendell Griffen of the Pulaski County Circuit Court issued a restraining order Friday that forbids the Arkansas authorities from using their supply of vecuronium bromide, one of three execution drugs the state planned to use. Hours earlier, the nation’s largest pharmaceutical company went to court to argue that the state had purchased the drug using a false pretense.

The judge scheduled a hearing for Tuesday morning, about 14 hours after the state had intended to carry out its first execution since 2005. The Arkansas attorney general’s office said the state would appeal the judge’s ruling, which threatened to derail a plan that once called for eight executions over the course of 10 days.

The restraining order surfaced during an afternoon and evening of legal chaos: The State Supreme Court issued a stay of execution for one death row prisoner, and a federal judge was also weighing a request to block the executions. Yet Judge Griffen’s order appeared to have the widest immediate effect, and it was the first to focus on the misgivings of the pharmaceutical industry.

Four companies have publicly raised concerns about how the Arkansas Department of Correction came to stockpile the drugs for its lethal injection cocktail — midazolam, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride — but only the McKesson Corporation, the drug distributor that ranks fifth on the Fortune 500 list of companies, made an explicit allegation of deception.

Arkansas, the company said, bought 10 boxes of vecuronium bromide, which the state can use to stop a prisoner’s breathing.

But the state prison system “never disclosed its intended purpose to us for these products,” a lawyer for McKesson, Ethan M. Posner, wrote in a letter obtained by The New York Times. “To the contrary, it purchased the products on an account that was opened under the valid medical license of an Arkansas physician, implicitly representing that the products would only be used for a legitimate medical purpose.”

The company confirmed the authenticity of the letter, which Mr. Posner sent on Thursday to two Arkansas officials. By Friday night, the company had persuaded Judge Griffen to intervene. Spokesmen for Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, and the prison system did not respond to requests for comment about the dispute.

The state had scheduled two executions for Monday night. The state also planned to carry out double executions on April 20 and April 24, as well as one on April 27. (An eighth execution was stayed by a federal judge.) All of the condemned prisoners are challenging their executions.

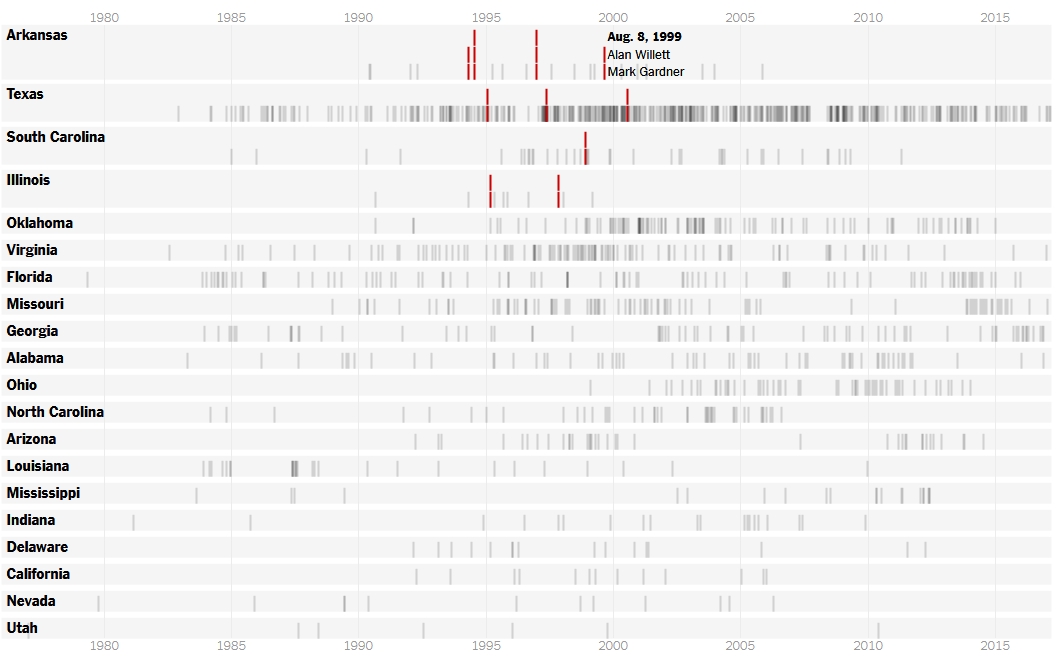

Executions by day of 20 states with the most executions Red represents multiple executions in a day

Arkansas originally planned to carry out eight executions in 10 days. No state has tried to execute so many people in such a short period. Virginia is the only other state with an execution scheduled this month.

