Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: 'Trump is Where He is Because of His Appeal to Racism'

“Like all people my age I find the passage of time so startling,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar says with a quiet smile. The 70-year-old remains the highest points-scorer in the history of the NBA and, having won six championships and been picked for a record 19 All-Star Games, he is often compared with Michael Jordan when the greatest basketball players of all time are listed. Yet no one in American sport today can match Kareem’s political and cultural impact over 50 years.

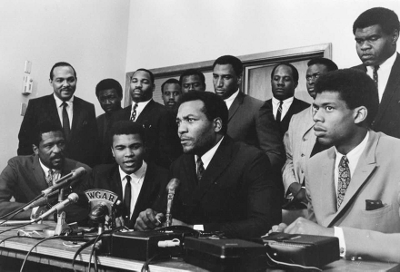

In the 90 minutes since he knocked on my hotel room door in Los Angeles, Abdul-Jabbar has recounted a dizzying personal history which stretches from conducting his first-ever interview with Martin Luther King in Harlem, when he was just 17, to receiving a hand-written insult from Donald Trump in 2015. We move from Colin Kaepernick calling him last week to the moment when, aged 20, Kareem was the youngest man invited to the Cleveland Summit – as the leading black athletes in 1967 gathered to meet Muhammad Ali to decide whether they would support him after he had been stripped of his world title and banned from boxing for rejecting the draft during the Vietnam War.

Kaepernick, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback who has been shut out of the NFL for his refusal to stand for the US national anthem, is engaged in a different struggle. But, after being banished unofficially from football for going down on a bended knee in protest against racism and police brutality, Kaepernick has one of his staunchest allies in Abdul-Jabbar.

At the Cleveland Summit Abdul-Jabbar was called Lew Alcindor, for he had not converted to Islam then, and he became one of Ali’s ardent supporters. When Ali convinced his fellow athletes he was right to stand against the US government, the young basketball star knew he needed to make his more reticent voice heard. He has stayed true to that conviction ever since.

“We’re talking about 50 years since the Cleveland Summit, wow,” Abdul-Jabbar exclaims. “We were tense about what we were going to do and Ali was the opposite. He said: ‘We’ve got to fight this in court and I’m going to start a speaking tour.’ Ali had figured out what he had to do in order to make the dollars – while fighting the case was essential to his identity. Bill Russell [the great Boston Celtics player] said: ‘I’ve got no concerns about Ali. It’s the rest of us I’m worried about.’ Ali had such conviction but he was cracking jokes and asking us if we were going to be as dumb as Wilt Chamberlain [another basketball great who played for the Philadelphia 76ers]. Wilt wanted to box Ali. Oh my God.”

Some of the things we fought against then are still happening. Each generation faces these same old problems

-Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Abdul-Jabbar’s face creases with laughter before he becomes more serious again. “Black Americans wanted to protect Ali because he spoke for us when we had no voice. When he said: ‘Ain’t no Viet Cong ever called me the N-word’, we figured that one out real quick. Ali was a winner and people supported him because of his class as a human being. But some of the things we fought against then are still happening. Each generation faces these same old problems.”

The previous evening, when I had sat next to Abdul-Jabbar at the Los Angeles Press Club awards, the past echoed again. Abdul-Jabbar received two prizes – the Legend Award and Columnist of the Year for his work in the Hollywood Reporter. Other award winners included Tippi Hedren, who starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller, The Birds, and the New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey who broke the Harvey Weinstein story two months ago. As if to prove that the past can be played over and over again in a contemporary loop, we saw footage of Hedren saying how she would not accept the sexual bullying of Hitchcock in the 1960s just before Kantor and Twohey described how they earned the trust of women who had been abused by Weinstein.

Abdul-Jabbar explained quietly to me how much of an ordeal he found such occasions. He was happiest talking about John Coltrane or Sherlock Holmes, James Baldwin or Bruce Lee, but people kept coming over to ask for a selfie or a book to be signed while, all evening, comic references were made to his height. Abdul-Jabbar is 7ft 2in and he looked two feet taller than Hedren on the red carpet.

The following morning, as he stretches out his long legs, I tell Kareem how I winced each time another wise-crack was made about his height. “I can tell you I was six-foot-two, aged 12, when the questions started,” Abdul-Jabbar says. “‘How’s the weather up there?’ I should write down all the things people said when affected by my height. One of the funniest was at an airport and this little boy of five looked at my feet in amazement. I said: ‘Hey, how you’re doing?’ He just said: ‘You must be very old – because you’ve got very big shoes.’ For him the older you were, the bigger your shoes. That’s the best I’ve heard.”

In his simple but often beautiful and profound new book, Becoming Kareem, Abdul-Jabbar writes poignantly: “My skin made me a symbol, my height made me a target.”

Wooden was mortified when a little old lady stared up at the teenage Kareem and said: “I’ve never seen a nigger that tall.” Even though he would later say that he learnt more about man’s inhumanity to man by witnessing all his protégé endured over the years, Wooden’s memory of that encounter softened the woman’s racial insult by saying that she had called Kareem “a big black freak.”

Abdul-Jabbar nods. “He would never see a little grey-haired lady using such language. When it doesn’t affect your life it’s hard for you to see. Men don’t understand what attractive women go through. We don’t get on a bus and have somebody squeeze our breast. We have no idea how bad it can be. For people to understand your predicament you’ve got to figure out how to convey that reality. It takes time.”

