Arrests of Children in Jerusalem: Detention, Education, Financial Strains and Social Burdens

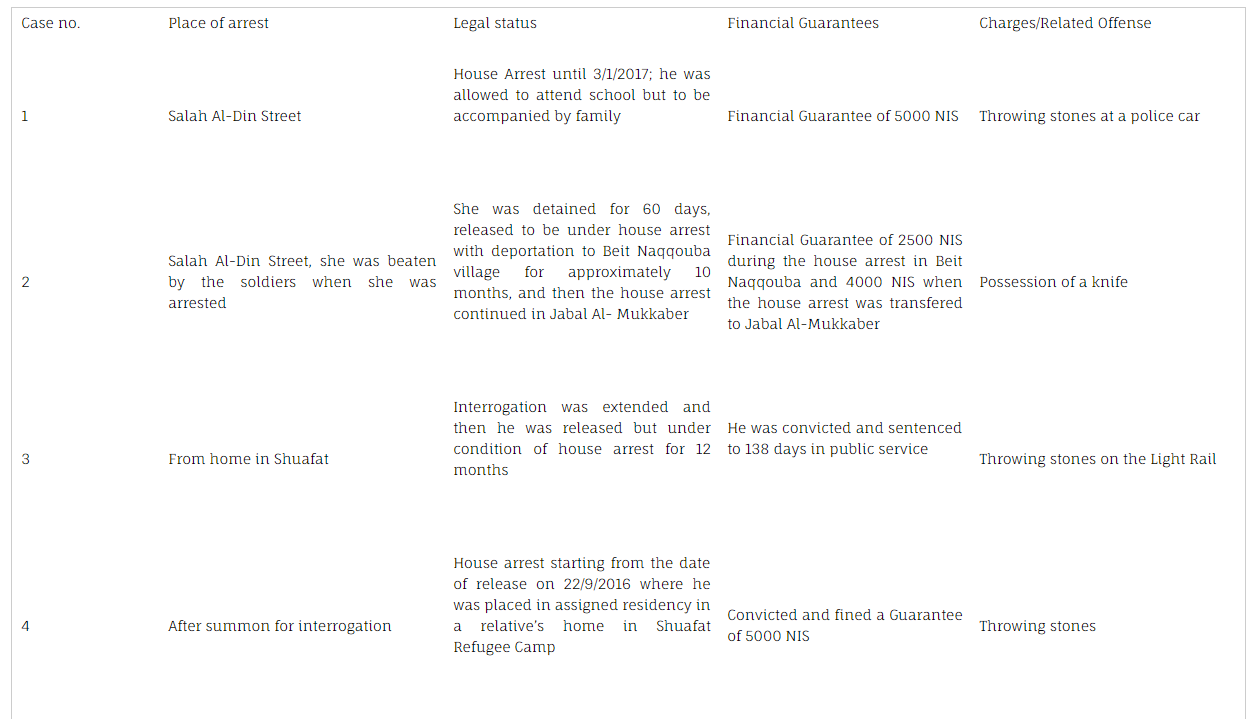

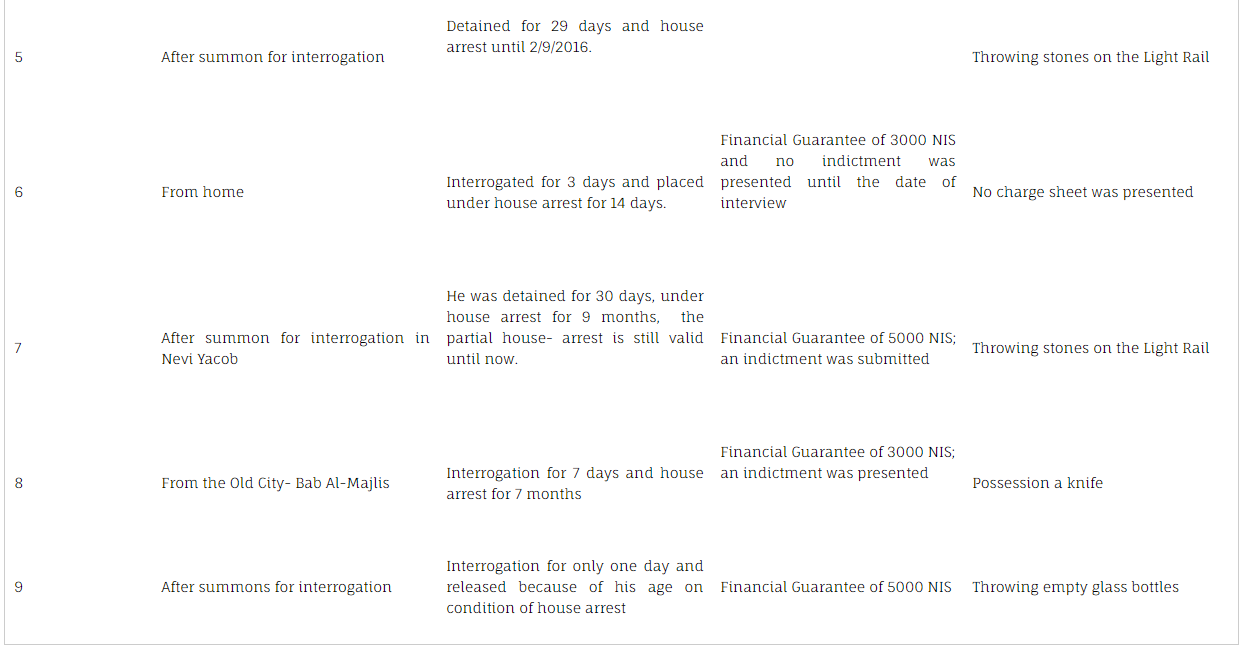

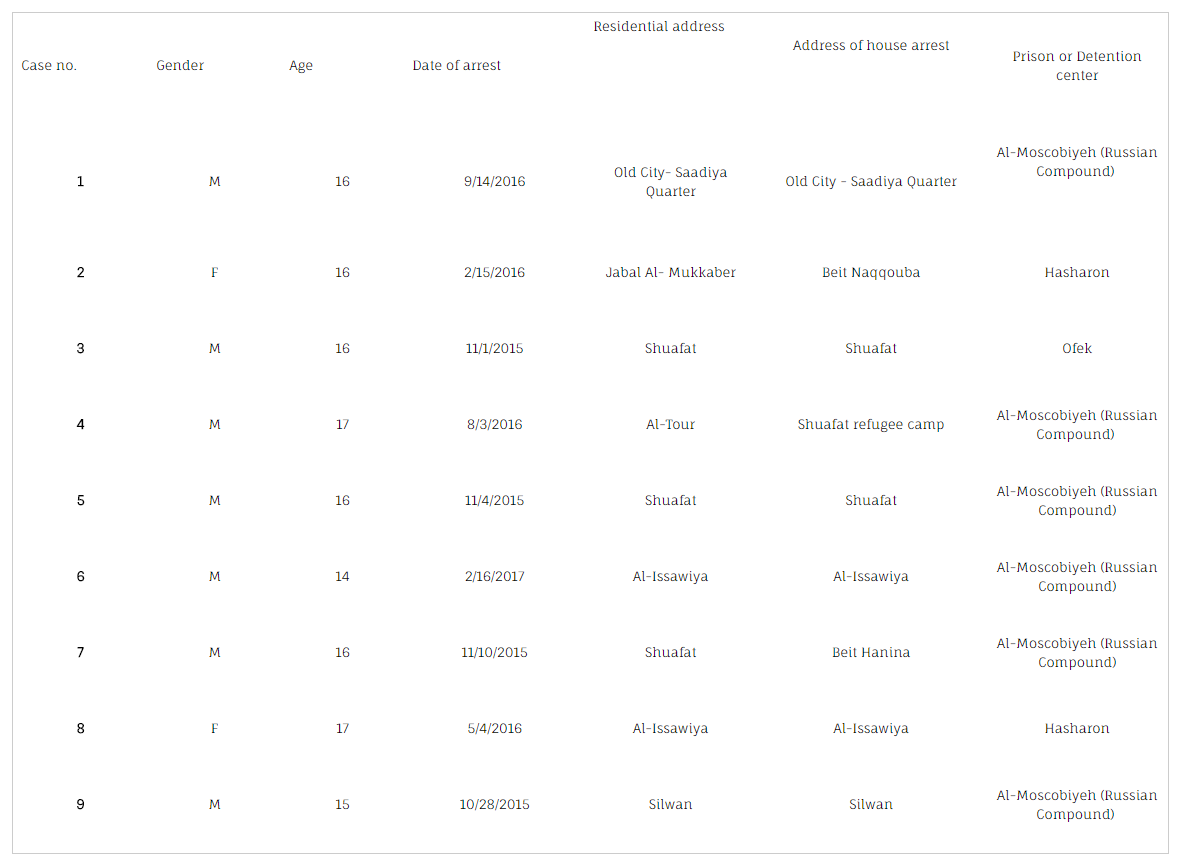

Based on Addameer’s [Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association] monitoring of 9 recent and current cases of Palestinian children from Jerusalem from the onset of 2017 who were arrested and, as well as exhaustive Addameer statistics and data from several years of monitoring and legal representation in Jerusalem, this factsheet will explore the effects of arrest and house arrest on a child’s education and development. The factsheet relies on information obtained through visit questionnaires, field visits, and court protocols.

