Looking Back on October, 1917

First, stating the obvious: the October Revolution brought the working class to power in a major country, and the socialist state it designed transformed the country in fundamental ways, and lasted some 75 years. It broke new ground in human history, and the waves the revolution made touched every country in the world, to one degree or another.

Second, also obvious but not as well understood: the October Revolution failed in the end. People on the Left often argue about the date -- some set it near the death of Lenin, others with the ‘trials’ of the 1930s, still others with the death of Stalin and the rise of Khrushchev. Some in the 1960s target the Kosygin Reforms. Still others blame it on Gorbachev or Yeltsin. But what we know in the end, and as a result of the end, is that all the various outlooks had flaws. Lenin’s revolutionary period, Stalin’s various left and right turns, Trotsky’s left opposition, Bukharin’s right opposition, Khrushchev’s and Brezhnev’s muddling through, Gorbachev’s reforms — whatever can be said for their positive features and accomplishments, looking back from the vantage point of 100 years, they all came up short. And thus, they all failed.

Why? A lot has to do with the special features of Russia, plus the fact that the proletarian revolution there was the first in history to last more than a few months. They were in uncharted territory, and had to make up the only maps they had as they moved along.

The Russian Empire in 1917 covered one-sixth of the Earth’s land mass, and had a population of more than 170 million people. It was a ‘prison house’ of dozens of nationalities speaking nearly 100 languages and dialects, all subordinate to Russia and the Russian language. More than 80 percent of the population were peasants, with a substantial number of them being recently freed serfs. They were largely illiterate. Their government was an autocracy, ruled by one man, the Tsar, and a thin upper crust of nobility, about one percent. It was a brutal police state, and par- ties were largely illegal most of the time. Moreover, Russia came late to capitalism, with industrial workers numbering between 3 and 20 million, depending on how you counted them. Either way, they were a small minority. But the fact that the factories had come late also meant they were relatively advanced in their technol- ogy, and thus the workers in the larger ones were also relatively advanced in skills and literacy. Gaining power thus required the strategy of a worker-peasant alliance, with the workers being best positioned and most capa- ble of taking the lead.

Pre-war Russian peasant household

The Revolutions of 1917

All Russia’s inner conflicts were sharpened and spotlighted with its entry into World War I in 1914. The autocracy was brittle and stretched thin. The labor movement, though small, was militant. The peasants were hungry and restless, since they were the majority of the conscript army — and this in turn meant more mouths to feed, and fewer hands to bring in the crops. Russia’s situation was highly problematic. On one hand, socialist revolution seemed unlikely, due to the small size of the working class. On the other hand, Russia seemed the ‘weak link’ in the chain of capitalist empires. The war saw massive casualties, food shortages in the cities, and an increase in hunger and the desire for land in the countryside. The oppressed nationalities were restless, thinking of changing sides in the war. Russia was losing territory to Germany. In short, the country was in crisis.

Russian casualties in WW1

All the Russian socialists, and there were several varieties, thought the overthrow of the Tsar was in the cards. Other classes did too. In fact, one of the first to revolt was the Constitutional Democrats, the Cadets, a party made up largely of the youth of the nobility and the bourgeoisie. The workers of St. Petersburg had a trial run earlier, forming the Soviet of 1905, which was crushed. The Russian Social Democratic Labor Party led the workers and had two main factions: the majority (Bolsheviks) and the minority (Mensheviks). Lenin, as the leader of the Bolsheviks, had long trained his cadre and the more advanced workers, teaching why they had to fight not just for themselves, but for all subaltern classes and strata. They had to be ‘tribunes of the people’ and the vanguard of ‘consistent democracy’ in fighting the Tsar and any Tsarist collaborators. Unfortunately, Lenin was in exile in Switzerland for a considerable time.

