Upton Sinclair is Dead and the Food Industry has the Trump Admin. Right Where It Wants It

When Donald Trump was elected president, American consumer protection groups, food safety advocates and commentators were “on high alert.” Two months prior, his campaign had posted—and later deleted—an online fact sheet that highlighted a number of “regulations to be eliminated” under his proposed economic plan.

The document read in part:

The FDA Food Police, which dictate how the federal government expects farmers to produce fruits and vegetables and even dictates the nutritional content of dog food. The rules govern the soil farmers use, farm and food production hygiene, food packaging, food temperatures and even what animals may roam which fields and when. It also greatly increased inspections of food ‘facilities,’ and levies new taxes to pay for this inspection overkill.

Now, with Trump’s first year in office characterized by tumult and scandal (including the FBI’s ongoing Russia probe, his response to white supremacist violence in Charlottesville and his continuous goading of North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, etc.) it is understandable that concerns about America’s food supply have been sidelined. To paraphrase food writer Mark Bittman, how relevant are food issues when the need to defend basic democracy is far greater?

As it turns out, very—the two have been inextricably linked since the emergence of the modern food industry at the turn of the 20th century. Then, as now, lax regulatory legislation combined with rampant consumer fear has allowed corporate interests to redirect conversations about food safety and position themselves as the best solution to the problem.

In the months after November 2016, Bittman reconsidered his position, telling New York magazine in June that “good food can define a democracy.” He's right—food issues profoundly affect everyone across class, gender, racial, and political lines—and it is time to give them the attention they deserve. In an era when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are increasingly compromised, and workers in the American food industry are often poorly paid and under-protected, advocates and commentators must consciously work to dismantle the elitism that so often surrounds cultural discussions about food in the United States.

In short, it is no longer enough to Instagram the latest trendy food items or extoll the supposed virtues of “clean eating.” In Bittman’s words, “to be a foodie now is to know that we must protect the rights of farm workers, retail workers, restaurant workers, immigrants, anyone who is harassed at work and/or at home (mostly women), and laborers who make minimum wage or less, often without benefits.” Moreover, it is imperative “to address [diet, environmental, and farming issues] in the context of making sure all people can afford good food, as well as in the contexts of public health, general well-being, and the means to care for the earth.”

These are not unfounded concerns. The rise of neoliberalism in the United States has led to the continued deregulation of the food industry and allowed cozy relationships between policymakers and Big Ag and Big Food lobbyists to flourish. The Bush-era and early Obama years were, in the words of Vice reporter Tom Perkins, particularly “dark days for food safety,” with alarmingly regular product recalls and outbreaks of often-deadly foodborne illnesses. Consider, the 2009 salmonella outbreak in a Georgia peanut butter factory that sickened 22,500 people and killed nine, and the 2006 outbreak of E. coli, linked to tainted spinach grown in fields near a large cattle ranch in California.

Although the Obama administration updated America’s food safety laws for the first time since the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938, the bipartisan Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), when it passed in 2011, was just a modicum of progress. The FSMA allowed the FDA to increase inspections and oversee farming practices. It also allowed them to expand their power to recall tainted foods and demand accountability from food companies in matters such as accurate labeling. However, in spite of these seemingly tougher measures, President Obama and Congress failed to provide the FDA with the necessary funding to adequately enforce its regulations.

Given this context, it is no wonder that for the last decade or so, major American food manufacturers have consistently used advertising and marketing campaigns to try and subvert the scrutiny they’ve come under. Buzzwords like “authentic,” “natural,” “small batch,” and “artisanal” abound in product advertisements (for everything from fast-food breakfast sandwiches to tortilla chips) to emphasize their apparent wholesomeness at a time when such qualities are in short supply.

Some historians and commentators have traced these issues to the 1980s with the rise of Reagan-era “E. coli conservatism,” in which “government shrinks and shrinks until people get sick,” however they have much deeper roots. Concerns that surround the food we eat—a concern reflected in advertising campaigns—are the latest episode in a battle that has been ongoing since the late 19th century.

The food industry's rise and tactics

With the advent of branded, mass-produced food items at the turn of the 20th century, American consumers became wary about purchasing food produced under conditions they could not see first-hand. At the same time, the advertising industry as we know it today was born, and it worked tirelessly to create a demand for these new products. It also helped minimize fears about them.

As Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle portrays, consumers had valid reasons to worry about the content and quality of the food they ate and the conditions under which it was produced. In response, a grassroots consumer movement—driven by organizations led by middle class women, religious organizations, public health officials, physicians, journalists and politicians—lobbied for the passage of federal regulatory legislation, and their quest was ultimately successful when the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906.

A short recap of the Progressive Era and the cultural response to Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel, The Jungle. (Video: Vision Chasers / YouTube)

A closer look at how the fight for pure food was co-opted by big business reveals a more complex story than the popular perception that assumes the Pure Food and Drug Act was a landmark victory for consumer protection in the United States and a triumph of the Progressive Era. In a similar manner to today, food manufacturers at the turn of the 20th century were keenly aware of what their critics were saying, and they used advertising and marketing to destabilize these critiques.

