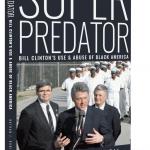

Bill Clinton: His Career a Disaster for Black Americans

Bristling at the protesters’ continual outbursts, Clinton began to raise his voice.

He challenged the activists’ portrayals of his record on welfare and crime. He insisted that thanks to his policies, poverty had decreased and our streets were safer. Clinton claimed that the protesters simply didn’t want to know the facts, as evidenced by the vehemence of their clamor: “They won’t hush. When someone won’t hush and listen, that ain’t democracy. They’re afraid of the truth. Don’t be afraid of the truth.”

Of course, one could perhaps take issue with Clinton’s equation of hushing and democracy (“Hush and Listen” sounding like the official slogan of a folksy police state run by bayou Stalinists). But the testiest part of the exchange, and the one that made the next morning’s headlines, concerned the phrase “superpredator.”

The seeds of the “superpredator” scuffle were sown many years earlier. At an event in New Hampshire in 1996, Hillary Clinton had been discussing the administration’s “organized effort against gangs.” She described gangs as a nationwide problem, one requiring a muscly policy response, with our generation having to face up to gangs “just as in a previous generation we had an organized effort against the mob.”

Gangs were a scourge, she suggested, and to deal with them we must exercise the full might of the law’s brawny arm. “We need to take these people on,” she declared.

But it was a particular couple of sentences in Hillary Clinton’s gang monologue that would haunt her, and would be the direct cause of Bill Clinton’s news-making outburst twenty years later. Describing the type of juvenile gang members she was referring to, Hillary said:

They are not just gangs of kids anymore. They are often the kinds of kids that are called “super-predators.” No conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way but first we have to bring them to heel.

Her words were not controversial at the time. But in the 2016 election, they proved a source of significant embarrassment.

By that time, the “tough on crime” political rhetoric of the 1990s was under strong criticism. The Black Lives Matter movement arose as a reaction to decades of abusive policing practices and failed criminal justice policies. To a new generation of activists, Hillary’s having called kids “superpredators” seemed perverse.

At first, Clinton seemed bewildered by the criticism. When a Black Lives Matter activist named Ashley Williams crashed a Clinton fundraiser holding a sign with the infamous quote, a tense exchange ensued:

Hillary Clinton: I think we’ve got somebody saying here, have you? [reading sign] “Bring them to heel?”

Ashley Williams: We want you to apologize for mass incarceration. I’m not a superpredator, Hillary Clinton.

Clinton: Okay fine, we’ll talk about it.

Williams: Will you apologize to black people for mass incarceration?

Clinton: Well, can I talk, and then maybe you can listen to what I say. Fine. Thank you very much. There are a lot of issues in this campaign. The very first speech that I gave back in April was about criminal justice reform.

Williams: You called black people “superpredators.”

Unidentified Fundraiser Attendee: You’re being inappropriate, that’s rude.

Williams: She called black people “superpredators,” that is rude.

Clinton: Do you want to hear the facts or do you just want to talk?

Williams: I know that you called black people “superpredators” in 1994, please explain it to us. You owe black people an apology.

Clinton: If you give me a chance to talk, I’ll come to your side . . . You know what! Nobody’s ever asked me before. You’re the first person to ask me and I am happy to address it. But you are the first person to ask me.

At that point, Clinton moved on, and Williams was escorted from the event by Secret Service. But faced with the prospect of continuing to be dogged by sign-wielding Black Lives Matter supporters, Clinton soon repudiated her use of the phrase in a conversation with the Washington Post’s Jonathan Capehart.

“Looking back,” she said, “I shouldn’t have used those words, and I wouldn’t use them today.” She emphasized her commitment to children, and mentioned the importance of ending the notorious “school-to-prison pipeline” that ensnares so many young African Americans.

Given that Hillary herself had just disowned the words and apologized for using them, one might therefore have expected Bill Clinton to display a similar contrition when confronted by the activists in Philadelphia. But when they mentioned the phrase “superpredator,” he exploded in unqualified defense of the term:

I don’t know how you would describe the gang leaders who got thirteen-year-olds hopped up on crack and sent them out in the streets to murder other African-American children! Maybe you thought they were good citizens, didn’t. You are defending the people who kill the lives you say matter.

Clinton went on to defend every aspect of his criminal justice policy, chiding the activists by suggesting that they didn’t care about victims. This was despite his having previously apologized to the NAACP for his role in expanding the prison system, saying “I signed a bill that made the problem worse . . . and I want to admit it.”

Bill Clinton’s words were certainly curious. A man who has always portrayed himself as a friend to black Americans, Clinton had seemed just as sincere in his apology for his actions as in his later defense of them.