Early in 1917, on International Women’s Day, a group of women workers held a demonstration in Petrograd demanding bread. The Tsar, as usual, ordered a harsh police and military repression, killing many, up to 1300. Only this time, one group of soldiers balked at the slaughter, and went over to the side of the women workers. Moreover, they went to other sections of the army in the city’s garrison and won them over, too. Once the army, largely peasants in uniform, turned against the Tsar, nearly all sections of the population joined the revolt. People stormed into the streets, and the large cities saw a sea of red flags. The Tsar abdicated in favor of his brother, but his brother quickly declined. The autocracy was over, at least in Petrograd, the capital at the time.

Period of Dual Power

But the ensuing situation was unique. In Petrograd and a few other major cities, there were two centers of power. On one hand, the most advanced workers, peasants and soldiers formed ‘soviets,’ the Russian word for councils, and were based in their factories or barracks. These local soviets federated into citywide soviets with elected delegates. Everyone else, but mainly the capitalists, formed a provisional revolutionary government, with all the parties of the old Duma represented. It basically constituted itself as a representative alliance between liberal reformers and socialists, save for some of the Bolsheviks. The soviets were deeply rooted among the masses, but without direct power. The provisional government held many levers of power, but with little grassroots base. At first the Bolsheviks were still a minority, even in the soviets, where the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (intellectual populists with a peasant base) held sway.

Now here is where things got really interesting. Nearly all the socialists in Europe, as well as Russia, thought the socialists should support, with various degrees of criticism, the Provisional Government, now headed by Alexander Kerensky, and enter it. They knew this would cede power to the bourgeoisie, which they thought could continue the job of building capitalism in Russia. They saw themselves as remaining a strong op- position bloc in the government, but slowly gaining strength and waiting for a more appropriate time to conquer a majority for socialism in the parliament. Capitalism then might be more suitably developed a decade or two down the road. This had been the orthodox view of the Second International. As for the new soviets, they could, in between, become a subordinate pressure group on the capitalist government.

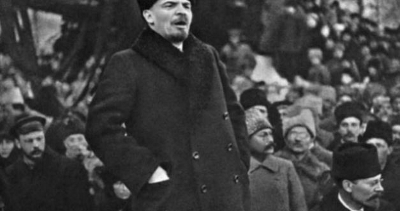

Lenin in April, arguing for a socialist revolution and an end to the war.

Lenin had an entirely different perspective, even a minority at first among the Bolshevik leading bodies. He arrived back in Russia, and immediately denounced any socialists supporting the Provisional Government. He also urged support for the slogan ‘All Power to the Soviets.’ In April, he declared for a proletarian and socialist revolution starting immediately. His comrades thought he had lost his senses and gone over to the anarchists. But Lenin had several keen insights. First was that the Russian bourgeoisie was too weak to rule democratically, and if all power went to the provisional government, it would soon become reactionary and, to use a latter-day term, fascist. Why? Because he saw, secondly, that the three key demands in February, ‘Bread, Peace and Land,’ had deeper implications. Lenin’s analysis was that the Kerensky government was comprised of die-hard ‘defencists’ and would continue the war until utter defeat and chaos. In short, it would not deliver peace, and because of this, it could not deliver bread and land either.

Lenin instead argued for ‘revolutionary defeatism,’ even at great cost in territory, partly with the hope it would inspire soldiers in other countries to revolt, and then revolutions might take place elsewhere, especially Germany, who would ally with the Russian revolution. In any case, he wanted a separate peace with Germany immediately. When this defeatism was argued for by him in the Bolshevik press, the other radical papers argued that Lenin was a German spy, and the charge aroused such anger among the masses that he had to go into hiding, mainly in

Finland. He still firmly and patiently argued that it was his way or utter disaster all around for everyone.

Revolutionary crisis has a way of accelerating time. What normally took a decade might take a year. What might take years took months, and months might take place in days. By July, the Bolsheviks were again gaining power in the soviets, while the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolu- tionaries were a leading bloc in the Kerensky government. The war deepened the crisis and its suffering. People cast aside the ‘spy’ slanders, and began to see Lenin’s great foresight. By July 17, the Bolsheviks organized a demonstration of 500,000 in Petrograd, and the Mensheviks in the government called for loyal troops to suppress it. Hundreds were shot down in the streets.