Echoing the dictates of credible activists and food gurus like National Consumers’ League co-founder Alice Lakey and Boston Cooking School teacher and cookbook writer Maria Parloa, companies like Heinz promulgated the idea that American consumers had responsibilities at an individual level to become informed shoppers and learn about how their food was produced.

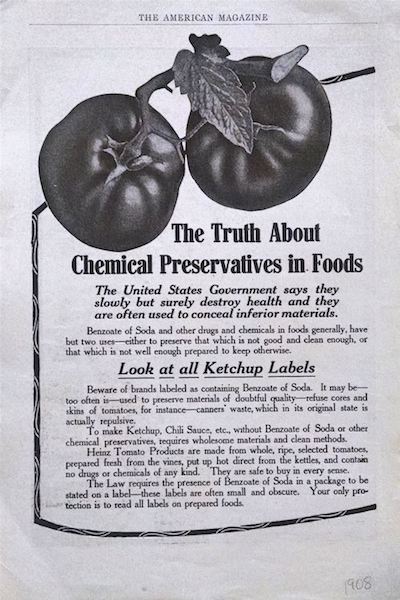

One Heinz advertisement pointedly asked consumers, “What Is In The Food You Eat?” With text focused on the perceived dangers of benzoate of soda (a preservative not prohibited under federal law but considered by some to be dangerous to human health), this advertisement notes that this substance was used in part “to make food acceptable to the eye, which, if you knew how and of what it was made, you would not eat under any circumstances.” It also links their products to homemade goods “cooked exacting with care,” and in bold letters, implores consumers to “Look at the Label” before making any purchases.

A Heinz advertisement from 1908. (Image: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

This ad, part of a campaign devised by Philadelphia-based advertising agency N.W. Ayer & Son in the early 20th century, is an example of what Canadian academic and journalist Andrew Potter describes as “conspicuous authenticity.” If, as he writes in Maclean’s, “authentic social relations are built around small, organic communities that are nonhierarchal, noncommercial, and nonexploitative,” advertisements like these can be read as a calculated attempt to craft a discourse around food products based on notions of ‘goodness’ and ‘honesty.’ ”

The American food industry also turned its eye inward as a way of reassuring consumers, especially amidst the confusion that followed the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act when it seemed unclear how and to what degree this new legislation would be enforced. Philadelphia newspaper the North American reported in 1910 that “health and food departments of many states have utterly cast aside the federal laws as virtually worthless” in favor of enforcing “their far better state laws.”

Another wholesome Heinz ad. (Image: Pintrest)

In a way that uncannily mirrors our present moment, the paper also noted that more pressing political concerns like the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act and the conservation of water power, timber and coal had largely pushed food issues out of the American public’s mind. As a result, food manufacturers began to position themselves as the only hope for winning the flagging fight for pure food, and they were met with surprisingly little criticism or opposition.

A 1910 issue of the National Food Magazine reprinted an editorial from the North American declaring that the “biggest and best known manufacturers are now among the leaders of the pure food war.” In the same year at the convention of the National Canners’ Association in New Jersey, one member put forth a proposition to levy a $1,000 fine for every canning company that transgressed the rules for ensuring purity—rules, it is important to note, that seemed to come from the association itself rather than from federal law.

As the North American reported, amidst cheers of approval from attendees, C.C. Winningham of Chicago “advocated a special pure food label guaranteed by the association, which is to be collector of the heavy fine in case of violation of its rules.” Similarly, a group of approximately 20 large food companies—including Heinz, the Shredded Wheat Company and the Franco-American Food Company— formed the American Association for the Promotion of Purity in Food Products in order to elevate “the standards of the food producing interests of this country.”

This organization—and its boosters in the press—would have had consumers believe that its members were part of a “certain class of manufacturers whose natural sense of honor” forbade them from breaking federal or state pure food laws. As the National Food Magazine explained, the association fought “ardently with the public” for the passage of the 1906 Act, and “fought with all their strength” to save it in the years that followed. Because of this, the publication argued, every consumer in the United States owed “a lasting debt of gratitude” to these manufacturers, some of whom used advertising as a way to boast of their membership in the association.

Moving backwards

By appointing itself as a key champion of federal pure food legislation when the cause was faltering—with both tacit and explicit approval from the press—big business was able to appropriate the cultural discussions surrounding food in the United States at the turn of the 20th century in a way that boosted their bottom lines rather than consumer protection. In doing so, it also laid the groundwork for our current moment. These tactics pioneered by corporate interests show no sign of abating, which makes this moment in U.S. history particularly significant when considering the fears and uncertainties that continue to surround the production and consumption of food in the United States.

With the Trump administration seemingly “ready to drag the nation back” to the years before the FSMA, it is more important than ever to be critical of the emphasis food companies have long placed on individual consumer responsibility and questionable self-regulation strategies communicated via marketing and advertising.

(Image: azquotes.com)

________________________________________________

Alana Toulin is a Ph.D. candidate in U.S. history at Northwestern University. Her dissertation, "Open Tables: Restaurant and Reform in Progressive Chicago," considers how Chicagoans from across class, gender, and ethnic and racial lines experienced and shaped their city’s public dining culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Reprinted with permission from In These Times. All rights reserved. Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate. Never has independent journalism mattered more. Help hold power to account: Subscribe to In These Times magazine, or make a tax-deductible donation to fund this reporting.