Which was the real Clinton: the one who apologized for his crime bill, or the one who snapped at people who criticized his crime bill? Was Clinton a good-hearted and progressive-minded criminal justice reformer, or an insensitive relic of the “tough on crime” era who still believed in conservative fables about roving sociopathic African American preteens? To many observers, the whole thing seemed paradoxical.

But for those acquainted with Clinton’s political history, there was nothing especially “baffling” about his behavior in Philadelphia.

Rather, it was simply the most blatant expression of traits that have been present in Clinton’s character since his early political career. From the very beginning, Clinton’s political success has been built on his skillful maneuvering between different rhetorical stances, his “triangulation” between right and left.

Bill Clinton has always been a person who says one thing to the NAACP, and another to white audiences. What happened in Philadelphia may have startled the young black activists who sought to challenge Clinton, but it shouldn’t have. For twenty years, Bill Clinton has shown a tendency to reverse himself on prior commitments, most especially those made to African American constituencies.

Perhaps the only surprising thing about this is that anybody is still surprised.

A Threat to Civilization

The myth of the “superpredator” would have terrible consequences for American children. In the mid 1990s, fueled by alarmist pseudo-scholarship by quack criminologists, a number of politicians sounded the alarm about a concerning new trend: the rise of a new breed of sociopathic juvenile delinquent, incapable of empathy and hellbent on robbing, raping, and terrorizing every decent churchgoing middle American community.

The 1980s and 1990s were a heyday for nationwide moral panics. The coming of the superpredators was just one of the paralyzing terrors of the period, which also included widespread fear of Satanic abuse at daycares and razorblades in Halloween candy. The superpredator legend, however, was more deeply insidious.

The term was coined by John DiIulio Jr, a professor at Princeton University. DiIulio interpreted rising juvenile crime statistics to mean that a “new breed” of juvenile offender had been born, one who was “stone cold,” “fatherless, Godless, and jobless,” and had “absolutely no respect for human life and no sense of the future.”

DiIulio and his coauthors elaborated that superpredators were:

Radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters, including ever more preteenage boys, who murder, assault, rape, rob, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, join gun-toting gangs, and create serious communal disorders. They do not fear the stigma of arrest, the pains of imprisonment, or the pangs of conscience. They perceive hardly any relationship between doing right (or wrong) now and being rewarded (or punished) for it later. To these mean-street youngsters, the words “right” and “wrong” have no fixed moral meaning.

For devising this theory, DiIulio was rewarded with an invitation to the White House, where he and a group of other experts spent three and a half hours with President Clinton.

Confirming DiIulio’s analysis was James Q. Wilson, the conservative political scientist who had devised the theory of “broken windows” policing. The broken windows theory posited that minor crimes in a neighborhood (such as the breaking of windows) tended to lead to major ones, so police should harshly focus on rounding up petty criminals if they wanted to prevent major violent crimes.

Put into practice, this amounted to the endless apprehension of fare-jumpers and homeless squeegee people. It also created the intellectual justification for totalitarian “stop and frisk” policies that introduced an exasperating and often terrifying ordeal into nearly every young black New Yorker’s life.

“Broken windows” had very little academic support (it hadn’t been introduced in a peer-reviewed journal, but in a short article for the Atlantic), but Wilson still felt confident in pronouncing on the “superpredator” phenomenon. He predicted that by the year 2000, “there will be a million more people between the ages of fourteen and seventeen than there are now” and “six percent of them will become high rate, repeat offenders — thirty thousand more young muggers, killers and thieves than we have now.”

DiIulio and Wilson said that it was past time to panic. “Get ready,” warned Wilson. Not only were the superpredators here, but a lethal tsunami of them was rising in the distance, preparing to engulf civilization.

As James C. Howell documents, just a year later, as crime rates continued to decrease, DiIulio “pushed the horizon back ten years and raised the ante.” This time DiIulio projected that “by the year 2010, there will be approximately 270,000 more juvenile super-predators on the streets than there were in 1990.” Like a Baptist apocalypse forecaster, the moment the sky didn’t fall according to prophecy, a new doomsday was announced, with just as much confidence as the last.

So despite all evidence to the contrary, segments of the Right continued to anticipate “a bloodbath of teenager-perpetrated violence,” perpetrated by “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless” “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” and “have absolutely no respect for human life.”

The notion gained political cache, and was spoken of in Congress and on the national media. It was even propagated, and given a major credibility boost, by one or two prominent liberals, perhaps the most prominent of whom was Hillary Rodham Clinton.