Lenin urged the workers in the soviets to organize factory-based armed ‘Red Guards’ in addition to the soldiers in their soviets loyal to the Bol- sheviks. He was preparing to arrest the government and seize all power for the soviets — but it took careful planning. First, he had to win a majority for the Bolsheviks in the soviets. This happened by the end of August. By October, Kerensky faced another crisis in the military. Taking advantage, the Bolsheviks and their Red Guards, together with the soldiers and now the sailors on arriving battleships in the harbor, assumed power, seizing all the key strong points of the police, transportation and communication facilities. They finally entered the Winter Palace and arrested the government ministers huddled there. All this took place, amazingly, with very little actual violence. All which had appeared solid melted into the air.

When the Soviets formed the new government, the Mensheviks and the right wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries walked out. The Bolsheviks and the Left Socialist Revolutionaries held the reins of power. (The main difference between Left and Right Socialist Revolutionaries was over whether or not to continue the war). So the new workers’ government, at first, was comprised of two parties. The events spread like a wave and soon took place in nearly every major Russian city. Only in the nation of Georgia did the Mensheviks hold power. (As Stalin’s youthful stomping grounds, this later held some irony.)

What did it all add up to at this point? It was a radical rupture in history. The Bolsheviks taking power and holding it sent shock waves around the world. Leftwing workers of all sorts in many countries celebrated the victory. And in a few, they hoped to repeat it as soon as they could. It also sent waves into the colonized world, also suffering from war and with hopes of national liberation. But despite the desire by many left par- ties to repeat it, it was also uniquely Russian. Workers might draw any number of lessons from it, but it was a hard act to follow. Most Western countries had no Tsar, no small groups of workers in a vast sea of illiterate peasants, no foreign imperialist army occupying large amounts of its territory, and by 1918, no bourgeoisie bent on continuing WWI. And as we have seen, each of these factors played a critical role that made a socialist seizure of power possible, even necessary, in Russia. Given the opening, Lenin thought it would be a high crime not to take it.

The Civil War

The initial seizure of power by the Bolsheviks was relatively easy compared to what soon followed. Taking power is one thing, defending it is quite another. Given the vast size of Russia, the Bolsheviks held power mainly in the large cities in Western Russia. Their reach was thin in the countryside, and practically non-existent in large areas to the east toward the Pacific Ocean. In the West, the German Army was still occupying much Russian territory. In November 1917 Lenin immediately set out to make peace, sending Leon Trotsky to negotiate with the Germans at Brest-Litovsk in Belarus. An armistice was signed by December 16, and a concluding treaty harsh to the Russians was signed on March 6, 1918. It might have been signed sooner had Lenin not again been in the minority in his Central Committee. His ‘left communists’ were against it, while Trotsky dilly-dallied under the slogan of ‘Neither War nor Peace.’ Both Lenin and unfolding events finally demonstrated that he was right. They had no material means to do anything other than sign.

Russia was finally out of one war, but another conflict was brewing, a civil war led by former Tsarist Generals, and in some cases, the Men- sheviks as well. Counter-revolutionary armies were forming in the South and the North, as well as in Eastern areas and the territories of Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland. The Red Guards and the Soldiers’ Soviets near Petrograd and Moscow were no match for these growing counter- revolutionary armies, also assisted by the West. The armed Bolsheviks might defend a few cities, but not much else.

The Bolsheviks needed a Red Army, and Lenin assigned the task to Trotsky. Here again, it became a revolutionary army entirely unique to Russia. The revolutionary workers and peasants involved in the soviets, who volunteered in sizable numbers, were still way too small and lacked leadership — making an insurrection was one thing, waged a protracted civil war against regular armies over vast territories was quite another. Trotsky used the materials at hand. First, many workers were required for war production, so he had to reach into the peasantry. Volunteering was not enough, so he had conscription passed. To get conscription observed, if persuasion failed, he held families as hostages, or simply shot a few potential recruits to make examples. Second, a few generals from the Tsarist Army had come over to the Bolsheviks for solid political or patriotic reasons. But Trotsky needed many more, and again took their families hostage to make them comply. By the end, more than 80 percent of the Red Army’s officers were former Tsarist officers. One way Trotsky made it work was to assign a reliable Bolshevik cadre as a ‘commissar’ to closely watch and report on each officer. Any funny business and the officer might be shot by the commissar.

