Lynching and Antilynching: Art and Politics in the 1930s

The term “lynching” supposedly originated during the American Revolution with Colonel Charles Lynch, a VA justice of the peace. Lynch ordered “extra legal punishment” for British Loyalists, hanging without a trial. From this period we have the terms Lynch’s Law and lynching.

Lynching became an important subject for visual artists in the 1930s. During the Depression, antilynching works were first a reaction to the wide spread outrage over the Scottsboro case and then part of the political and legislative efforts to make lynching a federal offence. In early 1935, both the NAACP and the Communist Party’s John Reed Club held competing art exhibitions that not only condemned lynching but also supported their legislative objectives.

Lynching became a fact of American life after the Civil War when slavery was abolished. However racial terror lynching emerged in the late nineteenth century, and continued until the middle of the twentieth century as a vicious tool of racial control. Racial terror was in fact a way to reestablish white supremacy, suppress and control black communities. This was especially advocated by the K.K.K as they terrorized the black communities throughout the South.

The historical reality of lynching was far more complex and more horrifying than any literary or visual account. Lynching victims were mostly black but also women and children. Few victims were “strung up” in a hurry. Many persons were tortured first and men were castrated and many burned. The great majority of the victims were taken from town or city jails and were killed with the complicity or help from law enforcement officers. Lynchings were not held in secret but were announced well ahead of time by the press and radio and they were attended by large crowds who witnessed the cruelty in a carnival like atmosphere. It was in the rural areas of the South where the most savage lynchings took place. Lynching, unlike murder, was often a crime in which the guilt was so widespread that prosecution was virtually impossible. The mob included onlookers of men, women and children.

In the 1920s the Communist Party (CP) began to change from its focus on labor problems to a more political agenda especially in the South.The CP encouraged interracial organizing against lynching and antiracist activism throughout the 1930s.Interracial organizing helped to spur white artists to take up antilynching themes in their works. By the 1930s the CP of the U.S. needed only to seize upon and publicize some great injustice. That great racial cause celebe of the period was the Scottsboro case. It was ideal for the CP to begin their antilynching campaign. The Scottsboro case began in March 1931 and centered around 9 black boys who were falsely accused of raping two white women on board a train near Scottsboro, Alabama. These nine black boys became known in press and around the world as the Scottsboro Boys.

They all pleaded not guilty but they were still indicted by the grand jury. The trial was a sham and eight of the boys were sentenced to death but they were never executed. This was truly a “legal lynching”. There were many trials over many years with international publicity and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1937. The lives of the Scottsboro Boys were saved though it was almost twenty years before the last defendant was released from prison. In 1976 the governor of Alabama finally pardoned the last of the Scottsboro Boys.

Prentiss Taylor’s Scottsboro Limited, 1932 print was published along with a poem and play by Langston Hughes as a protest against the travesty of the trial of the Scottsboro boys.

Artists responded to the publicity generated by the Scottsboro case and letters were written asking them to produce images of lynching subjects in all media. The NCAA collected these images and an exhibition was held in early 1935. Many of these images portrayed the horror of lynching in a no-holds bar fashion hoping to shock the public into action and demand an antilynching bill be passed by Congress.

A second exhibition at that time was developed by leftist members of the Artists’ Union and several Communist-affiliated organizations including the John Reed Club. They advocated more radical antilynching legislation. They demanded the death penalty for the lynchers and connected the abolition of lynching to broader efforts to expand African American civil equality.

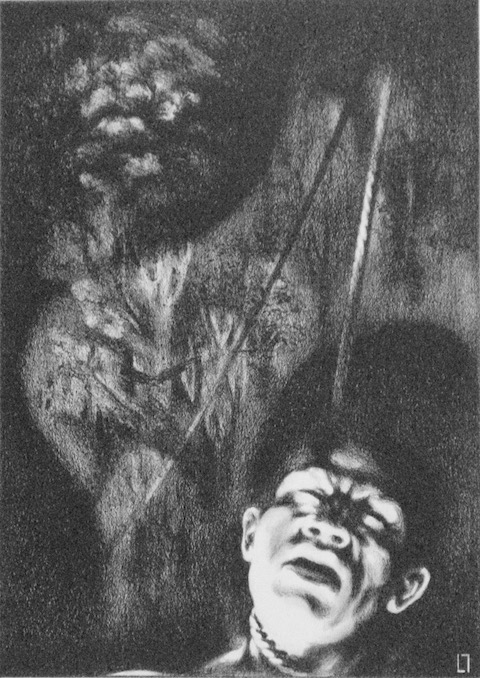

"Lynch Law" by Louis Lozowick 1936

Louis Lozowick was a member of the John Reed Club. He was so outraged by the lynchings that he produced the print Lynching (Lynch Law), 1936 which is a self-portrait. It was important for him to produce this image to combat racial injustice and African American victimization.

One of the important antilynching works was a poem written in 1937 by Abel Meeropol, a left-wing New York teacher, titled Strange Fruit. It protested American racism, particularly the lynching of African Americans. The words are a metaphor linking the tree’s fruit with lynching victims. The poem was set to music and was performed as a protest song in New York City in the late 1930s. A number of prints were produced during this time and later with the same title including one by Valerie Maynard, Strange Fruit, c.1960.

According to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama their reliable records from 1882 through 1965 indicated there were nearly 5,000 persons lynched. During this period there were over 200 attempts to pass antilynching laws in Congress and each time it was defeated by conservative Southeners. Finally in 1968 Congress enacted a section of the Civil Rights law that established federal protections against lynching.

The lynchings of the past are still with us today only in a different form. Black communities across the country are the scenes of mass incarcerations and the disproportionate sentencing of people of color as well the indiscriminate shooting by the police of black persons that we see and hear about too frequently.

Ref: Park, Marlene. “Lynching and Antilynching:Art and Politics in the 1930s. Prospects: 18,1993 Langa, Helen. “Radical Art, Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York”. University of California Press, 2004 Painter,N. Irvin. “Creating Black Americans, African American History and it’s Meaning, 1619 to the Present”. Oxford University Press, 2006

To view the prints in this exhibit please click here