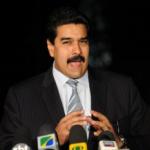

Trump Doubles Down on Sanctions and Regime Change for Venezuela

On November 3rd President Maduro of Venezuela proposed a meeting with creditors, for November 13th in Caracas, to discuss a restructuring of Venezuelan public debt. On November 8th, the Trump administration reacted by warning US bondholders that attending this meeting could put them in violation of US economic sanctions against Venezuela. Such a violation can be penalized by 30 years in prison and up to $10 million dollars in fines for businesses.

Then on Thursday, the administration added ten more Venezuelan officials to the list of people under US sanctions. The new targets included electoral officials and also the head of the government’s main food distribution program.

The sanctions violate the charter of the Organization of American States (Chapter 4, Article 19) and other international treaties that the U.S. has signed.

It is important to understand both the context and the intended (as well as likely) effects of the Trump administration's’ actions. With encouragement from Florida Senator Marco Rubio and other Republicans, Trump has been trying to help topple the elected government of Venezuela. After four months of violent street protests failed to accomplish this goal (and also alienated much of the Venezuelan population), most of the Venezuelan opposition opted to participate in the gubernatorial elections of October 15th.

The leading and most reliable pro-opposition pollster, Datanálisis, forecast an overwhelming opposition victory, with 18 governors. The result, however was the opposite: the governing PSUV (Socialist) party won 18 of the 23 races.

Although there appear to be false vote totals that swung one close governor’s race (in Bolivar state) -- and this should be investigated -- the other results are not in question and were accepted by most of the opposition. There are various explanations for the surprise result, but the most credible and important appear to revolve around opposition voter abstention and higher than expected turnout of pro-government voters. Improved food distribution probably helped the government.

One thing that seems to have hurt the opposition was their support for the Trump sanctions. According to Datanálisis, Venezuelans were against the sanctions by a margin of 61.4 to 28.5 percent; and among the unaligned voters, more than 70 percent were opposed. Also, 69 percent wanted the opposition and government to re-initiate talks. The regime change strategy had failed.

But the Trump administration decided to double down on both regime change and sanctions. The strategy appears to be to prevent an economic recovery and worsen the shortages (which include essential medicines and food) so that Venezuelans will get back in the streets and overthrow the government.

The Trump sanctions explicitly prohibit new borrowing. This is to ensure that Venezuela cannot do what most governments do with most of their debt, i.e. “roll over” the principal by borrowing anew to pay the principal when a bond matures. For example, last week the government had to scramble to pay off $1.2 billion in principal for PDVSA bonds, to avoid default. (Although Venezuela cannot borrow on international markets right now, they could possibly do so in the foreseeable future).

The sanctions also make a debt restructuring much more difficult or impossible. In a debt restructuring, interest and principal payments are postponed into the future, and the creditors receive new bonds – which the sanctions explicitly prohibit. Now the Trump administration is also threatening even the negotiations for a restructuring, under the pretext that the chief negotiators Vice President Tareck El Aissami and Economy Minister Simon Zerpa, have been sanctioned for alleged drug trafficking and corruption, respectively. The Trump administration has not presented any evidence for these allegations.

The US Treasury statement of November 9 justifies targeting election officials because of “numerous irregularities that strongly suggest fraud helped the ruling party unexpectedly win a majority of governorships.” This is a fabrication, and is reminiscent of the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election, when Washington was the last government to recognize the result. In that race, a statistical analysis of the election-day audit showed that the odds of getting the official result, if the true result was an opposition victory, were less than one in 25,000 trillion.

But this is what regime change efforts are all about: de-legitimation – if the election results don’t concur, they must be declared fraudulent – and economic strangulation.

Of course, the Venezuelan government will have to make some serious economic reforms – most importantly, the unification of the exchange rate and other measures to bring down an inflation rate that is passing 1000 percent annually – if there is to be an economic recovery. But the price of oil has risen 33 percent from a low point in June, and despite declining oil production, Venezuela’s exports are up 28 percent from last year (first eight months, estimate from Torino Capital).

Trump and his allies in the EU and the right-wing governments in Argentina and Brazil, as well as the fanatical Secretary General of the OAS, want to make sure that a recovery never happens. And despite all their blather about human rights and democracy, it is not a peaceful strategy they are promoting as they take measures to increase Venezuelans’ suffering in the hopes of provoking the overthrow of the government. This is not “democracy promotion.” It is regime change, by any means necessary – as Trump, in his usual blustery way, made clear when he threatened military action against Venezuela.

[Mark Weisbrot is co-director and co-founder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. He is co-author, with Dean Baker, of "Social Security: The Phony Crisis" (University of Chicago Press, 2000), and has written numerous research papers on economic policy. He is also president of Just Foreign Policy.]

This article was made possible by the readers and supporters of AlterNet.