Trotsky with one of his Red Army generals in the Civil War period.

Trotsky started forming the Red Army in January, 1918. But the ‘White’ Armies were winning battles throughout the year, gradually gaining territory. By June 1919, however, all Trotsky’s measures began to pay off; the Red Army began winning, and the Whites were in retreat. Final victory came in 1922.

At its peak, the Red Army had some 6.5 million troops. After demobilization and reorganization, the Red Army was maintained at just under 1 million. Could Trotsky have done things differently? Probably not. Despite later efforts to distort his role, he deserves a great deal of credit for saving the revolution in this period, and was given full praise by Lenin. (What happened later with Trotsky is another matter.)

The victory of the Red Army against the Whites was paired economically with what was called the ‘War Communism’ period (June 1918-March 1921). This meant that the army simply took whatever it needed from the peasants or shopkeepers at the point of a gun, both for the army’s own use and for shipment to the cities to feed the workers. It also meant a ban on strikes, strictly enforced food rationing, nationalization of nearly everything and forced labor projects. Nicolai Bukharin and a few others tried to raise this to a theory of an accelerated abolition of the market and private property, thus creating communism more quickly. But that ‘left’ theory flopped. People simply recognized it for what it was: survival in wartime at all costs, and to be rescinded as soon as possible.

The casualties and costs of the Civil War were enormous. Perhaps 200,000 Red Army dead and many more badly wounded. The toll on the Whites was even larger, and at the end, some two million pro-White Russians fled and emigrated abroad. The army casualties also included many of the most advanced Bolshevik workers of the soviets, severely affecting the political level and outlook of the party in the years following. To be sure, many youth rose up and joined to replace them, but the decades of experience of many well-trained working-class political cadres was largely gone. Moreover, famine raged in these years, plus typhus and many other diseases. By 1923, some 800,000 orphaned children were wandering the streets of Moscow alone. Other revolutionary upheavals in the future would face great hardships, such as China’s long march, the Nazi siege of Stalingrad or the Vietnamese wars of liberation. But none faced the unique circumstances here, or the unique solutions deployed. Much could be learned, but little copied.

In the midst of all this, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party changed its name to the Communist Party, and organized a new Third or Communist International, or Comintern. The founding congress was in 1919, with less than 60 delegates representing 34 parties. Grigori Zinoviev was put in charge. The Bolsheviks were trying to pull together those former member parties or party factions of the Second International that refused to support their own government in the war. Most all of those gathered, including Lenin, were still clinging to the hope that proletarian revolution would still sweep into Western Europe, or at least Germany, and then come to their aid with more powerful and plentiful productive forces and relief. It was more than hope, but a long held belief that this would come to pass. To some extent, it almost did.

There were short-lived ‘Soviet Republics’ in Bavaria and a few other cities in Germany. Bela Kun maintained a Soviet Republic in Hungary for several months. But these were crushed, and by 1923, in was clear to Lenin and others, if not everyone in the party, that the post-war insurgent wave was receding and not likely to come back soon. (At its peak in the 1930s, some 65 parties belonged to the Comintern, including both the Communist Party of China and the Kuomintang headed by Chiang Kai-shek). Lenin began looking more to the anti-colonial movements in the East as allies. But the notion of immediate aid from a socialist Europe died a painful death among those hoping for it most. It had been a major organizing principle for the Bolsheviks in the years leading up to 1917, but it was simply not in the cards that history dealt.

The New Economic Policy

The Civil War left Russia devastated. Economic life had nearly disappeared. Workers in cities were leaving for the country to scavenge for food. The peasants were already eating the bark off trees in some areas. There was next to nothing in the stores. Even as early as 1921, Lenin saw that War Communism was failing, and something drastic and new had to be done. He started with the ‘Tax in Kind,’ a new approach to getting what grain there was from the peasants to the cities. Prior to this, armed ‘War Communism’ groups simply went from one peasant household to another, seizing whatever grain or livestock they could find, leaving, at most, a bare minimum for the peasant to survive to the next harvest.

