Are Demographics Really Destiny for the GOP?

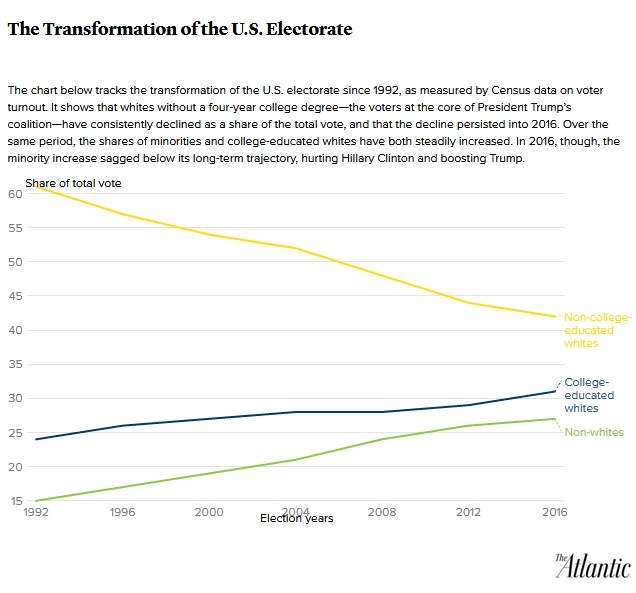

Despite President Trump’s magnetic appeal for working-class whites, those fiercely contested voters continued their long-term decline as a share of the national electorate in 2016, a new analysis of recent Census Bureau data shows.

That continued erosion underscores the gamble Trump is taking by aligning the GOP ever more closely with the hopes and fears of a volatile constituency that, while still large, has been irreversibly shrinking for decades as a share of the total vote. The data analysis on 2016 voting, conducted for The Atlantic by Robert Griffin and Ruy Teixeira of the Center for American Progress’s States of Change project, found that non-college-educated whites declined as a share of the electorate even in the key Midwestern states that tipped the election to Trump.

“This is a good example of just how hard it is to reverse an ongoing trend like this,” said Teixeira, a co-founder of the project, which studies how demographic change affects politics and policy. “It says to Republicans: ‘You have intrinsically placed your bets on a political group that under almost any conceivable circumstances will continue to decline as a share not only of eligible voters, but [of actual] voters going forward.’ If that didn’t in this election, you have to say it’s not going to happen.”

But the new Census numbers on voter participation last year also contain a clear warning signal for Democrats. While the overall U.S. population continues to grow more racially and ethnically diverse, the electorate’s demographic transformation slowed markedly in 2016 because turnout remained surprisingly weak among Hispanics and fell sharply among African Americans without former President Barack Obama on the ballot, according to the findings.

Though minority voters preferred Hillary Clinton by a large margin, those disappointing turnout numbers underscore the difficulty she had mobilizing the Democratic coalition around a message that placed much more emphasis on values and tolerance—so-called “identity politics”—than a bread-and-butter economic message.

“The long-term challenge for Republicans remains unchanged: They still have to figure out how to appeal to the growing proportion of the electorate that is non- white and college-educated,” said GOP pollster Whit Ayres, who worked during the Republican primaries for Trump rival Marco Rubio, the Florida senator. “Trump managed to slip the punch for one election, but that changed nothing about the long-term challenge. For the Democrats … they have to a substantive message that appeals beyond identity politics, and they haven’t figured that out yet.”

Always important, shifts in the electorate’s composition have become even more critical to election outcomes as the distance has widened between the preferences of key groups. Republicans now routinely amass wide margins among whites without a college degree, with exit polls showing Trump establishing the biggest advantage of any GOP nominee since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Democrats consistently dominate among non-white voters. And whites with a college degree usually lean toward Republicans, though much less lopsidedly than their blue-collar counterparts. As both candidate and president, Trump has faced much more resistance among well-educated whites than Republicans usually confront.

There is no single authoritative source on the electorate’s makeup. The two most widely cited are Census data, gleaned from the Current Population Survey, and the Election Day exit polls conducted outside polling places around the country by Edison Research for a consortium of news organizations. Political professionals increasingly rely on detailed studies of state voter files for a third perspective on which Americans voted, although those sources are not as widely available to the public.

