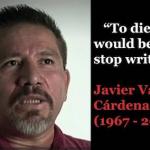

The Death of a Mexican Journalist Who Said No to Silence

It happened in broad daylight. On Monday, journalist Javier Valdez Cárdenas was driving near his office in Culiacán, the capital of the northern Mexican state of Sinaloa — the land of the Sinaloa Cartel and its former kingpin Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán Loera.

Around noon, Valdez was forced from his red Toyota Corolla and shot more than a dozen times, according to Zeta, the Tijuana-based newsweekly. Valdez was left face down in the street, his signature straw hat still on.

He had also just filed his final article, about a protest in Culiacán against the deadly attacks teachers face by traveling and working in some of Sinaloa’s most dangerous areas. At least six teachers have been killed in the state so far this year.

Valdez is the sixth journalist murdered in Mexico in 2017. Since 1992, 40 journalists have been killed in the country for their work, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists — 32 of them with impunity. The Mexican government's own National Human Rights Commission counts at least 125 journalists killed in the country since 2000. The death toll makes Mexico one of the most dangerous places in the world for reporters.

Juan José Rios, Sinaloa’s state prosecutor, said authorities were investigating Valdez's murder.

Whatever the motive, his death is "a blow for the journalist community here," said Paulina Villegas, a Mexico City-based reporter with The New York Times.

Valdez's killing also adds to demands that Mexico’s government do more to protect press freedom. In April, CPJ met with Mexico’s president, Enrique Peña Nieto, to pressure his administration to make press freedom and the protection of journalists a higher priority. Earlier this month, the government appointed a new prosecutor to investigate crimes against the media. Of more than 800 cases of attacks on journalists in the past six years, "only two of them have resulted in convictions," said Villegas.

Further, collusion between local authorities and criminal groups is common. In this video, investigative journalist Marcela Turati calls for criminal investigations to examine ties between murdered journalists and politicians and to "not just blame the cartels".

On Tuesday, reporters across Mexico expressed outrage at the murder of yet another colleague. Vigils were held in the state of Veracruz, where several journalists have been murdered in just the past year.

"The feeling is if someone like him can get killed, even after 20 years of reporting crime, then what's the hope for all of the other unknown and starting-up journalists around the country?" says Villegas.

Valdez’s family, his wife and two children, also held a memorial service in Culiacán.

Several media outlets in Mexico also ceased publication for a day, including Animal Político, a popular news site based in Mexico City.

In Miami, Univision staff worked under a large projection of a photo of Valdez.

Among the mourning is journalist Turati, from Mexico. She called Valdez a friend, and remembered him for his sense of humor, “always happy, joking, even in the bad moments.” He was also "devoted to his family and talked a lot about his children," Turati said.

"He was like our older brother," she said of Valdez, who turned 50 years old in April.

For years, many journalists heading to report in Sinaloa considered it a must to meet with Valdez — for a beer, for guidance on reporting on organized crime, for "strategies to stay alive," as Turati put it. He was prolific when reporting on violence in his home state. He wrote for the Mexican national daily La Jornada and contributed to the AFP news agency. Valdez also wrote books, including “Miss Narco,” “Los Morros del Narco” ("Narco Youth") and “Narcoperiodismo” ("Narco Journalism"), about how “narco culture shaped life around him,” said Turati. In January, an English-language collection of his stories was published, titled “The Taken: True Stories of the Sinaloa Drug War.”

But Valdez made one of his biggest marks in 2003. That's when he co-founded Ríodoce, a regional newsweekly, for which he also wrote a column called “Malayerba” (slang for “bad weed”). It was known for chronicling how poverty and organized crime play out in everyday life.

“This is a war, yes, but one for control by the narcos, but we the citizens are providing the deaths, and the governments of Mexico and the United States, the guns. And they, the eminent, invisible and hidden ones, within and outside of the governments, they take the profits.”

At times, Ríodoce angered the powerful and dangerous. It is one of the few remaining news outlets in Sinaloa not dependent on government advertising, and it is respected for its coverage of crime and corruption in Mexico’s north. In 2009, a grenade was set off at the newsweekly’s office and, in 2011, the publication was forced offline for several days after a denial of service (DOS) attack.

This year, Valdez alerted Article 19, a press freedom group, that an armed group had purchased massive amounts of a late February edition of Ríodoce. It remains unclear which article, in particular, they were trying to bury.

But Valdez refused to be silenced when it came to reporting on violence and corruption, joining other Mexican reporters determined to investigate and publish on the subject despite the dangers. "He said he had to talk and write about it because if nobody does it will be worse," said Turati. "He felt it was his duty."

“The youth will remember this as a time of war. Their DNA is tattooed with bullets and guns and blood, and this is a form of killing tomorrow. We are murderers of our own future.”

For that, he was recognized within Mexico and internationally. In 2011, Valdez received an International Press Freedom Award from the CPJ. He traveled to New York City, donned a tuxedo, and attended the organization’s annual ceremony in a ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. “I have been a journalist these past 21 years and never before have I suffered or enjoyed it this intensely, nor with so many dangers,” Valdez said in his CPJ acceptance speech. “The youth will remember this as a time of war. Their DNA is tattooed with bullets and guns and blood, and this is a form of killing tomorrow. We are murderers of our own future.”

He continued: “This is a war, yes, but one for control by the narcos, but we the citizens are providing the deaths, and the governments of Mexico and the United States, the guns. And they, the eminent, invisible and hidden ones, within and outside of the governments, they take the profits.”

Yet despite his international profile, Valdez knew he was not protected. On March 23, after journalist Miroslava Breach was shot in front of her son in the northern border state of Chihuahua, Valdez tweeted: “Let them kill us all, if that is the death penalty for reporting this hell. No to silence.”

[Monica Campbell is a Global Nation Editor/Reporter for Public Radio International’s The World. She previously reported on Latin America and the Caribbean from Mexico City, where she served as the Mexico representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists.]