Capital, Crisis, and Corbyn

The UK election result is a personal disaster for the Conservative leader, Theresa May. She called the snap election to get a big majority and crush the opposition Labour Party and its left-wing leadership. But instead the Conservatives lost seats and its majority in parliament, and Labour under leftist Jeremy Corbyn increased its share of the vote dramatically after a vigorous campaign.

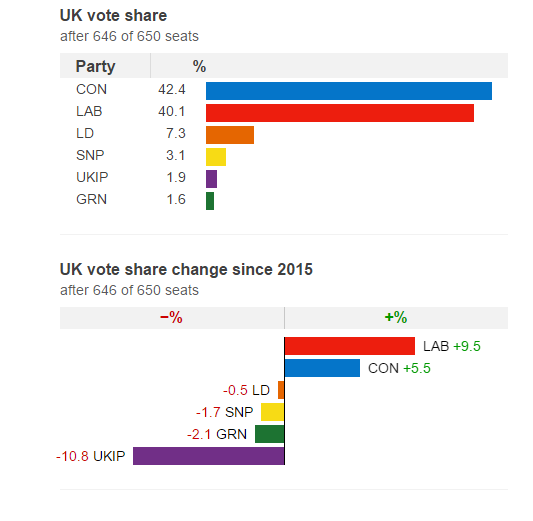

The turnout was 69%, the highest since 1997, when the figure was 71.4%. It seems that young people turned out for Labour, particularly in the big cities. Labour gained 10% to reach 40%, while the Conservatives also increased their share by 5% to 42%. The big loser was the anti–European Union, anti-immigration party UKIP, which collapsed.

There is now what is called a “hung parliament,” with no overall majority for one party. This makes the upcoming Brexit talks with the EU a mess, as there is no “strong and stable” government to negotiate.

But more than a disaster for May and the Conservatives, this is one for the British ruling class. The negotiations over the terms of Britain leaving the EU are supposed to start on June 19, and now the EU negotiators will face British ones having lost their majority in the British Parliament. The terms of any deal are going to be hard on the interests of British capital: on the terms of trade, employment mobility, and on capital flows for the City of London.

At the same time, the UK economy is already struggling. In the first quarter of 2017, the UK’s real GDP grew more slowly than any other top (G7) economy. The British pound dropped sharply after the election result, and it is likely to fall further as foreign investors consider their options, given the uncertainty of what will happen with Brexit and the paralyzed position of a minority Conservative government unable to carry out any economic policy measures. Sterling has already fallen by over 15% since the Brexit referendum result last year.

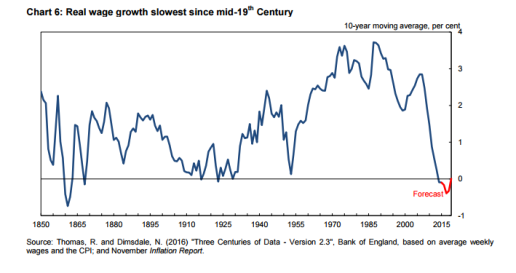

That has led to a substantial rise in prices in the shops from higher import prices. Inflation is likely to rise further, driving down real incomes for the average British household.

And that is after British households have suffered the longest stagnation in real incomes in the last 166 years!

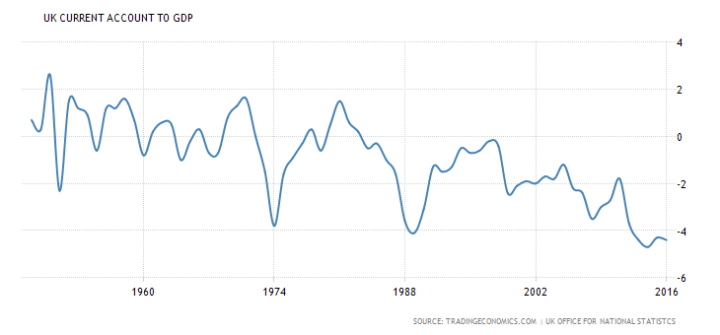

The UK trade deficit with the rest of the world keeps widening as British exporters fail to take advantage of a weaker pound and import prices rise.

The reason that British capital is not gaining from the devaluation of the currency is that British manufacturing and services are still not competitive because productivity growth is virtually zero.

