Karl Marx Makes a Comeback

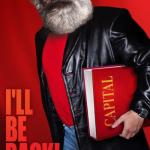

Several months ago the Communist party in Russia updated their visual propaganda by giving three of their most controversial icons—Lenin, Stalin, and Karl Marx—a makeover. In their new poster series, Stalin looks handsome and serious in a puff of vaping smoke; Lenin looks like a college student or a hacker, hunched over a bright red laptop; and Marx looks like a rock star in a red t-shirt and a black leather jacket. Marx has a copy of Das Kapital tucked under one arm and is vowing, “I’ll be back.”

Ironically, Marx really is back and not just in Russia. Since the global financial collapse of 2008 Marx has become a pop icon across the globe. His image can be found graffitied throughout the world as well as on t-shirts, and mugs. Marx is for sale in a number of unusual forms, including a piggy bank and floating Marx head stickers, while in Germany you can get a credit card with Marx’s face on it, and in Japan you can buy a set of Mountain Man action figures based on Marx, Mao, Lenin, and Thoreau.

Over the last decade, Marx has also made a comeback as a serious intellectual figure. In the fall of 2008, as the global financial crisis was starting to be felt and understood, The Guardian reported on the increasing demand for his books: “‘Marx is in fashion again,’ said Jörn Schütrumpf, manager of the Berlin publishing house Karl-Dietz which publishes the works of Marx and Engels in German. ‘We’re seeing a very distinct increase in demand for his books, a demand which we expect to rise even more steeply before the year’s end.’”

Two best-selling biographies have also appeared, Mary Gabriel’s Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution (2011), a stunning, page-turning re-evaluation of Marx that incorporates much of his family life, as well as Jonathan Sperber’s Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life (2013), which makes the argument—belied by the popularity of the biography itself—that Marx was more important to his own time than to ours.

In his widely-read book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), the French economist Thomas Piketty – himself sometimes hailed as a modern-day Marx – encourages economists to “take inspiration from example.” Meanwhile, David Harvey, a mild mannered CUNY professor, has achieved cult status with his popular online lectures that help the average reader make their way through the hundreds of pages of Marx’s Capital, volumes 1-3.

What’s driving this resurgence of interest in Marx, as kitsch but especially as a serious thinker about economics, class, and inequality? I see a few factors here.

1) The global financial collapse of 2008 made Marx’s critique of capitalism look fresher than ever. Marx predicted cycles of collapse and consolidation, and his analysis explains how inequality deepens during times of capitalist crisis. His predictions have played out as we have seen the top .1% profit from the housing collapse of 2008 while the rest of us have suffered. In the lead up to the election last year, for example, Trump was accused of having cheered on the housing crisis of 2008, because it meant that he and his cronies could buy up scads of cheap real estate that have since risen significantly in value.

2) The collapse of Communist regimes, from the USSR, to the capitalist makeover of China, to the opening of Cuban borders, has everyone proclaiming the death and failure of communism as a political and societal toolkit. Ironically, it may be that if communism is less of a world-wide threat, then Karl Marx, as the official godfather of communism, is seen as less threatening as well.

3) The post-Cold War generation views socialism and communism more favorably than during any time since the Cold War A scholar at Tufts University has hypothesized that millennials, born into the worst job market since the Great Depression, are more skeptical of capitalism than their parents. According to this same researcher, millennials see Scandinavian countries as models for democratic socialism, rather than current or former communist countries like Russia and China.

Whatever the reasons, Marx’s comeback coincides with his impending bicentennial. On May 5, 2018, Karl Marx will be 200 years old and his magnum opus, Capital, will be 151.This year and next there are tributes and celebrations for both Capital and its author across the globe. York University held a celebration of 150 year of Capital last May with scholars from around the world; Trier, where Marx was born, is planning an entire year of events as is the Marx Memorial Library in London. This Berlin based website, Marx200, is keeping a running tally of these events and adding to them daily.

Here in Pittsburgh, at Carnegie Mellon University’s Humanities Center, we are taking stock with our own year of events. Marx@200, running from the fall of 2017 through the summer of 2018 will feature lectures, workshops, performances, an art show, a symposium, and a conference. The celebration kick-offs on Thursday, September 14th with the Mid-Atlantic premier of The Young Karl Marx, a film by the Haitian director Raoul Peck, who was nominated for an Oscar for I am Not Your Negro. You can keep tabs on what we’re doing here.

For the last 60 years Marx, communism, and socialism have gotten a pretty bad rap across the West. Marx has been seen as an apologist for the kinds of imperialism, genocide, and repression in communist countries over the last 100 years, even though The Communist Manifesto provided a synthesis of the revolutionary European thought of 1848— not a blueprint for totalitarianism.

But capitalism, it would seem, has outdone itself in the 21st century. Inequality is worse than ever before, and the US is ruled by a capitalist oligarchy. Suddenly, Marx is cool again, but mainly because he was, and remains today, one of capitalism’s most astute critics. Happy Birthday Karl, and thanks.

Kathy M. Newman is Associate Professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University and also a regular blogger for The Center for Working Class Studies.