Small-town market operating under the NEP in 1925.

One byproduct, apart from hiding grain or even not planting it, was that too many peasants ate their livestock first, and only surrendered what was left. Naturally, all this wreaked havoc with the rural economy. So Lenin offered the peasant a new deal, a ‘tax in kind.’ The state would set a bare minimum of how many pounds of grain a peasant had to pay in tax, substantially lower than normal output. Anything left over, after family needs, the peasant could exchange with the state for manufactured goods. Naturally, for these goods, he would have to go through a local or regional middle man or distributor, like a farm implement and supply store. The new owners of these new exchanges took a profit, and were eventually called NEPmen.

Now any economist will note that this is a restoration, in a limited way, of market relations. The peasant is a small producer and the NEPmen are merchant capital. It meant getting the economy running in the countryside by restoring capitalism there. Lenin called it ‘state capitalism’ because it was still regulated by and subordinate to the worker’s state. He considered it a retreat from socialism, but a temporary one made necessary by dire circumstances. Truth be told, Marxists in these days had little idea of how to handle rural economies, since they usually thought in terms of countries like Germany, with large working classes and exchange within cities. Rural farming, they surmised, would somehow simply be industrialized. This is what the Bolsheviks initially thought, but soon found out the peasants had a variety of other ideas, some good, some not so good.

The ‘tax in kind’ immediately worked quite well, and grain moved into the cities and harvests went up. The tax was soon supplemented with other measures, allowing for foreign investment and setting up factories, and the use of foreign experts in Soviet factories. By 1924, the ‘tax in kind’ was changed to a simple cash payment, which encouraged even more peasant output. By this time, the government also implemented a strict monetary policy via the state-owned banks, and stabilized the ruble. This allowed much expansion of trade and manufacturing.

But the NEP undeniably was producing class stratification in the countryside -- rich peasants were getting richer, some middle peasants did well, others did not, as did the poor peasants. Some stayed poor, others moved up. And the NEPmen did best of all, including the urban NEPmen who worked as entrepreneurs. At some points the NEPmen were taxed heavily for getting ‘too rich’, but when it threatened to put them out of business, the taxes were relaxed.

Lenin and Bukharin were the main architects of the NEP. Many of the Bolsheviks, including both Stalin and Trotsky, were dubious, but had no ready alternative. Lenin died in 1924, leaving the policy and its implementation to Bukharin. By 1928, Stalin put an end to the NEP, and set the stage for his newly conceived alternative, the first ‘Five Year Plan’ which included a radical new approach to the countryside.

The Rise of Stalin

Libraries can be filled with books about Stalin, so this short account is bound to find objections. We’ll try anyway. The first thing that needs to be said is that he began as a revolutionary youth from Georgia, and soon became a Bolshevik. He impressed Lenin early on for two reasons. First, Lenin liked Stalin’s attempt at theoretical work, especially on documents that led to his classic booklet, ‘Marxism and the National Question.’ Lenin approved the work. Second, Lenin liked Stalin’s sense of self-discipline. After giving him a few difficult assignments, he concluded that Stalin was a fighter and a party member who would diligently carry out any task assigned to him, and usually well. Thus, Lenin drew him into the Central Committee and his inner circle. The next thing to be said is that Stalin wisely cast himself as Lenin’s pupil, and not as a ‘co-leader of the revolution,’ as Trotsky did at times. This put him in a good light with other Bolsheviks at the top, and even more so with the lower circles.