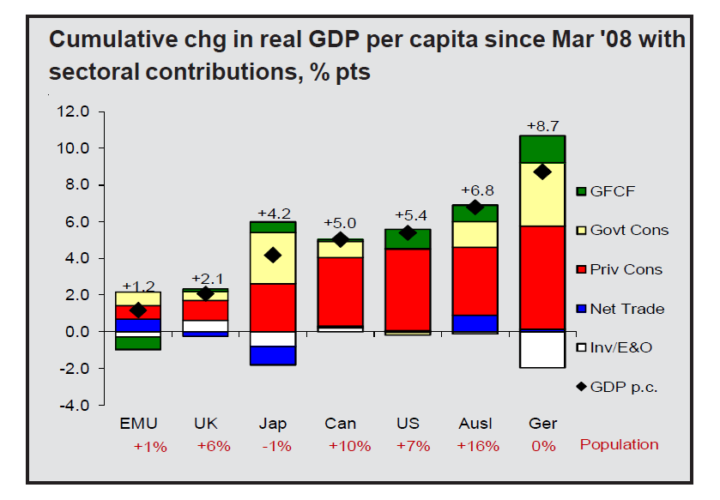

It’s been nine years since the start of the global financial crash in 2008. Since then, real GDP per person in the major economies has risen on average at less than 1% a year. That’s well below the trend average before the global crash. Germany has done best with a cumulative rise of 8.7%, even better than the lucky country, Australia (6.8%). But the UK has managed just 2% over nine years!

The main reason is the sharp fallback in the growth of labor productivity. The UK economy has depended instead for its (limited) growth since the end of the Great Recession on a consumer boom and a big increase in immigration of young people from Eastern Europe and the EU.

According to the most recent ONS statistics, there has been no increase in the number of UK-born in employment over the last year. All the net increase in employment has been due to those born abroad. If the Brexit negotiations go ahead and the free movement of labor is lost, British business is going to have to use domestic labor and skills. Employment growth will slow, and national output will falter unless productivity rises.

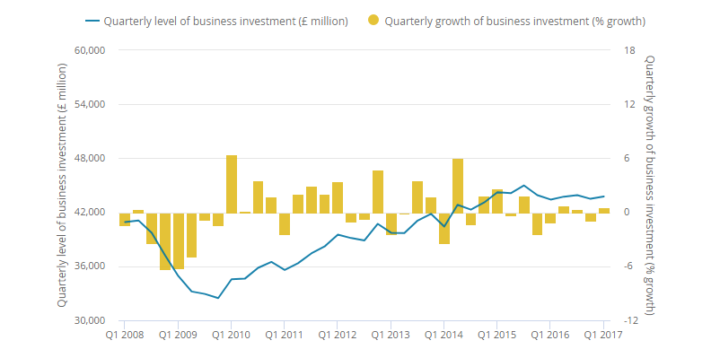

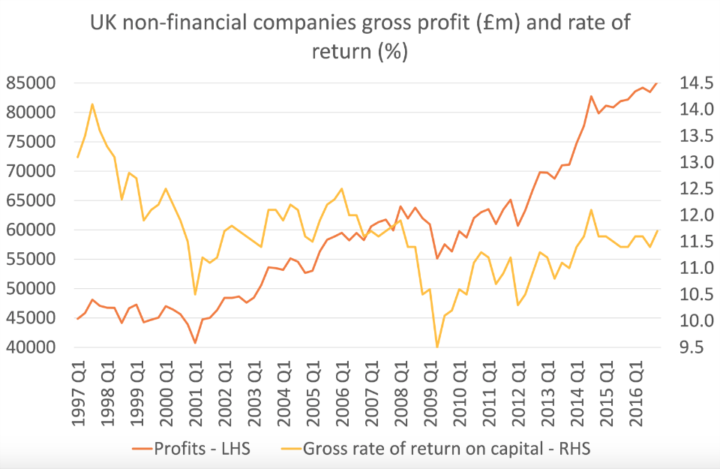

And the main reason it won’t is the failure of British businesses to invest in productive capital, i.e. new machinery, plants, and computer software. Business investment has hardly risen since the Great Recession, even as profitability recovered.

That’s because profits were concentrated in the large companies while the small- and medium-sized companies made little and could not get credit. The large companies (mainly tech and finance) returned their profits to shareholders in dividends and share buybacks or held cash abroad in tax havens, rather than invest. And business profitability in the UK started to fall back even before the Brexit vote.

The UK economy is set to enter a period of stagnation at best. The OECD’s economists are already forecasting that the UK economy will slow down to just 1% next year as Brexit bites. And there is every likelihood of a new global recession in the next year or two.

After the 2015 election, which the Conservatives won narrowly, I argued that the victory was a poisoned chalice and the Tories would not win the next election. I said that because of the likely global recession before 2020. But Brexit cut across all that for a while.

This result was partly a follow-up from Brexit as the Conservatives did better in the areas that voted to leave the EU and Labour did better in those that voted to stay in. But now the election also brought back the issue of living standards of the many against the wealth of the few. That led to May’s failure.

This minority Conservative government is going to find it difficult to survive for long. There could well be a new general election before the year is out, and that could well lead to a Labour government aiming to reverse the neoliberal policies of the last thirty years. But if the UK capitalist economy is in dire straits, a Labour government would face an immediate challenge to the implementation of its policies.

_______________________________________

Michael Roberts has worked as an economist in the City of London for over thirty years. He is the author of The Great Recession: a Marxist view and most recently, The Long Depression.

The spring issue of Jacobin, “By Taking Power,” is out now. To celebrate its release, subscriptions start at just $14 by following this link.