JFK Had Ordered Full Withdrawal From Vietnam: Solid Evidence

The Ken Burns/Lynn Novick documentary series on Vietnam, currently airing on PBS, skates very lightly over one of the war’s most contentious questions: Did John F. Kennedy intend to pursue the fight or to pull out?

The second program alludes almost in passing to a withdrawal plan in 1962, conditioned on a then-optimistic assessment of how the war was going. But it also reports Kennedy’s qualms, expressed to a friend, as “We don’t have a prayer of staying in Vietnam. Those people hate us. They are going to throw our asses out of there at any point. But I can’t give up that territory to the communists and get the American people to re-elect me.” From this point, the program moves quickly to events in Saigon, to the November 1, 1963 South Vietnamese coup, and to Kennedy’s own assassination three weeks later.

But this presentation is highly misleading. In fact, Kennedy’s feelings about Vietnam went beyond mere qualms: he had already reached a decision and acted on it. In National Security Action Memorandum 263, dated October 11, 1963, Kennedy articulated his decision to withdraw all US military forces from Vietnam by the end of 1965 — with the withdrawal to be completed after the 1964 election. This was the formal policy of the United States government on the day he died.

Evidence of JFK’s Decision to Withdraw from Vietnam.

The evidence is massive and categorical. It includes:

- Robert McNamara’s instructions to the May 1963 SecDef Conference in Honolulu to develop the withdrawal plan.

- A detailed account of the McNamara-Taylor mission to Vietnam that returned with the withdrawal plan, drafted in their absence in the Pentagon by a team under Kennedy’s direct control.

- An audiotape of the discussion at the White House that led to the approval of NSAM 263 (National Security Action Memorandum), which implemented the plan; this audio was released by the Assassination Records Review Board at my request.

- The precise instructions for withdrawal delivered by Maxwell Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to his fellow Chiefs on October 4, 1963, in a memorandum that remained classified until 1997.

Taylor wrote:

“On 2 October the President approved recommendations on military matters contained in the report of the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The following actions derived from these recommendations are directed: … all planning will be directed toward preparing RVN forces for the withdrawal of all US special assistance units and personnel by the end of calendar year 1965. The US Comprehensive Plan, Vietnam, will be revised to bring it into consonance with these objectives, and to reduce planned residual (post-1965) MAAG strengths to approximately pre-insurgency levels… Execute the plan to withdraw 1,000 US military personnel by the end of 1963…”

False Narratives.

Why do so few Americans know that President Kennedy, a few weeks before his assassination, had decided to get the US military out, and avert what would later become the “quagmire” of a full-scale American war in Vietnam?

