It’s Time to Bust The Myth: Most Trump Voters Were Not Working Class

The Atlantic said that “the billionaire developer is building a blue-collar foundation.” The Associated Press wondered what “Trump’s success in attracting white, working-class voters” would mean for his general election strategy. On Nov. 9, the New York Times front-page article about Trump’s victory characterized it as “a decisive demonstration of power by a largely overlooked coalition of mostly blue-collar white and working-class voters.”

During the primaries, Trump supporters were mostly affluent people.

The misrepresentation of Trump’s working-class support began in the primaries. In a widely read March 2016 piece, the writer Thomas Frank, for instance, argued at length that “working-class white people … make up the bulk of Trump’s fan base.” Many journalists found colorful examples of working-class Trump supporters at early campaign rallies. But were those anecdotes an accurate representation of the emerging Trump coalition?

There were good reasons to be skeptical. For one, most 2016 polls didn’t include information about how the people surveyed earned a living, that is, their occupations — the preferred measure of social class among scholars. When journalists wrote that Trump was appealing to working-class voters, they didn’t really know whether Trump voters were construction workers or CEOs.

Moreover, according to what is arguably the next-best measure of class, household income, Trump supporters didn’t look overwhelmingly “working class” during the primaries. To the contrary, many polls showed that Trump supporters were mostly affluent Republicans. For example, a March 2016 NBC survey that we analyzed showed that only a third of Trump supporters had household incomes at or below the national median of about $50,000. Another third made $50,000 to $100,000, and another third made $100,000 or more and that was true even when we limited the analysis to only non-Hispanic whites. If being working class means being in the bottom half of the income distribution, the vast majority of Trump supporters during the primaries were not working class.

But what about education? Many pundits noticed early on that Trump’s supporters were mostly people without college degrees. There were two problems with this line of reasoning, however. First, not having a college degree isn’t a guarantee that someone belongs in the working class (think Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg). And, second, although more than 70 percent of Trump supporters didn’t have college degrees, when we looked at the NBC polling data, we noticed something the pundits left out: during the primaries, about 70 percent of all Republicans didn’t have college degrees, close to the national average (71 percent according to the 2013 Census). Far from being a magnet for the less educated, Trump seemed to have about as many people without college degrees in his camp as we would expect any successful Republican candidate to have.

Trump voters weren’t majority working class in the general election, either.

What about the general election? A few weeks ago, the American National Election Study — the longest-running election survey in the United States — released its 2016 survey data. And it showed that in November 2016, the Trump coalition looked a lot like it did during the primaries.

Among people who said they voted for Trump in the general election, 35 percent had household incomes under $50,000 per year (the figure was also 35 percent among non-Hispanic whites), almost exactly the percentage in NBC’s March 2016 survey. Trump’s voters weren’t overwhelmingly poor. In the general election, like the primary, about two thirds of Trump supporters came from the better-off half of the economy.

But, again, what about education? Many analysts have argued that the partisan divide between more and less educated people is bigger than ever. During the general election, 69 percent of Trump voters in the election study didn’t have college degrees. Isn’t that evidence that the working class made up most of Trump’s base?

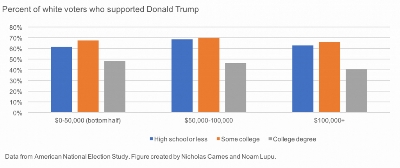

The truth is more complicated: many of the voters without college educations who supported Trump were relatively affluent. The graph below breaks down white non-Hispanic voters by income and education. Among people making under the median household income of $50,000, there was a 15 to 20 percentage-point difference in Trump support between those with a college degree and those without. But the same gap was present — and actually larger — among Americans making more than $50,000 and $100,000 annually.

To look at it another way, among white people without college degrees who voted for Trump, nearly 60 percent were in the top half of the income distribution. In fact, one in five white Trump voters without a college degree had a household income over $100,000.

Observers have often used the education gap to conjure images of poor people flocking to Trump, but the truth is, many of the people without college degrees who voted for Trump were from middle- and high-income households. That’s the basic problem with using education to measure the working class.

In short, the narrative that attributes Trump’s victory to a “coalition of mostly blue-collar white and working-class voters” just doesn’t square with the 2016 election data. According to the election study, white non-Hispanic voters without college degrees making below the median household income made up only 25 percent of Trump voters. That’s a far cry from the working-class-fueled victory many journalists have imagined.

Forget the narrative

A recent National Review article about Trump’s alleged support among the working class bordered on a call to arms against the less fortunate, saying that, “The white American underclass is in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles. Donald Trump’s speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin” and that “the truth about these dysfunctional downscale communities is that they deserve to die.”

This kind of stereotyping and scapegoating is a dismaying consequence of the narrative that working-class Americans swept Trump into the White House. It’s time to let go of that narrative.

What deserves to die isn’t America’s working-class communities. It’s the myth that they’re the reason Trump was elected.

[Nicholas Carnes is an assistant professor of public policy at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. He is the author of White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Noam Lupu is an associate professor of political science at Vanderbilt University. He is the author of Party Brands in Crisis: Partisanship, Brand Dilution, and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America (Cambridge University Press, 2016).]