The main difference between the two principal public sources is that the exit polls consistently identify whites with at least a four-year college education as a larger share of the vote—and whites without a degree as a considerably smaller share—than the Census does. In a much smaller disparity, the exit polls also regularly find minorities constituting a slightly larger share of the vote than the Census does.

But while starting from different points, the two data sources have largely moved along the same path over the past quarter century. Both the exit polls and Census have found whites without a college degree, the most commonly accepted definition of the white working-class, steadily declining and minorities steadily increasing. The gap between the two data sources on the role of college-educated whites has narrowed considerably since 1992, with the exit polls showing that group largely stable at just over one-third of the electorate and the Census portraying them as steadily rising from a lower starting point to just below one-third. The States of Change analysis of the 2016 Census data shows those trends mostly persisting through last fall’s election, though with changes at the margin that helped tip the final result.

According to that analysis, whites without a college degree cast slightly more than 42 percent of the national vote last year. That was down from more than 44 percent in 2012 and, as Teixeira noted, continued a long-term retrenchment: Census figures have found the share of the vote cast by those Americans has declined in each presidential election since 1992, when it stood at 61 percent.

That slip of just over 2 percentage points between the last two elections, however, represents a smaller decline than average: over 3 percentage points per cycle from 1992 through 2012. (The exit polls also showed the non-college-educated white share of the vote dropping by two points from 2012 to 2016, which was also less severe than its average of just over three points every four years from 1992 through 2012.) The slower rate of decline may measure the power of Trump’s appeal to blue-collar whites. Still, among those voters, turnout edged up only modestly last fall, the Census figures show, with nearly 57.8 percent of eligible voters casting ballots compared with 57 percent in 2012.

By contrast, the States of Change analysis found that the share of the 2016 vote cast by whites holding at least a four-year college degree rose to 31.3 percent, up from 29.4 percent in 2012. That continues a measured but steady increase since 1992, when those well-educated voters represented 24 percent of the electorate, according to Census figures. (Over that same period, the exit polls have found the college-educated white share largely holding steady, growing from 35 percent in 1992 to 36 percent in 2012 and to 37 percent in 2016.) Turnout among these voters improved very slightly from 79 percent in 2012 to 79.1 percent in 2016.

These figures mean that even with Trump’s consistent focus on working-class whites, their turnout in November ran more than 21 percentage points behind that of college-educated whites. That was virtually unchanged from the nearly 22-percentage-point gap four years ago.

A set of state-level Census findings, also analyzed by Griffin and Teixeira, underscores the difficulty of reversing the long-term contraction of the white working-class, even for a candidate as dedicated as Trump to mobilizing them. Though the state data can be volatile, they showed that the share of the vote cast by whites without a college degree declined last year even in each of the five Midwestern states that decided the election: Iowa, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Although the slippage was very small in Wisconsin, in all five states the data showed the share of the vote cast by college-educated whites increased from 2012 to 2016, often by significant amounts.

These results also extend long-term trends: In all five states, Census data have shown non-college-educated whites now constitute a significantly smaller share of the total vote than they did in 1992. Despite this decline, the new results found those whites still represented 50 percent of all voters in Michigan, 51 percent in Pennsylvania, 54 percent in Ohio, nearly 57 percent in Wisconsin, and almost 60 percent in Iowa. In all of those states, exit polls found that Trump amassed significantly wider margins among working-class whites than Mitt Romney did four years earlier. Those gaping margins powered Trump’s narrow victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, the states that keyed his election.

Even so, blue-collar whites’ continued decline in the electorate, including in the states where they are most critical, reaffirms the concerns of Trump’s GOP critics that he is defining the party in a manner that wins over those voters at too high a price: the alienation of white-collar whites and minorities, two groups that are growing in number. “Nothing has repealed the long-term demographic trends in the electorate,” Ayres said. “What Trump did was lock us more completely into a declining portion of the electorate at the cost of an increasing portion of the electorate.”

Moreover, while Trump’s sustained emphasis on nationalist policies on trade and immigration have helped him maintain his connection with blue-collar whites, in both his budget and his support for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, he is backing severe retrenchment of federal programs that benefit large numbers of those voters. As Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center, tweeted last week after the release of Trump’s budget: “Obama-Trump voters get gov’t benefits - and like it.” A Quinnipiac University national poll released Thursday, for instance, found that the House-passed Obamacare replacement faced opposition from not only about two-thirds of both minorities and college-educated whites, but also a plurality of non-college-educated whites.