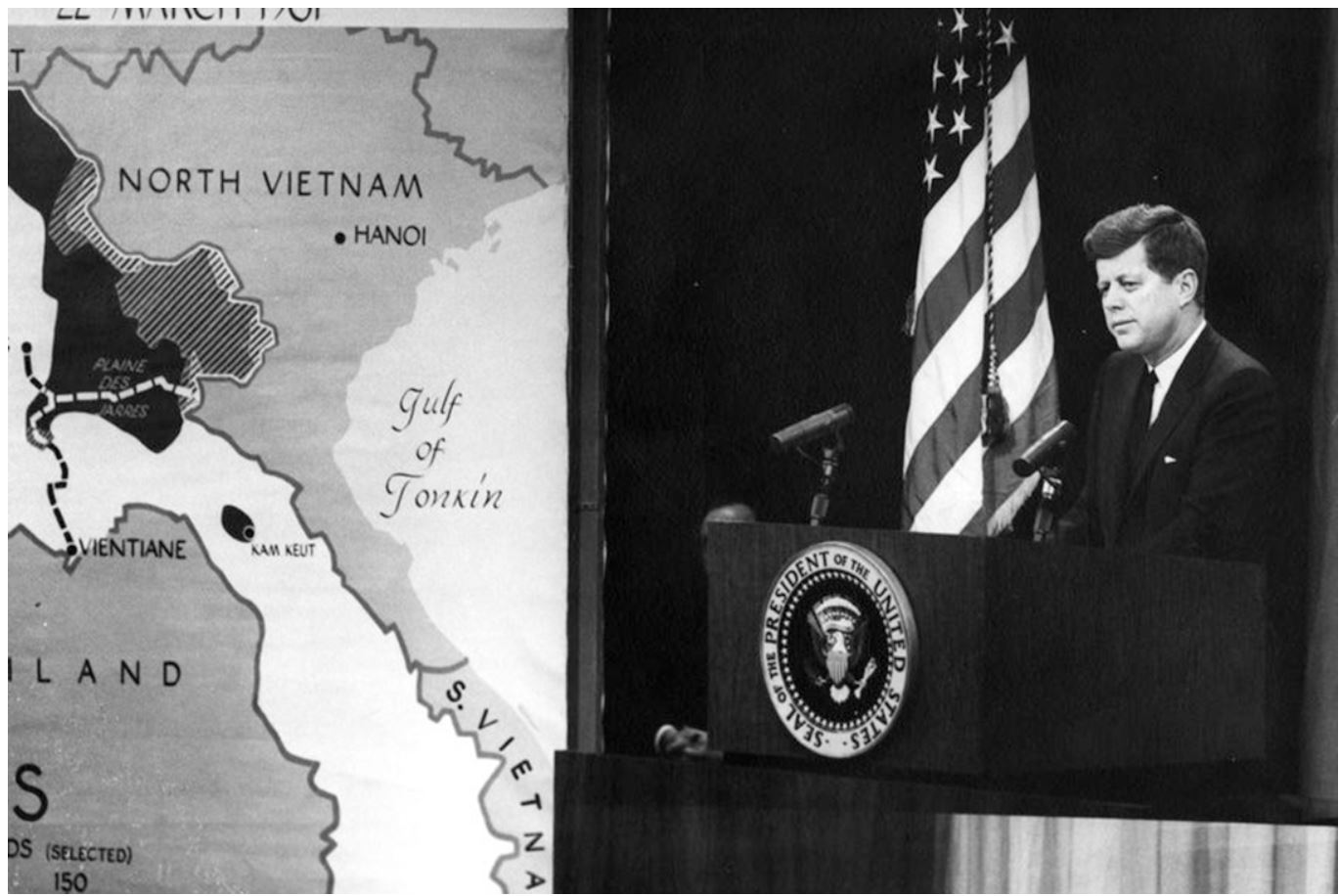

President John F. Kennedy press conference, State Department Auditorium, March 23, 1961. Photo credit: JFK Library

Because for three decades following these events, many historians adopted a false narrative which assumed an absolute continuity in policy between Kennedy and Johnson. By no coincidence, this was the line of the government at the time.

But a small minority of historians — beginning with Peter Dale Scott in 1972, followed by John Newman in his 1992 book JFK and Vietnam — were able to tease out the truth from the record. Their work was supported by a key witness, Robert McNamara, in his 1995 memoir In Retrospect.

The historian Fredrik Logevall has provided a chapter to the companion volume for The Vietnam War. [The Vietnam War: An Intimate History by Geoffrey C. Ward, Burn’s collaborator.] Logevall does not acknowledge the withdrawal plan, although he gives the following personal view:

“…the better argument is that JFK most likely would not have Americanized the war, but instead would have opted for some form of disengagement, presumably by way of a face-saving negotiated settlement.”

This is an improvement over the long-standing official story, but still misleading. Logevall states that “withdrawal theorists” have made their judgments “hastily,” with “evident reluctance,” based on “scant hints” in the documentary record.

In fact the record is rich and decisive. The issue has been debated many times. I would refer readers seeking a full account to the second edition of Newman’s JFK and Vietnam, which appeared in 2017 after a hiatus of 25 years following suppression by the publisher of the original book.

