Let Black Kids Just Be Kids

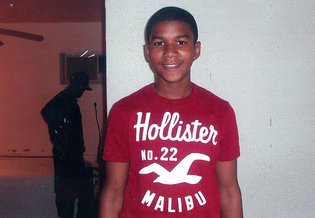

George Zimmerman admitted at his 2012 bail hearing that he misjudged Trayvon Martin’s age when he killed him. “I thought he was a little bit younger than I am,” he said, meaning just under 28. But Trayvon was only 17.

What may be most tragic about Mr. Zimmerman’s miscalculation is that it’s widespread. To many people, black boys seem older than they are: In one study, people overestimated their ages by 4.5 years. This contributes to a false perception that black boys are less childlike than white boys.

Black girls are subject to similar beliefs, according to a recent study by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality. A group of 325 adults viewed black girls as needing less nurturing, support and protection than white girls, and as knowing more about sex and other adult topics.

People of all races see black children as less innocent, more adultlike and more responsible for their actions than their white peers. In turn, normal childhood behavior, like disobedience, tantrums and back talk, is seen as a criminal threat when black kids do it. Social scientists have found that this misperception causes black children to be “pushed out, overpoliced and underprotected,” according to a report by the legal scholar Kimberlé W. Crenshaw.

That’s why we must create a future in which children of color are not disproportionately caught up in the criminal justice system, a world in which a black 17-year-old can wear a hoodie without being assumed to be a criminal.

Creating that social change, however, has proved difficult. And that’s partly because the concept of childhood innocence itself has a deep and disturbing racial history.

By understanding this history, we can learn why anti-racist strategies have hit some surprising limits, and devise tactics to confront or even avoid those roadblocks in the future.

The association between childhood and innocence did not always exist. Before the Enlightenment, children in the West were widely regarded as immodest beings who needed to be taught to restrain themselves. “The devil has been with them already,” the Puritan minister Cotton Mather wrote of babies in 1689. They “go astray as soon as they are born.”

In some religious traditions, children, as much as adults, were understood to bear original sin. Benjamin Wadsworth, a powerful Colonial-era minister, described children in 1720 as “sharers in the guilt of Adam” who have a “naturally sinful and guilty state.”

Enlightenment thinkers had different ideas: John Locke suggested that children were blank slates, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau portrayed them as connected to nature. The poet William Wordsworth imagined children as holy innocents who could lead adults to God. Rising forms of Christianity de-emphasized the idea of original sin.

While earlier generations had viewed children as miniature adults, 19th-century sentimentalists increasingly identified innocence as the single most important quality that distinguished children from their elders. By the mid-19th century, the ideas of childhood and innocence had merged. From then on, innocence defined American childhood.

But only white kids were allowed to be innocent. The more that popular writers, playwrights, actors and visual artists created images of innocent white children, the more they depicted children of color, especially black children, as unconstrained imps. Over time, this resulted in them being defined as nonchildren.

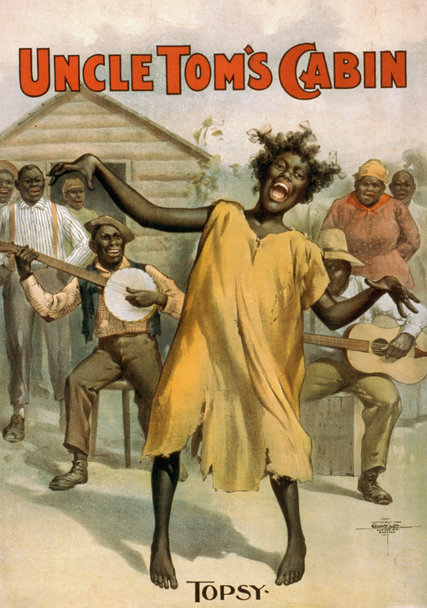

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” one of the most influential books of the 19th century, was pivotal to this process. When Harriet Beecher Stowe published her novel in 1852, she created the angelic white Eva, who contrasted with Topsy, the mischievous black girl.

Stowe carefully showed, however, that Topsy was at heart an innocent child who misbehaved because she had been traumatized, “hardened,” by slavery’s violence. Topsy’s bad behavior implicated slavery, not her or black children in general.

The novel’s success prompted theatrical troupes across the country to adapt “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” into what became one of the most popular stage shows of all time. But to attract the biggest audiences, these productions combined Stowe’s story with the era’s other hugely popular entertainment: minstrelsy.

Topsys onstage, often played by white women in blackface, were adultlike, cartoonish characters who laughed as they were beaten, and who invited audiences to laugh, too. In these shows, Topsy’s innocence and vulnerability vanished. The violence that Stowe condemned became a source of delight for white theater audiences.

This minstrel version of Topsy turned into the pickaninny, one of the most damaging racist images ever created. This dehumanized black juvenile character was comically impervious to pain and never needed protection or tenderness.

