Taking Back Power: Public Power as a Vehicle Towards Energy Democracy

Asthma rates are so bad from the toxic emissions that many students cannot make it through gym class without their inhalers. Cancer and infant mortality rates in the area are through the roof.

These plants are owned by some of the biggest names in the utility business including groups like Duke Energy and AEP. Gibson Power Plant, the worst of them all, emits 2.9 million pounds of toxic compounds and 16.3 million metric tons of greenhouse gases a year. What’s more, most of the energy generated in these plants is transported out of state, leaving Indiana with all the emissions and very little gain.

Indiana’s power plants provide a window into how our current electrical system works. It is a system dominated by a small number of large powerful companies, called investor-owned utilities. Their centralized fossil fuel plants are at the heart of our aging electricity grid—a core contributor to rapidly-accelerating climate change.

The carbon emissions associated with these power providers are but one symptom of larger systemic issues in the sector. Investor-owned utilities are traditionally profit-oriented corporations whose structures are based on an paradigm of extraction. Following the path of least resistance, they often burden communities who do not have the political or financial capital to object with the impacts of their fossil fuel infrastructure. For example, the NAACP reported in Coal Blooded: Putting Profits before People that residents living within 3 miles of a coal plant were more likely to earn a below average annual income and be a person of color. Similar statistics have been recorded for natural gas infrastructure. Just like in Indiana, living next to such pollution hotspots has instigated widespread health effects like asthma and cancer, hitting residents with high medical bills and more sick days. Discriminatory health care and inflexible work further spiral communities into hardship.

These utilities are in a moment of existential crisis with the rise of renewables, though. Every solar panel installed eats away at their centralized, fossil fuel production—sending utilities and their traditional business model into a proclaimed death spiral. From gas pipelines to coal power plants, their investments are turning into stranded assets. In an attempt to slow the transition they’ve thrown their weight behind campaigns to stymie the growing renewables sector.

In some ways it feels as if they’re doubling down on fossil fuels. The drop in natural gas prices has led many investor-owned utilities to continue to build infrastructure like pipelines, often through nefarious self-deals that their rate-payers have little to no say in. Yet, rate-payers’ electricity bills will rise for projects whose use must be obsolete soon to stay below 1.5 degrees warming.

Ironically, utilities justify their advocacy for fossil fuels as a strategy to ensure affordable rates. For instance, they argue that net-metering policies for renewables increase rates for low income residents, as grid maintenance costs are shifted onto those who don’t have rooftop solar. This analysis has been thoroughly debunked. First, it refuses to acknowledge the true costs of fossil fuels—from health effects to environmental damage. Second, it glazes over the subsidies that prop up fossil fuels and continue to make them cheap, but horrible investments.

Equitable Renewables through Public Power

Justifying fossil fuels for low income households is highly flawed and inadmissible, but it does pose an important question: Who is reaping the benefits of renewables right now? How do we ensure that we are creating a more equitable energy system, decided by and for its community members?

Eliminating fossil fuels from the energy mix is paramount to creating healthy communities and stemming climate change. Low income households have much to gain from the renewable transition in part because they often have disproportionately higher bills due to older and less energy efficient homes. Yet, they are more likely to rent and have lower credit scores, precluding them from many of the renewable installation incentives.

Energy democracy is a concept that was developed as a solution not only to solve climate change, but also to address these entrenched systemic inequities. It is a vision to restructure the energy future based on inclusive engagement, where genuine participation in democratic processes provides community control and renewable energy generates equitably distributed, local wealth. A combination of strategies have been deployed around the globe to work towards energy democracy.

One such strategy is making utilities public entities in a hope to democratize the decision-making process and eliminate the overriding goal of profit maximization. This allows communities to more effectively demand moves away from fossil fuels and hold the utility accountable if it doesn’t. Fed up with investor-owned utilities’ inability to transition to equitable renewables, campaigns for public utilities are making huge strides in cities from Hamburg, Germany to Boulder, Colorado.

Publicly owned utilities are controlled by local government. Without the pressures of shareholder profit, they attempt to optimize benefits for their local customers who double as their owners and decision makers. Any profits they do make are given back to the local government: according to the American Public Power Association, public utilities pay 33% more back to the community they serve. There are already over 2,000 public power utilities in the United States and, although public power utilities tend to serve smaller constituencies, cities as large as Los Angeles rely on them for their electricity needs. The entire state of Nebraska is run on public power.

Hurdles to Public Power

That being said, the majority of public power utilities still rely predominantly on fossil fuels. Seventy three percent of their electric generating capacity comes from fossil fuels, slightly less than the 79% of investor-owned utilities. Much like investor-owned utilities, they also have investments in traditional fossil fuel infrastructure, making the transition a struggle. The difference here is that the community has a larger potential to shift energy provision. The question remains: is it being taken?

They are also not immune to rate scandals. City-owned Cleveland Public Power recently came under fire for their dubious charges on electricity bills. “Ecological adjustments” increased rates and were obscured on customer’s bills in order to take care of holes in the utility’s budget. Their actions, although unacceptable, were in some measure because they were feeling the heat from a private utility, FirstEnergy, vying for the same customer base.

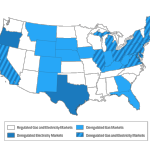

The ability for public power to provide energy democracy is in part determined by the policy landscape they operate within. In the case of Ohio, Cleveland Public Power was in direct competition with a private utility because the state has liberalized its grid. Liberalized electricity markets are deregulated to increase competition and allow customers choice in their electricity provider. It also means that electricity generation, transmission, and distribution are spliced into different markets. In other states, energy utilities are vertically-integrated, regulated monopolies. This means they own the majority of the operations associated with the electricity market and provide for all of the customers in a particular region. To date, there is little research that has been done on how these different contexts affect publicly owned utilities and their ability to foster energy democracy.

Investor-owned utilities have a hand in that important policy making; they wield significant political influence and state regulators repeatedly cater to their wants. For example, Dominion Power, an investor-owned utility, is one of the the largest forces in Virginian politics and has a serious agenda to continue the fossil fuel era.

Continued Research

There seems to be great opportunity in reclaiming power to the public sphere—with examples like Hamburg and Boulder on the cutting edge. Yet, this exploration begs the question: to what extent do these publicly owned utilities actually provide energy democracy? What struggles or constraints are they facing in doing so? And how does that contrast with investor-owned utilities?

Over the course of the next few months The Democracy Collaborative will be investigating these questions to identify how we enable robust system change that steers away from corporatized power towards energy democracy. This is part of a continuing series that will dive deeper into the grid to uncover best practices and political hurdles for public power.