Stalin was also very adept at understanding how party-building was, in large part, the building of relationships, and building them far and wide. This meant he not only built the party, he also built his own circles of friends within the party, also far and wide. Stalin had done well on sev- eral fronts in the Civil War, and he was also good as a publicist, writing for and editing Pravda and other publications. He headed up work on the nationalities commission. So, in 1922, Lenin proposed him as general secretary for the Central Committee. Since Stalin was considered among the top five or six leaders in the party, this came as no surprise, and he was accepted to the post. Stalin was not a very good orator, but when he did speak, he had a manner of making complicated things clear, step by step, to those alongside or below him. He was known for speaking very little initially in debates in CC meetings. But at a critical point, he was known for taking, as the Quakers call it, ‘the sense of the meeting,’ i.e., summing up in brief, concise terms what a solid majority would find agreeable. When Lenin died, most of the party saw no problem with him being at the center of the new leadership. He accepted the job.

Stalin was also an ideologue, but willing to bend pragmatically at a few critical points. He read voraciously, trying to make up for his limited seminary training, in view of the university backgrounds of others on top. He studied Marxism as if it were a science on a par with theoretical physics. With it, he believed he could find a good answer to nearly every problem. When Lenin was ill, but experimenting with the NEP along with Bukharin, Stalin was dubious of innovations that involved capitalism, but held his tongue. He was still trying to work out what he thought Marxism demanded on the matter. He sensed he knew more about the peasant life in remote areas, certainly more so than many of his more urbane comrades. He was once noted as saying that while a few peasants were communists, the vast majority, even after the revolution, were still tsarists in their minds, by habit, even without their Tsar. They wanted one leader, and a strong one, who would make clear whatever was expected of them, and still might, at times, show mercy.

Cutting a Path While Moving ‘Ahead’

Stalin, like most Bolsheviks, saw Russia as a country with urban islands of socialism engulfed by a vast sea of capitalism in the countryside, and if that capitalism grew too strong, they would not be able to control it. Truth be told, Marxism really had no ‘correct line’ on how to deal with the matter, since it had really never faced it before. Stalin had to make one up with the tools at hand, so he decided it was the revolution’s next task to overthrow capitalism in the countryside, beginning with the richest farmers — these were people with a small herd of cattle, and a bit more land than most, so he might have to hire five or ten hands to help with the harvest. These were the ‘kulaks’ and Stalin set out to expropriate them, expel them to Siberia or put them to work as farmhands, i.e., to ‘liquidate them as a class.’ But it didn’t stop with the kulaks. Stalin’s aim was to industrialize all of agriculture in a variety of large state farms and cooperatives. Peasants in general would be ‘proletarianized’ into rural industrial workers.

The process was started in 1928, as part of the Five Year Plan. If the process was viewed as something to happen gradually, over decades, with step-by-step mechanization, it might have made some sense. But the workers in the cities didn’t have enough to eat, and Stalin was set on a vast growth of industry there as well. He noted that unlike the West, Russia had no colonies to exploit to fund their growth, so it would be squeezed out of the peasants, and it would be done quickly. He wanted to catch up to the West in ten years.

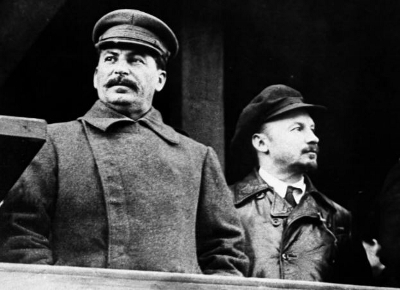

Stalin with Bukharin

Thus, Stalin launched what became a second civil war, reorganizing and transforming the countryside at the point of a gun. There were enormous casualties, but Stalin didn’t flinch. In his mind, and in that of most of the party, they were crushing class enemies, and one should not vacillate. In ten or so years, he reached his goal, and it is often said the Soviet agriculture has still not recovered to this day. Collective farming rarely reached the productivity of say, middle peasants cooperatively organized. The rural ecology suffered as well, with destructive dust storms similar to those due to poor farming methods in the US Midwest. But it did get him his new steel mills and machine works.