Although the pharmaceutical industry has long expressed misgivings about how state prison officials can use its products, there is limited precedent for such a pronounced rupture between a state and drug companies.

On Thursday evening, two manufacturers, Fresenius Kabi USA and West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corporation, asked Judge Baker to block the state from using any of their products in the executions. The companies said they had “learned of information suggesting that medicines they manufactured might be used in lethal injections in Arkansas.”

Arkansas’s possession, while West-Ward said it appeared that it had produced the state’s midazolam stock.

“The use of the medicines in lethal injections runs counter to the manufacturers’ mission to save and enhance patients’ lives, and carries with it not only a public-health risk, but also reputational, fiscal and legal risks,” the companies wrote in a friend of the court brief.

The companies said the state seemed to have obtained its products despite efforts to keep the drugs from the country’s execution chambers.

For its part, McKesson took legal action against Arkansas in connection with an episode that, Mr. Posner’s letter suggested, has been the subject of quiet wrangling for about nine months.

According to the company’s lawyer, McKesson filled the state’s order for vecuronium bromide in July. Less than two weeks later, McKesson and the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, became concerned about the sale, and the state agreed to return the drugs in exchange for a refund, Mr. Posner wrote.

The company processed the refund and provided the state with a prepaid shipping label, according to the lawyer, but the state never returned its drug supply, insisting it be offered a substitute product.

Arkansas, Mr. Posner wrote, “never disclosed its intended purpose for these products, even though it knew full well that the manufacturer does not permit sales of vecuronium bromide to correctional facilities.”

Mr. Posner noted that the state was a longtime McKesson customer, buying items like stethoscopes and surgical gloves, and that Arkansas’s vecuronium bromide order had been shipped to the same administrative address as other orders.

Pfizer, which is among the drug companies that have moved to prevent its products from being used for lethal injections, said that the sale was “in direct violation of our policy” and that the company had twice asked Arkansas to return its products.

“In addition, we considered other means by which to secure the return of the product, up to and including legal action,” the company said in a statement. “After careful consideration, we determined that it was highly unlikely that any of these means would secure the timely return of the product and thereby prevent this misuse.”

McKesson had warned Arkansas officials that it would “take all appropriate action” if the state defied a Friday deadline to return its products, but it was unclear whether it or any of the other companies would succeed in the courts or elsewhere.

“In the context of executions, we have never seen a clawback,” said Megan McCracken, who specializes in lethal injection litigation at the law school of the University of California, Berkeley.

Drug manufacturers and distributors, she noted, were plainly “acting in their own interests for their business interests, their investors and their public images.”

But some people still welcomed McKesson’s apparent resistance to Arkansas officials.

“McKesson is acting to prevent a grave misuse of lifesaving medical products, and to protect the systems and contracts the company established to stop the sale of drugs to death rows,” Maya Foa, director of Reprieve, an international human rights group that works with drug companies, said in a statement.

She added: “Arkansas has made concerted efforts to undermine the wishes and interests of responsible health care companies, violating the law and putting public health at risk. McKesson is right to fight back against these duplicitous and dangerous practices.”

Fresenius Kabi said it had sent at least three letters to state officials since last July.

“Our records indicate no sales of potassium chloride — directly nor through any of our authorized distributors — to the Arkansas Department of Correction,” the chief executive of the company’s American subsidiary, John Ducker, said in a recent letter to Mr. Hutchinson. “So we can only conclude Arkansas acquired our products from an unauthorized seller.”

The governor, a company spokesman said, never replied.