There was always a race element to the superpredator theory, which is why The New Jim Crow author and legal scholar Michelle Alexander says Clinton “used racially coded rhetoric to cast black children as animals.”

It wasn’t just subtext; DiIulio spoke in explicitly racial terms. “By simple math,” he wrote, “in a decade today’s 4-to-7-year-olds will become 14-to-17-year-olds. By 2005, the number of males in this age group will have risen about 25 percent overall and 50 percent for blacks. [emphasis added] To some extent, it’s just that simple: More boys begets more bad boys . . . [The additional boys will mean] more murderers, rapists and muggers on the streets than we have today.”

DiIulio speculated that “the demographic bulge of the next 10 years will unleash an army of young male predatory street criminals who will make even the leaders of the Bloods and Crips — known as OGs, for ‘original gangsters’ — look tame by comparison . . . ” DiIulio explained that these boys traveled in “wolf packs,” and that black violence “tended to be more serious” than white violence, “for example, aggravated assaults rather than simple assaults, and attacks involving guns rather than weaponless violence.”

Michelle Alexander may therefore overstate the extent to which the superpredator language was “coded” in the first place; the theory’s most prominent advocate was openly stating that the “wolves” in question were black. He could only have been more explicit about his meaning if he had simply written the “n-word” over and over on the op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal.

In the years since, nearly everyone has abandoned the superpredator story, for the essential reason that it was, to put it simply, statistically illiterate race-baiting pseudoscience. As a group of criminologists explained in a brief to the Supreme Court, “the fear of an impending generation of superpredators proved to be unfounded. Empirical research that has analyzed the increase in violent crime during the early- to mid-1990s and its subsequent decline demonstrates that the juvenile superpredator was a myth and the predictions of future youth violence were baseless.”

In fact, the criminologists had “been unable to identify any scholarly research published in the last decade that provides support for the notion of the juvenile superpredator.” Among the criminologists who filed the brief were John DiIulio and James Q. Wilson, who humbly conceded that their findings had been in error.

The harm done to young people, however, was incalculable.

Having been scientifically diagnosed as remorseless and demonic, poor children accused of crimes were increasingly given the kind of harsh punishments previously reserved for adults. New York University criminologist Mark Kleiman says there was a direct link between that single “fallacious bit of science” and the expansion of the use of the adult justice system to prosecute children.

“Based on [the superpredator theory],” Kleiman writes, “dozens of states passed laws allowing juveniles to be tried and sentenced as adults, with predictably disastrous results.” As the Equal Justice Initiative has observed, “the superpredator myth contributed to the dismantling of transfer restrictions, the lowering of the minimum age for adult prosecution of children, and it threw thousands of children into an ill-suited and excessive punishment regime.”

In early 1996, the Sunday Mail described the panic that was overtaking Illinois:

“It’s Lord of the Flies on a massive scale,” Chicago’s Cook County State Attorney Jack O’Malley said . . . We’ve become a nation being terrorized by our children . . . ” Already, the State of Illinois has introduced new laws to deal with this terrifying new “crime bomb,” ruling that children as young as 10 will be sent to juvenile jails. The State is rushing construction of its first “kiddie prison” to replace the traditional, less punitive “youth detention facility” to enforce the get-tough policy of jail cells instead of cozy dormitories.

The shift to viewing kids as comparable to the worst adult offenders allowed all manner of abuses to be inflicted on young people for whom the effects are especially damaging. Juvenile solitary confinement has been routinely used in American prisons, despite having been recognized as a form of torture by United Nations Human Rights Committee. Kids have been held in tiny cells for twenty-three hours per day, leading to madness and suicide.

The practice produces stories such as that of Kalief Browder, who was sent to Rikers Island jail at the age of sixteen, spending two years in solitary confinement awaiting trial for stealing a backpack, and ultimately killing himself after finally being released and having the charges dropped. A joint report by the ACLU and Human Rights Watch, which interviewed over one hundred people who had been held in solitary confinement while under the age of eighteen, summarized some of the intense psychological torment inflicted:

Many of the young people interviewed spoke in harrowing detail about struggling with one or more of a range of serious mental health problems during their time in solitary. They talked about thoughts of suicide and self-harm; visual and auditory hallucinations; feelings of depression; acute anxiety; shifting sleep patterns; nightmares and traumatic memories; and uncontrollable anger or rage. Some young people, particularly those who reported having been identified as having a mental disability before entering solitary confinement, struggled more than others. Fifteen young people described cutting or harming themselves or thinking about or attempting suicide one or more times while in solitary confinement.

Housing juveniles in adult facilities can be an equally inhumane practice in itself. As the weakest members of the population, juveniles housed in adult facilities are likely to be brutally raped by older inmates, and are at an increased risk of suicide.

