A Case for Reparations at the University of Chicago

Julia Leakes yearned to be reunited with her family. In 1853, her two sisters showed up for sale along with her thirteen nieces and nephews in Lawrence County, Mississippi. Julia used all the political capital an enslaved woman could muster to negotiate the sale of her loved ones to her owner, Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas’s semi-literate white plantation manager told him “our negros begs for you to by them.” Despite assurances that this would “be a good arrangement,” Douglas refused to shuffle any of his 140+ slaves to reunite this separated slave family. Instead, Julia’s siblings, nieces, and nephews were put on the auction block where they vanished from the historical record.1

Unfortunately, things went from bad to worse for Julia. By 1859, she had a 1 in 3 chance of being worked to death under Douglas’s new overseer in Washington County, Mississippi. Douglas’s mistreatment of his slaves became notorious. According to one report, slaves on the Douglas plantation were kept “not half fed and clothed.”2 In another, Dr. Dan Brainard from Rush Medical College stated that Douglas’s slaves were subjected to “inhuman and disgraceful treatment” deemed so abhorrent that even other slaveholders in Mississippi branded Douglas “a disgrace to all slave-holders and the system that they support.”3

The University of Chicago does not exist apart from Julia Leakes and the suffering of her family—it exists because of them. Between 1848 and 1857, the labor and capital that Douglas extracted from his slaves catapulted his political career and his personal fortune. Slavery soon provided him with the financial security and economic power to donate ten acres of land (valued at over $1.2 million in today’s dollars) to start the University of Chicago in 1857. This founding endowment, drenched in the blood of enslaved African Americans, was leveraged by the University of Chicago to borrow more than $6 million dollars in today’s terms to build its Gothic campus, its institutional structures, its organizational framework, its vast donor network, and an additional $4 million endowment before 1881. In short, the University of Chicago owes it entire presence to its past with slavery.

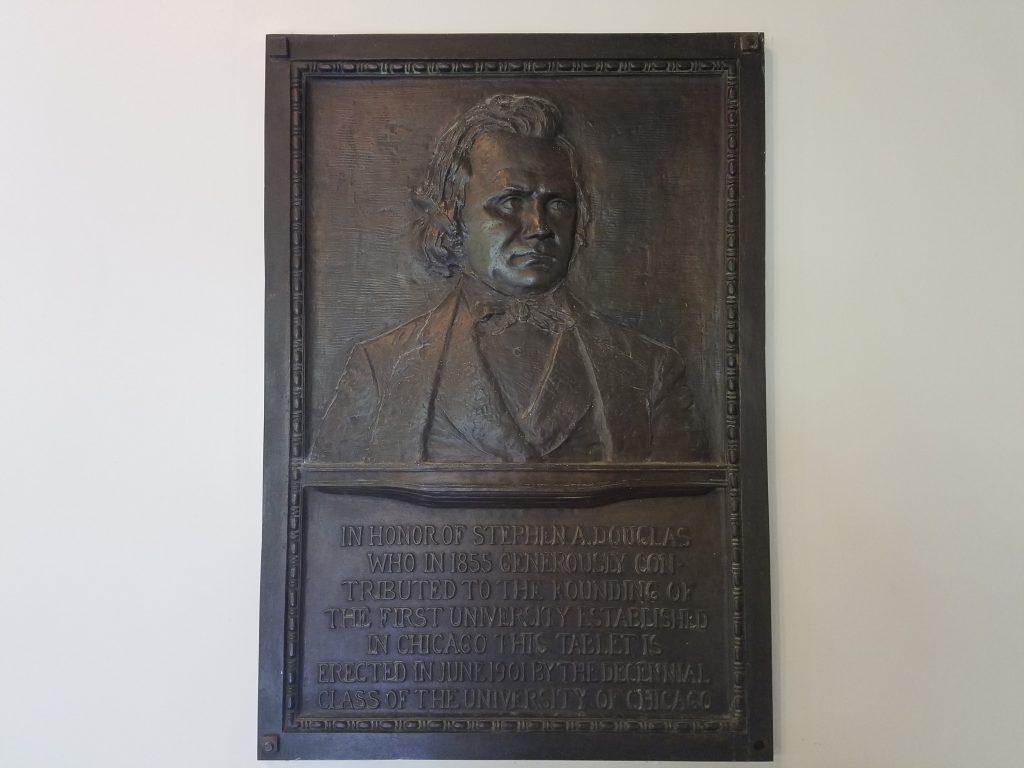

When we began this project, we assumed that the University of Chicago was a postemancipation institution. However, as the University of Chicago historian and Dean of its College John Boyer has shown, the deep ties between the university’s original Bronzeville campus and its current Hyde Park campus constitute a rich “inheritance” and give the university what he calls “a plausible genealogy as a pre-Civil War institution.” Continuities between the two campuses can be found almost everywhere among its trustees, faculty members, student alumni, donor networks, intellectual culture, institutional memory, distinctive architecture, library books, and, of course, the University of Chicago’s name itself. The two campuses would undoubtedly be deemed inseparable alter egos of one another. Boyer convincingly makes this case. What he seems to have missed, however, was that this pre-Civil War founding also came with a founding slaveholder who endures to this day—haunting the halls of the Hutchinson Commons.

Douglas Plaque in Hutchinson Commons at the University of Chicago (Courtesy of the Authors).