The trends and data are based on 2015-2016 affidavits taken from Palestinian children from Jerusalem who experienced arrest by Israeli forces and were taken to Beit Alyaho Police Center, Oz police center, Salah Al-Din police station, and Qishleh police center, as well as Al-Moscobiyeh. Interrogation within these centers focused on confessions obtained through coercive methods, including physical violence, in the absence of their parents and attorneys. Despite the fact that the interrogation lasted for a few hours in some cases, some of the children were subjected to intense interrogation methods, slaps, beatings, kicking, and being cuffed by hands and legs to the chair. This factsheet aims to examine the aftermath, namely the policy of house arrest and the post-detention experience.

Legalities: No Last Resort for Palestinian Children in Jerusalem

The Convention on the Rights of the Child underlines in Article 27(b) that “No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily.” The article further underlines that in the case of arrest, “the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time”.

The Convention states in Article 2 the principle of best interest of the child, underlining that “in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration.” These best interests undoubtedly involve treating the children with dignity, freedom from cruel and degrading punishment, the ability to grow, especially through social development, and the pursuit of their education.

The central Israeli legislation that addresses the arrest and detention of children in Jerusalem is the Trial, Punishment and Modes of Treatment Law, 5731-1971 and namely Amendment 14, which took effect in 2009. While the amendment emphasizes the principle of arrest of children only as a last resort, in practice, Palestinian children are not afforded this principle, with systematic arrests and associated discriminatory practices being maintained as the norm. Palestinian children, for example, are more likely to be arrested than Israeli children, and when arrested, are more likely to be held under interrogation without access to their attorneys and parents. Defense for Children International – Palestine has observed through documentation that, “Israeli authorities implement the law in a discriminatory manner, denying Palestinian children in East Jerusalem of their rights from the moment of arrest to the end of legal proceedings.

Effects on Psychology, Development, and Education

“The minute of arrest in the early mornings at homes is the most fearful experience they went through so far in their lives, because they are waking them up while they are asleep, taking them from their bedrooms, their bed, handcuffing them, blind folding them in front of their parents…who are supposed to represent the protective ....”

- Nader Abu-Amsheh of the East Jerusalem YMCA Children Ex-Detainee Rehabilitation Program

Addameer research has confirmed that traumatic experiences of arrest and associated ill treatment result in symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), as well as disorientation, loss of control of self determination, and low self esteem. Due to the severe trauma resulting from interrogation and the associated feelings of being left behind from their peers, it has been observed that many ex-detainee children drop out of school.

It has been found that PTSD associated with the experience of arrest “adversely affect any future pursuit of education and are considered a major cause of former Palestinian child prisoners’ reluctance to return to school.” It has also been noted by Addameer that, “in addition to the ill-treatment and torture suffered by Palestinian children during the process of arrest, interrogation and detention, their social capital is also squandered as result of detention, negatively impacting their ability to grow into a valuable and autonomous individual.” Ultimately, this social regression inherently hinders empowerment, competence, and self-determination – factors crucial to a healthy growing environment for children.

Cases Monitored: Financial and Educational Losses

“In virtually all of the cases, the children would have the problem even after the child goes back to school in focusing because their education was obstructed for a significant period…. Ultimately they lose years or do not go back to school … the child is in school, leaves school for a while, does not want to go back.”

- Radi Darwish, Attorney monitoring child detention in Jerusalem

The educational costs of arrests and detention are profound. The children whose cases were surveyed lost periods ranging from 3 months, one semester, and one year of school, and two of the children chose not to return to school. Notably, three of these children missed a full year of school as a result of their arrest and house arrest. Extension of detention ranged from 1 day to 60 days (including after charges were submitted). A 16-year-old child, who was arrested from his home on 1 November 2015 in East Jerusalem and taken to Ofek Prison, was released conditionally on house arrest for 12 months. He was convicted of throwing stones on a light rail tram and sentenced to 138 days in public service. He lost a semester of school as a result of the house arrest (case no. 3).