T. J. Parsell was sent to prison in Michigan at the age of seventeen for robbing fifty-three dollars from a one-hour photo store using a toy gun. He describes his arrival:

On my first day there — the same day that my classmates were getting ready for the prom — a group of older inmates spiked my drink, lured me down to a cell and raped me. And that was just the beginning. Laughing, they bragged about their conquest and flipped a coin to see which one of them got to keep me. For the remainder of my nearly five-year sentence, I was the property of another inmate.

Teenagers like Parsell were being housed in adult facilities long before the “superpredator” horror stories. But the more young offenders are dehumanized, the more dilapidated becomes the thin barrier of empathy that keeps society from inflicting psychological, physical, and emotional torment on the weak. As Natasha Vargas-Cooper writes, while “the scourge of the super-predators never came to be … the infrastructure for cruelty, torture, and life-long captivity of juvenile offenders was cemented.”

But to say the “superpredator” notion has been “discredited” is to overestimate the extent to which it was accepted in the first place, and risks exonerating those who recited the term during the mid nineties. The moment the “superpredator” concept was introduced, reputable criminologists stepped forward to rebut it. Few serious scholars gave the notion any credence, and they made their objections loudly known.

“Everybody believes that just because it sounds good,” the research director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice told the press in 1996. Harvard government professor David Kennedy said that “What this whole super-predator argument misses is that [increasing teen violence] is not some inexorable natural progression” but rather the product of “very specific” social dynamics such as the easy availability of guns.

Other public policy experts called the idea “unduly alarmist” and said its proponents “lack a sense of history and comparative criminology.” DiIulio himself didn’t try to persuade the rest of his field; the Toronto Star reported that “asked recently to cite research supporting his theory, DiIulio declined to be interviewed.”

The political conservatism of the theory was hardly smuggled in under cover of night. DiIulio’s “Coming of the Super Predators” first appeared in William Kristol’sconservative Weekly Standard, and the handful of scholars who peddled the theory had strong, open ties to right-wing politics, so it was plainly partisan rather than scholastic.

Even the language used by the professors, of “Godless” and “brutal” juveniles without “fixed values,” was plainly the talk of Republican Party moralists, rather than dispassionate social scientists. Nobody in the professional circles of a “children’s rights” liberal like Hillary Clinton would have given the “superpredator” concept a lick of intellectual credence, even when it was at the peak of its infamy.

It was therefore deeply wrong to spread the lie even when it was most popular. Yet to defend it in 2016, as Bill Clinton did, is on another level entirely.

When Bill Clinton said in Philadelphia that he didn’t know how else one would describe the kids who got “thirteen-year-olds hopped up on crack and sent them out to murder” other kids, he revived an ugly legend that led to the incarceration and rape of scores of young people.

Speaking this way can still have harmful ripple effects. When Washington Post writer Jonathan Capehart reported Hillary Clinton’s apology for her remark, he implied that superpredators did exist, but that they didn’t include upstanding young people like the Black Lives Matter activist who had challenged Clinton. Folk tales are slow to die, and people’s fear of teen superpredators is easily revived.

It took years to debunk this tale the first time around; once people believe that young people are potential superpredators, they become willing to impose truly barbaric punishments on kids who break the law.

After all, if such offenders are not actually children, but superpredators, one need not empathize with them. One can talk in terms like “bring them to heel,” which is the sort of thing one says about a dog.

It may have been surprising, given that Hillary Clinton has made a strong effort to connect with African-American voters, that Bill Clinton would have revived a nasty racist cliché about animalistic juveniles. But in fact, this simultaneous maintenance of warmth toward individual African Americans and support for policies that hurt the African American community has been a consistent inconsistency throughout Bill Clinton’s political career.

Not a Bug, a Feature

Bill Clinton has long been famous for his unusually congenial relationship with black people. Part of this likely comes from African Americans’ respect for Clinton’s rise from a humble Southern upbringing; Jesse Jackson Jr said that “African Americans identify with Bill Clinton’s personal story and personal experience.”

But many who met Clinton were also impressed by how comfortable and natural he seemed when interacting with black people. Unlike most white politicians, who even when well-intentioned become clumsy and guilt-ridden in conversations with people of other races, Bill Clinton seemed to legitimately enjoy spending time around African Americans.

“He would throw his arm around a black person and shoot the breeze,” recounts former Congressional Black Caucus leader Kweisi Mfume. “He had a way of connecting with black folks that most presidents simply didn’t have.”