Due in no small part to the pioneering work of the Brown University Committee of Slavery and Justice and historian Craig Steven Wilder, we now know that the University of Chicago is not alone. Many elite colleges and universities have deep roots in American slavery. Many also owe their large endowments to the financial legacy of the slave economy. These schools continue to leverage these endowments to develop and recruit talented faculty and students, build up the physical plant, and maintain their global reputations in the marketplace of ideas. Once a school comes to grips with its historical ties to chattel slavery, however, what is its next step?

Many may argue that Georgetown University might provide a useful but incomplete starting point for the University of Chicago. Both schools are located in urban environments with a large African American population. Both are endowed with lots of money. Under the aegis of the Georgetown Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation committee, Georgetown has also publicly wrestled with the question of what it owes the descendants of the enslaved. Georgetown has decided that there is not a statute of limitations on slavery, and that to reckon with the past they had to engage historically. The university opened up four tenure track lines in African American Studies, expanded the African American Studies Major, and has plans to establish a Research Center for Racial Justice. In addition to these measures, the university will offer the descendants of enslaved African Americans sold by its friars preferential treatment in admissions (similar to the boost that so-called legacy students already receive). It will also rename two campus buildings in honor of African Americans—one an educator and another one of the enslaved who made the university a financial possibility. But is this enough?

Perhaps, instead, the University of Chicago can find a way to look beyond Georgetown and what many have rightly criticized as its self-congratulatory, self-serving, and extremely limited program. Given the University of Chicago’s location on the city’s South Side it is uniquely situated to engage and address the legacy of slavery in a much different way. Chicago, like Washington D.C., has long been one of the meccas of Black life and culture. Establishing an African American Studies department should be a no-brainer. So, too, should be a concerted effort to recruit and develop faculty of color while vigorously recruiting and mentoring underrepresented students to attend the university. But this should happen anyway. It’s not reparations.

Maybe a further step would be to encourage the University to build more deeply upon the community-based efforts it is already engaging in. These include the UChicago Promise program, which provides enrichment programs for talented but under-served public school students. There is also the Chicago Public Schools Educators Award Scholarship—a full scholarship to attend the University for the children of educators in the Chicago Public Schools—which should be broadly promoted and expanded. The University’s Arts + Public Life programming, including the Washington Park Arts Block, the Black Cinema House, and the Stony Island Arts Bank (led by the indefatigable Theaster Gates) should all continue to invite local residents to engage in their programming. But, again, this is already happening as it should.

Perhaps we’ve gotten reparations entirely backwards. Here we must return to Julie and the enslaved peoples of the Douglas plantation. Any program of reparations must begin with them and their descendants. Reparations that flow back to the university itself either in the form of goodwill or an improved campus experience are not reparations. Diversity initiatives, black studies programs, and slick PR campaigns celebrating the university’s benevolence function primarily to enrich the university while compelling black students and faculty members to labor once more for the institution that owes their ancestors money.

This cannot be a question of what the university will do for black communities. It must be a function of what black communities demand as payment to forgive an unforgivable debt. Black people do not need a seat at the university’s reparations table. They need to own that table and have full control over how reparations are structured.

As more details of the university’s participation in slavery, Jim Crow, and discrimination post-1967 are documented, the current residents and community organizations of the South Side of Chicago must lead the way—not be told where to sit. This is part of a requisite cognitive shift that involves thinking beyond the legal framework of ‘damages,’ or the neoliberal ordering of private property rights, or the monstrosity of capitalism. We must imagine an entirely new model of human interactions, self-governance, and social organization. One that shuns hierarchies and fosters horizontalism. If done correctly, reparations can lead the way to a fresh re-conceptualization of politics—not based in crude self-interest but justice and even love.

Reparations promise us a monumental re-birthing of America. Like most births, this one will be painful. But the practice of reparations must continue until the world that slavery built is rolled up and a new order spread out in its place. Until then, the University of Chicago must begin all of its conversations with the knowledge that it is party to a horrific crime that can never be fully rectified. But still it must try. And through that trying it must embrace an entirely new mission—one that centers slavery, the lives of the enslaved, and their descendants.

*This post is derived from a paper by the Reparations at UChicago Working Group (RAUC), which emerged from a recent session of the University of Chicago’s U.S. History Workshop on “Reparations and the Modern University.”

Ashley Finigan is a PhD Candidate in the History Department at the University of Chicago where she is also a Residential Fellow at the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality. She is currently at work on her dissertation, an organizational history of the National Council of Negro Women. Follow her on Twitter @ashfin.

Caine Jordan is a first-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. His work focuses on race, respectability, and racial uplift in the Civil Rights Movement.

Guy Emerson Mount is a Mellon Foundation Fellow at the University of Chicago and the coordinator of the U.S. History Workshop. His dissertation, “The Last Reconstruction: Race, Nation, and Empire in the Black Pacific,” examines the relationship between the end of American slavery and the birth of American overseas empire. Follow him on Twitter @GuyEmersonMount.

Kai Parker is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. His dissertation is titled “Redemption in the Godless City: Messianism and Black Chicago, 1930-1968” and explores the intersection of race, religion, and Civil Rights.

- J.J. Ligon to Mary Martin, May 1, 1859, Illinois Historical Library, Springfield, Ill as cited in Anita Watkins Clinton, “Stephen Arnold Douglas—His Mississippi Experience,” The Journal of Mississippi History Vol. L, No. 2 (May 1988), 30.

- Ibid.

- Chicago Press and Tribune, December 24, 1858.