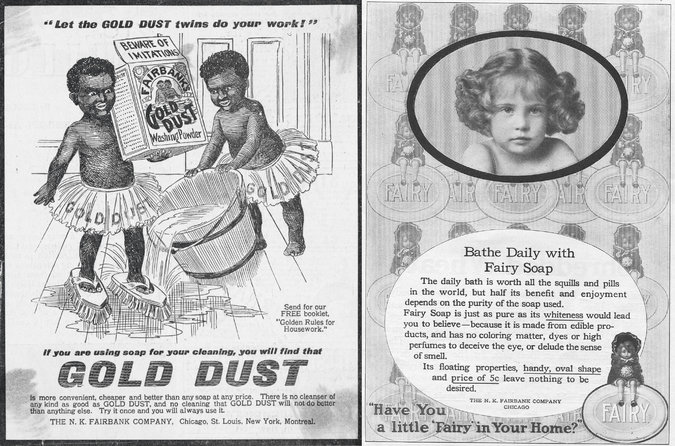

The racist caricature of the pickaninny often appeared alongside cherubic white children. For example, advertisements run in the early 1900s by the Fairbank Company, which sold cleaning and cooking products, featured the “Gold Dust Twins,” who were seminude, ungendered, ink-black juveniles. The advertising copy read, “Let the Gold Dust Twins do your work.”

Fairbank ran that ad alongside one for Fairy Soap, whose mascot was a serene white child dressed in fancy clothes. Fairy Soap, the advertisement declared, “soothes and softens the tenderest skin.” In these paired advertisements, which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal and many other magazines, black nonchildren toil while white darlings receive tender caresses.

These images weaponized childhood innocence, transforming it into a tool of racial domination.

But black activists did not acquiesce to this power play. From the first moments when Topsy devolved into the pickaninny, African-Americans worked to counter the libel that their kids were not vulnerable and not really children.

In 1855, Frederick Douglass made exactly this point in “My Bondage and My Freedom” when he asserted, “Slave children are children.”

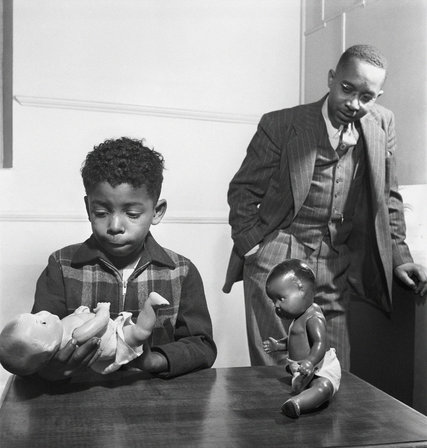

In the next century, key players in the civil rights movement made childhood innocence central to anti-racist causes. In 1939, the psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark introduced the “doll test,” in which black children, when confronted with their own preference for white dolls, burst into tears.

The Clarks’ findings hit a nerve in part because they used symbols of innocence, dolls and sobbing children, to display the effects of racism. The Supreme Court leaned on these doll tests in its Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which outlawed segregation in public schools in 1954.

The next year, Mamie Till juxtaposed the bloated, pulverized body of her murdered son Emmett with a photograph of him as a smiling schoolboy. The lynchers had defined Emmett as a sexual threat, but his mother made America see him as a kid.

In these cases, black activists captured the political power of childhood innocence, which had previously supported white supremacy, and repurposed it for a civil rights agenda.

But there’s a catch. As the poet and feminist theorist Audre Lorde wrote: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” This is exactly the case with anti-racist uses of childhood innocence.

The Clarks, Mamie Till and others used childhood innocence to make important political gains, but their use of the “master’s tools” ultimately could not erase the racial connotations of childhood innocence itself. And so studies continue to show that black children are seen as less innocent and more adultlike than their white peers.

As long as white children are constructed as innocent, we must continue to demand that children of color are as well. Because the idea of childhood innocence carries so much political force, we can’t allow it to be a whites-only club.

The problem, however, is that every time we insist that the gates of innocence open to children of color, we limit ourselves by language, a “frame,” as the linguist George Lakoff would say, that is embedded in racism. When we argue that black and brown children are as innocent as white children, and we must, we assume that childhood innocence is purely positive. But the idea of childhood innocence itself is not innocent: It’s part of a 200-year-old history of white supremacy.

It’s time to create language that values justice over innocence. The most important question we can ask about children may not be whether they are inherently innocent. Instead: Are they are hungry? Do they have adequate health care? Are they free from police brutality? Are they threatened by a poisoned and volatile environment? Are they growing up in a securely democratic nation?

All children deserve equal protection under the law not because they’re innocent, but because they’re people. By understanding children’s rights as human rights, we can begin to undermine the political power of childhood innocence, a cultural formation that has proved, over and over, to be one of white supremacy’s most potent weapons.

[Robin Bernstein, a professor of African-American studies at Harvard, is the author of “Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood From Slavery to Civil Rights.”]