A good summary of arguments is Virtual JFK, an account of the 2005 Musgrove conference of historians and participants on this matter. My articles appeared in Boston Review and Salon. For those who would like a compressed version, I reproduce my letter to the New York Review of Books, dated December 6, 2007.

“A presidential decision requires a plan. The elements of a decision must include: (a) previous planning, reflected in military documents in this case; (b) discussion of the plan; (c) a decision to accept or reject the plan, reflected in a decision document; and (d) steps to implement the plan. In the case of JFK and withdrawal from Vietnam, all these elements are present.

“We have records of the 8th Secretary of Defense conference in Honolulu on May 6, 1963, which tell of a ‘Comprehensive Plan’ for Vietnam, including: ‘plan to withdraw 1000 US personnel from RVN by December 1963.’ McNamara also ordered that ‘training plans’ be developed for the Vietnamese to permit ‘a more rapid phase-out’of the remaining US forces.

“On October 2, 1963, these plans were discussed at the White House. We have the tape. McNamara states to Kennedy: ‘And the advantage of taking them out is that we can say to the Congress and the people that we do have a plan for reducing the exposure of US combat personnel to the guerilla actions in South Vietnam.’

“On October 5, 1963, at a meeting at 9:30 AM, Kennedy made the formal decision to implement the withdrawal plan. Again, we have the tape. On October 11, the White House issued National Security Action Memorandum 263, which speaks of ‘the implementation of plans to withdraw’ troops from Vietnam.

“A memorandum conveying the decision, from JCS Chair Maxwell Taylor to his military colleagues, had already been sent. It states: ‘All planning will be directed towards preparing RVN forces for the withdrawal of all US special assistance units and personnel by the end of calendar year 1965. The US Comprehensive Plan, Vietnam, will be revised to bring it into consonance with these objectives….’ ”

As a coda, the distinguished economist Francis Bator replied to my letter on January 17, 2008. Bator had served Lyndon Johnson as Deputy National Security Advisor; he cannot be accused of being what Logevall calls a “withdrawal theorist.” Bator’s opening sentence: “Professor Galbraith is correct that ‘there was a plan to withdraw US forces from Vietnam, beginning with the first thousand by December 1963, and almost all of the rest by the end of 1965…. President Kennedy had approved that plan. It was the actual policy of the United States on the day Kennedy died.’”