In addition to the impact on education, the children’s families were also compelled to pay financial guarantees that ranged from 2500 and 5000 NIS (equivalent of approximately 700 and 1400 USD). However, the family of one child (case no. 2) was required to pay a financial guarantee of 2500 NIS as a condition of her release on house arrest in Beit Naqqouba and then subsequently 4000 NIS when the house arrest was transferred to Jabal Al-Mukkaber, totaling 6500 NIS. The indictment against her was submitted but no verdict ruling has been issued to date.

A female 16-year-old child was arrested on 15 February 2016 from Salah Al-Din Street after being beaten by Israeli forces. She was placed under house arrest under the condition of temporary residency away from her home. She was detained for 60 days and then placed under house arrest with residency assignment in Beit Naqqouba village for approximately 10 months, the house arrest then continued in Jabal Al-Mukkaber. Her family was ordered to pay a financial guarantee of 2500 NIS during the house arrest in Beit Naqqouba and 4000 NIS when the house arrest was transferred to Jabal Al-Mukkaber. Indictment against her was submitted but no verdict ruling has been issued to date.

According to Murad Amro, Clinical Psychologist at the Palestinian Counseling Center, house arrest impacts the child’s relationships, including those with their parents. It results in anxiety, feelings of helplessness, as well as psychosomatic symptoms of bodily pain. Amro explains that “the experience impacts their ability to maintain self-regulation and self-mastery, essential for psychological and social processes... It causes changes in dynamics of family relationships, and affects self-concept and self-esteem.” Amro explains that the associated reluctance to go back to school may be a form of rebellion and a cry of helplessness, as a result of “not being able to feel safe and not having their expectations of protection fulfilled. It may be that they are trying to resist being in a social system that does not give them protection.”

Notably, Palestinian children in Jerusalem are sometimes placed in assigned residency as a term of their house arrest. For example, in case no. 7, a 16-year-old Palestinian child from Shuafat, who was arrested on 11/10/2015, was placed under house arrest for 60 days in Beit Hanina. In case no. 2, a female child from Jabal Al-Mukkaber who was arrested on 2/15/2016 was placed under house arrest in Beit Naqqouba. In case no. 4, a 17-year-old male child from Al-Tour who was arrested on 8/3/2016 was placed under house arrest in Shuafat refugee camp in an assigned residency with a relative. The impact of these particular house arrests is that they remove the child from their surroundings and environment to the child’s detriment.

According to Clinical Psychologist Murad Amro, these types of assigned residency situations may have profound impacts. Amro explains, “this is a particularly stressful factor for the family and the child to manage this period of separation and to support the child during this situation. Guilt-feeling and blaming are very important here, for the child and the parents. The child will be blaming the family for not being able to protect the child…arrest makes the child feel guilty, loss of locus of control.”

Conclusion: Obstructing Development and Education

The continued policy of arrests of Palestinian children in Jerusalem contravenes the Convention on the Rights of the Child in its use not as a last resort as stated in article 37 of the Convention. The associated disruption of education and social development unarguably violate the best interests of the child. The policy also breaches the State’s responsibility to make primary and secondary education accessible to the children (article 28). Furthermore, the Convention affirms, “in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” The practice of arrest and detention of Palestinian children in Jerusalem may be seen as a larger policy of repression and disruption of a population, resulting in the obstruction of social development, the impeding of education, associated financial burdens, and sometimes, relocation outside of his or her home environment in assigned residency.

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html [accessed 29 May 2017]

Ibid.

Ibid.

Defense for Children International, 11 August 2016. “New Israeli Law allows Children as Young as 12 to be Jailed” http://nwttac.dci-palestine.org/new_israeli_law_allows_children_as_young_as_12_to_be_jailed

Nader Abu Amsheh, interviewed by Bill Skidmore. Beit Sahour, 3 January 2015. Interviewed for “In the Shadow of the 2014 Gaza War: Imprisonment of Jerusalem’s Children,” Addameer, 2016. Available at http://www.addameer.org/sites/default/files/publications/imprisonment_of...

Addameer, 2010. “The Right of Child Prisoners to Education”. Available at http://www.addameer.org/sites/default/files/publications/addameer-report-the-right-of-child-prisoners-to-education-october-2010-en.pdf

Ibid, 11.

Ibid.

Interview with Addameer on 30 May 2017. Ramallah.

Ibid.

ADDAMEER (Arabic for conscience) Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association is a Palestinian non-governmental, civil institution that works to support Palestinian political prisoners held in Israeli and Palestinian prisons. Established in 1992 by a group of activists interested in human rights, the center offers free legal aid to political prisoners, advocates their rights at the national and international level, and works to end torture and other violations of prisoners' rights through monitoring, legal procedures and solidarity campaigns.