Stalin’s ‘left’ armed collectivization in this period was also paired with a ‘left’ turn in the Comintern. Stalin, acting as ‘centrist,’ had first built a right-center alliance in the Soviet party to expel Trotsky and the ‘left’ opposition. Then he formed a left-center alliance to expel Rykov, Bukharin and the ‘right’ opposition by 1930. The party was now united under ‘Marxism-Leninism’ as defined by Stalin, with no open opposition blocs. Since Stalin had nurtured his own relationships within the party, especially in the police and intelligence agencies, it was now fully controlled top-down by the Politburo, and he rarely was opposed in that body. Having gradually co-opted many old forms of rule and even the personnel, Stalin was also finally able to give most of the still ‘tsarist-thinking’ rural Russians the secular strong one-man leader he believed they had been hoping would arrive. It also meant the Soviet party called the shots with all the other parties in the Comintern, or at least it tried to do so. Stalin developed what was called the ‘third period’ ultraleft line that held forth from the 1928 Sixth Comintern Congress to about 1935. It was most notorious for imposing a view that rising fascism and social democracy were ‘twins’ and both had to be fought together, with the social democrats often being more dangerous.

It’s hard for leftists today, with their hindsight, to understand where this ‘social fascist’ viewpoint came from. One needs to note, however, that the Bolsheviks, in their Civil War, fought several separate White Armies concurrently. Some were led by Tsarist reactionaries, but at least one had Mensheviks in the leadership. So, on the battlefield, there was little difference. Plus earlier, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, key Bolshevik allies in Poland and Germany, were assassinated by police under a right social democratic government. It still doesn’t justify the failure of German Communists and Social Democrats to form a common front against Hitler. (The ‘third period’ Comintern argued for a ‘united front from below,’ meaning they would fight with the rank-and-file members of these organizations, but oppose their leaders at the same time. It largely failed as a policy.)....(read continuation here.)

Putin in his KGB days

By 1988, the wall came down in Berlin. Communist parties in power collapsed or were replaced in what seemed like a blink of an eye. The new gangster capitalists took charge in Russia, the USSR dissolved, and the Cold War was over.

So even if various flavors of leftist groups and theorists might still argue about the date, the vast project initiated by the October Revolution was definitively over and capitalists reigned once more in Russia, and as Stalin had envisioned, it had one strong leader at the top. Some might still argue that this was all the result of external players and forces, and if left alone, the USSR might still be hanging on or even thriving. There is one powerful argument against this. Hardly any workers anywhere in Russia put up much resistance to the overthrow of a party and state that was supposedly their own. To understand why, we have to look back to the 1930s. The Five Year Plans developed a command economy and supposedly eliminated nearly all markets. But every worker knew it wasn’t true. There were ‘tiered’ markets for the upper crust ‘nomenclatura’ or party elites. And there were the black markets for everyone else, to make do as they might. This spread cynicism.

Next were the purge trials and the gulags that continued long after them. It meant that if you were a careerist, you still might risk joining the party as a way to maneuver to a comfortable life, but you had to play the game carefully, and democracy was a third rail you didn’t want to touch. This created a working class that retreated into private life, and it became passive so far as politics was concerned. It simply wasn’t worth the risk. The result was a depoliticized working class, the very opposite of Lenin’s dreams of the early workers he discussed in ‘What Is to Be Done.’ If the elites were changing at the top, too many workers thought it might mean things got worse or better, but in any case, of little concern to them.

This will probably change someday. A Communist Party of Russia still exists, a minority party in a largely rubber-stamp parliament. Strikes and street demonstrations break out around a variety of democratic issues. And one with optimism of the will has to think that a smoldering core of revolutionary workers in Russia will have an important advantage. If they study their history well, they will find many powerful lessons in both what to do and what NOT to do going forward.

[Carl Davidson is a national committee member of CCDS, a LeftRoots Compa and a DSA member. He lives in Western PA, where he also works as a member of USW Local 3657, the 12th CD PDA and manages the Online University of the Left.]

This article is a summary of a longer article (http://ouleft.org/wp-content/uploads/carld-october-1.pdf) that appeared in the anthology, "The Russian Revolution & the Soviet Union: Seeds of 21st Century Socialism," published by CCDS at a Changemaker Publications at Lulu.com.]