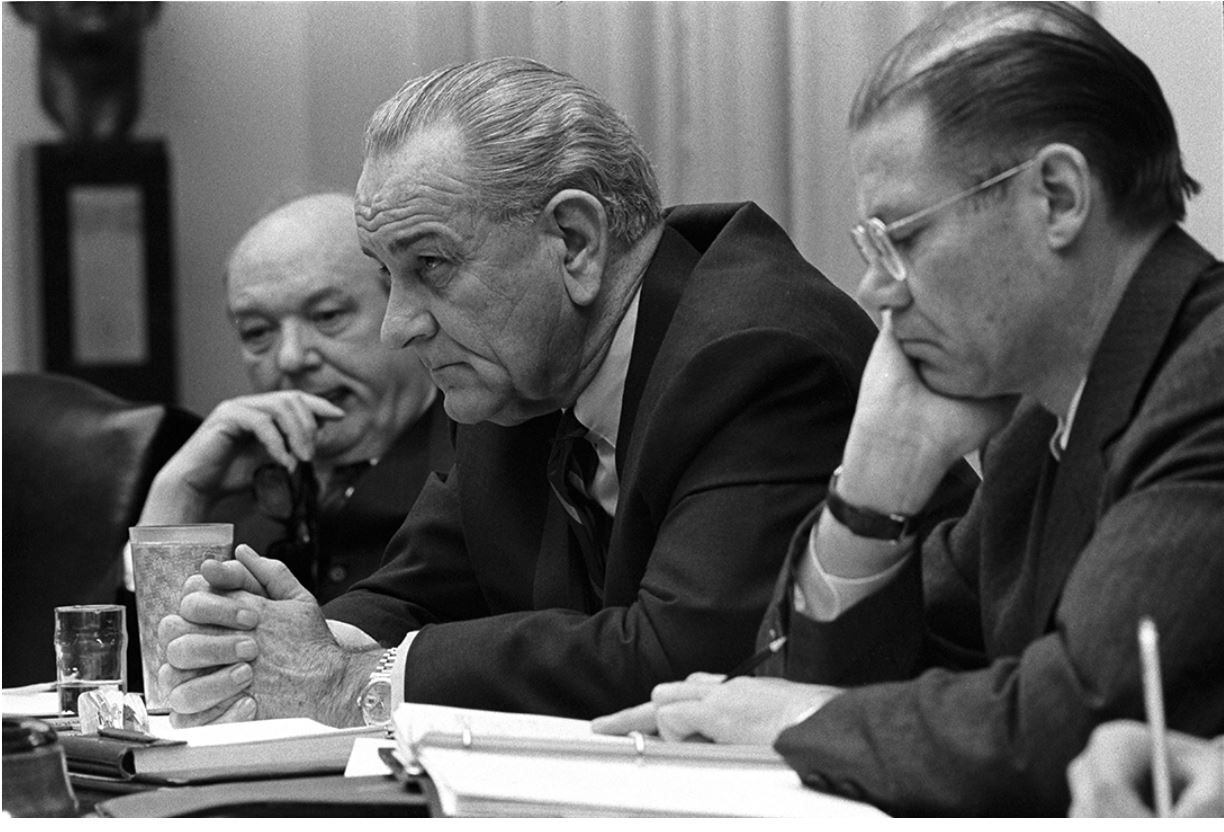

Secretary of State Dean Rusk, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara at a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House, February 9, 1968. Photo credit: The White House / Wikimedia

To be fair, Bator goes on to argue that the plan was conditional on military success — the same caveat offered by Burns and Novick in the documentary series when they refer to a 1962 withdrawal plan. But this is a case that McNamara contradicts and Newman has rebutted in detail.

There was no full withdrawal plan as yet in 1962, although Kennedy remained firm throughout that combat troops would not be sent, and he did instruct McNamara to develop a plan to remove the advisers who were there. McNamara — portrayed in the PBS film as the villain technocrat, a role that he played all too well — actually agreed that US forces should be withdrawn, whether or not the war could be won.

The full development of the plan, including the final timetable, came during the summer of 1963. By that time, official reporting — previously falsely optimistic — came into line with Kennedy’s own understanding, as he expressed it, that “we don’t have a prayer.”

As of October 2, 1963, the decision had been made. The plan existed. It had been approved. It had even been announced, albeit low-key, and by McNamara rather than Kennedy himself.

Could it have been reversed later? Yes. But Kennedy gave no sign of wavering in the few weeks that remained to him, despite the Saigon coup. And he could not in 1965 have faced the same dilemma that Lyndon Johnson did when, following the Tonkin Gulf incident, the North Vietnamese began to escalate the war. With withdrawals having progressed through 1964, only a small force would have been left by then. It would have been in Hanoi’s interest to wait until they were all gone, and the North Vietnamese leadership was nothing if not patient. And even if the Vietnamese had not waited, the die, by that time, would have been cast.

When Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency, many things were different, immediately. To get Kennedy’s role right is not to demonize LBJ, even though Johnson’s decisions led to catastrophe for Vietnam and for America, including for Johnson’s dream of the Great Society. But LBJ’s actions in Vietnam cannot be understood without first understanding what Kennedy did, and how policy stood on the day he was killed.

James K. Galbraith is a professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin.

Where else do you see journalism of this quality and value?

Please help WhoWhatWhy do more. Make a tax-deductible contribution now.