Clinton golfed regularly with his black adviser and best friend Vernon Jordan, and seemed to love attending black church services and schmoozing with parishioners; for the president to actually have preexisting close personal relationships with black people was unprecedented. “He understands the black experience,” says Harvard Law School professor Charles Ogletree.

But Clinton’s personal warmth toward African Americans did not translate into policies that favored the majority of African Americans’ interests.

Throughout his presidency, Clinton’s actual actions on issues relevant to black Americans were at odds with his repeated rhetorical commitments to civil rights and racial equality. Clinton presided over a massive continuing expansion of the American prison system, escalated the War on Drugs, and made it easier to administer the death penalty while opposing an effort by black legislators to prohibit racially biased capital punishment.

In social policy, Clinton campaigned on a plan to end the welfare system, and successfully did so, promoting, passing, and signing an act that all but eliminated government financial support for poor families. And Clinton’s deregulation of the financial system laid the foundation for the disastrous economic crisis that would wipe out black wealth a few years after he left office.

In fact, when Bill Clinton’s actions, rather than his words, are scrutinized closely, they reveal a record far more damaging to black interests than that of even many Republican presidents.

George W. Bush, for all his atrocities abroad, never signed any law that inflicted the kind of harm that Clinton’s crime and welfare policies did. As Michelle Alexander has observed, Clinton escalated the “war on drugs” “beyond what many conservatives had imagined possible … ultimately doing more harm to black communities than Reagan ever did.”

Historian Christopher Brian Booker refers to Clinton’s “central role in the incarceration binge in the black community,” and Charles Ogletree has called it “shocking and regrettable that more African Americans were incarcerated on Bill Clinton’s watch than any other president’s in the history of the United States.”

Yet despite the record of his presidency, Clinton always has managed to maintain a sense of goodwill among a large majority of African Americans. In 2002, he was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame alongside Al Green, becoming the first white inductee in the Hall of Fame’s ten-year existence. Clinton’s African-American former transportation secretary Rodney Slater has called him a “soul brother” who “wanted our love and wanted to share his love with us.”

And though the quote’s original context became mangled over time, Toni Morrison’s remark about Clinton as the “first black president” has stuck as a label for Clinton, with plenty of blacks acknowledging that, even if Clinton wasn’t the first black president, he was certainly the first president that black people truly liked.

He therefore escaped serious blowback among African Americans, even as the prisons became engorged with young black men and young black mothers were cast into low-paying jobs by Clinton’s Dickensian “workfare” initiative. Because Clinton gave the appearance of caring, which no other president before him had done, he was cut a stunning amount of slack.

As African-American Arkansas newspaper columnist Deborah Mathis explained, “they made allowances for Bill Clinton because they thought that his heart was good and it didn’t matter that some of his policies were lacking.” Clinton would always be sure to meet with and listen to black leaders before inevitably double-crossing them.

The respect Clinton showed toward black advisers and congressmen (he never missed the annual dinner of the Congressional Black Caucus) went a long way to help him earn their forgiveness for his actual substantive decisions.

Black Entertainment Television CEO Robert Johnson explained that by “iving props to black folks for coming out and voting, going to churches saying ‘you’re the reason I’m here and I will always be there for you,’ the guy could get away with anything.” Indeed, Clinton got away with nearly everything, earning very little flak from black voters even as he betrayed nearly every one of their policy priorities.

To suggest that this means black voters were somehow “fooled” by Clinton would be both demeaning and untrue. Certainly, it seems paradoxical that Clinton could remain beloved by a constituency on whom his policies inflicted terrible harm, and whose ideals he shamelessly betrayed over and over.

But the explanation offered by Clinton’s African-American supporters, that it was simply nice to actually be listened to for once, is perfectly understandable. Clinton spoke to black voters like they mattered, and in a way that didn’t seem patronizing or forced, and in doing so instantly differentiated himself from every single other white politician in the country.

But one doesn’t have to imply that Clinton hoodwinked black voters in order to point out that this achievement, in itself, is not really an achievement at all. “Treating black America like they exist” may have won Clinton first prize among white people, but it really shouldn’t win anybody a prize at all. In reality, not treating black America like they exist is an outrage, and what Clinton did should be the basic precondition of being a moral human being.

It in no way delegitimizes the feelings of African Americans to argue that they had the right to expect more. Mere acknowledgment may be nice, but to put someone into the Black Hall of Fame because he was a non-patronizing Southerner sets a very low standard indeed.

[Author Nathan J. Robinson is the editor of Current Affairs magazine. A graduate of Yale Law School and a doctoral candidate at Harvard in social policy and sociology, he has written for The Washington Post, The Nation, Al Jazeera and The New Republic.]