If the continued decline of blue-collar whites is the principal warning sign for Republicans in the new figures, the red light flashing most brightly at Democrats is the disappointing turnout among minorities. Though Trump presented a uniquely polarizing and provocative foil, the Census figures showed that turnout in 2016 sagged among Hispanics and skidded among African Americans.

Among Hispanics, the States of Change analysis found that turnout declined slightly among those with a college education (down from nearly 71 percent in 2012 to just over 68 percent in 2016) and among those without (from just under 44 percent last time to just under 43 percent this time). Overall, the Census put total Hispanic turnout at just under 48 percent, which is within the narrow range of 47 percent to 50 percent over the past four presidential elections that has frustrated Democrats hoping for larger gains and greater impact.

The most positive sign for Democrats was state-level Census data showing Hispanic turnout surging in Arizona and improving somewhat more modestly in Nevada and Colorado, all states where the party made a significant organizational effort. (Surprisingly, the Census data show Hispanic turnout declining from 2012 in Florida and slipping modestly in Virginia and North Carolina.)

Without Obama on the ballot, turnout among black voters took a harder hit. In 2012, African Americans holding at least a four-year college degree voted at a slightly higher rate than whites with advanced education, and African Americans without degrees turned out at notably higher rates than blue-collar whites. But in 2016, turnout in both categories dropped so sharply that it fell below the levels of college-educated and working-class whites, according to the States of Change analysis. In 2016, turnout sagged to about 73 percent among college-educated African Americans (down from nearly 80 percent in 2012) and to about 56 percent among those without degrees (down from over 63 percent in 2016). Overall, the Census data showed turnout among eligible African Americans dropped fully 7 percentage points from 2012 to 2016, the biggest drop over a single election for the group since at least 1980. In the battlegrounds that tipped the election to Trump, state-level Census data show black turnout plummeting in Wisconsin; skidding in North Carolina, Florida, and Ohio; and declining more modestly in Michigan and Pennsylvania.

Teixeira cautions that further analysis of voting records may produce a less dramatic decline. But he said the shift is unmistakable—and worrisome for Democrats. “I viewed black turnout in a steady, upward trajectory,” he said. “It turns out that the Obama election increases were perhaps more attributable to Obama than we thought.”

Turnout among Asian Americans with and without advanced education improved slightly in 2016, while turnout declined for adults in the “other” and mixed-race category, the Census figures found. These trends blunted the impact of the overall population’s growing diversity. Calculations by William Frey, a Brookings Institution demographer, show the non-white share of the eligible voter population rose to 31 percent in 2016, a two-point gain from 2012. But the minority share of actual voters edged up only slightly, from 26.3 percent in 2012 to 26.7 percent in 2016, according to the Census figures. That’s much lower than the average election-to-election increase in the minority share of eligible and actual voters—about 2 percentage points each in recent elections.

Reflecting their growth in the overall population, Hispanics and Asian Americans combined cast almost exactly 13 percent of all votes in 2016, up from about 11.5 percent in 2012, the Census found. But African Americans declined from about 13 percent of the vote four years ago to 12 percent in November. (The vote share of “other” and mixed race remained essentially unchanged.) Looking at the key Midwestern states, the black share of the vote slightly increased in Iowa and Michigan from 2012 to 2016, but declined in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and, especially, Wisconsin.

While placing the national minority vote share at 29 percent, slightly higher than the Census did, the exit polls also showed a smaller-than-average increase from 2012 to 2016, with a decline in the African American share offsetting small gains among Hispanics and Asians.

From across party lines, both Teixeira and Ayres see a common thread between Clinton’s big deficit among working-class whites and the disappointing turnout results among minorities. Each believes that both problems reflected Clinton’s inability to connect with both groups of voters on their core economic concerns while her campaign stressed other issues—particularly her support for an inclusive society and the case against Trump.

“What was the message that the median voter might have taken away?” Teixeira asked. “You shouldn’t vote for Donald Trump because he’s a bad man, and Hillary Clinton is a nice person and we’re ‘stronger together.’ That was a really uncompelling message, not only for white, non-college voters but for blacks and Latinos as well. These kinds of voters are looking for other changes in their lives.”

Assistant editor Leah Askarinam contributed.