Abdul-Jabbar made his first high-profile statement against the predicament of all African Americans when, in 1968, he boycotted the Olympic Games in Mexico. After race riots in Newark and Detroit, and the assassination of King in April 1968, he knew he could not represent his country. “Dr Harry Edwards [the civil rights activist] helped me realise how much power I had. The Olympics are a great event but what happened overwhelmed any patriotism. I had to make a stand. I wanted the country to live up to the words of the founding fathers – and make sure they applied to people of colour and to women. I was trying to hold America to that standard.”

The athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos took another path of protest. They competed in the Olympic 200m in Mexico and, after they had won gold and bronze, raised their gloved fists in a black power salute on the podium. “I was glad somebody with some political consciousness had gone to Mexico,” Abdul-Jabbar says, “so I was very supportive of them.”

Does Kaepernick’s situation mirror those same issues? “Yeah. The whole issue of equal treatment under the law is still being worked out here because for so long our political and legal culture has denied black Americans equal treatment. But I was surprised Kaepernick had that awareness. It made me think: ‘I wonder how many other NFL athletes are also aware?’ From there it has bloomed. This generation has a very good idea on how to confront racism. I talked to Colin a couple of days ago on the phone and I’m really proud of him. He’s filed an issue with the Players Association about the owners colluding to keep him from working. That’s the best legal approach to it. I hope he prevails.”

Over dinner the night before, he intimated that Kaepernick knew he would never play in the NFL again. “We didn’t get that deep into it,” he says now, “but he has an idea that is what’s going down. But he’s moved on. He hadn’t prepared for this but he coped with different twists and turns. Some of the owners in the NFL are sympathetic, some aren’t. It’s gone back and forth. But he appreciates the fact that kids in high school have taken an interest. So he got something done and this generation’s athletes are now more aware of civil rights.”

Kaepernick has been voted GQ’s Citizen of the Year, the runner-up in Time magazine’s Person of the Year and this week he received Sports Illustrated’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award. Considering the way Kaepernick “has never wavered in his commitment”, Abdul-Jabbar writes in Sports Illustrated that: “I have never been prouder to be an American … On November 30, it was reported that 40 NFL players and league officials had reached an agreement for the league to provide approximately $90m between now and 2023 for activism endeavors important to African American communities. Clearly, this is the result of Colin’s one-knee revolution and of the many players and coaches he inspired to join him. That is some serious impact … Were my old friend still alive, I know he would be proud that Colin is continuing this tradition of being a selfless warrior for social justice.”

In my hotel room, Abdul-Jabbar is more specific in linking tragedy and a deepening social conscience. “I don’t know how anybody could not be moved by some of the things we’ve seen. Remember the footage of Tamir Rice getting killed [in Cleveland [in 2014]. The car stops and the cop stands up and executes Tamir Rice. It took two seconds. It’s so unbelievably brutal you have to do something about it.

“LeBron James and other guys in the NBA all had something to say about such crimes [James and leading players wore I Can’t Breathe T-shirts in December 2014 to protest against the police killing of Eric Garner, another black man]. They weren’t talking as athletes. They were talking as parents because that could have been their kid.”

If the NFL appears to have actively ended Kaepernick’s career, what does Abdul-Jabbar feel about the NBA’s politics? “The NBA has been wonderful. I came into the NBA and went to Milwaukee [where he won his first championship before winning five more with the LA Lakers]. Milwaukee had the first black general manager in professional sports [Wayne Embry in 1972]. And the NBA’s outreach for coaches, general managers and women has been exemplary. The NBA has been on the edge of change. I was hoping the NFL might do the same because some of the owners were taking the knee. But they’re making an example of Colin. It’s not right. Let him go out there and succeed or fail on the field like any other great athlete.”

Abdul-Jabbar smiles shyly when I ask him about his first interview – with Martin Luther King 53 years ago. “As a journalist I started out interviewing Dr King. Whoa! By that point , Dr King was a serious icon and I was thrilled he gave me a really good earnest answer. Moments like that affect your life. But my first real experience of being drawn into the civil rights movement came when I read James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.”

Has he seen I Am Not Your Negro – Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary of Baldwin? “It’s wonderful. I saw it two weeks after the Trump election. It was medicine for my soul. It made me think of how bad things were for James Baldwin. But remember him speaking at Cambridge and the reception he got? Oh man, amazing! I kept telling people: ‘Trump is an asshole but go and see this film. Trump doesn’t matter because we’ve got work to do.’”

In 2015, after Abdul-Jabbar wrote an opinion piece in the Washington Post, condemning Trump’s attempts to bully the press, the future president sent him a scrawled note: “Kareem – now I know why the press always treated you so badly. They couldn’t stand you. The fact is you don’t have a clue about life and what has to be done to make America great again.”

Abdul-Jabbar smiles when I say that schoolyard taunt is a long way from the oratory of King or Malcolm X. “If you judge yourself by your enemies I’m doing great. Trump’s not going to change. He knows he is where he is because of his appeal to racism and xenophobia. The people that want to divide the country are in his camp. They want to go back to the 18th century.

“Trump wants to move us back to 1952 but he’s not Eisenhower – who was the type of Republican that cared about the whole nation. Even George Bush Sr and George W Bush’s idea of fellow citizens did not exclude people of colour. George W’s cabinet looked like America. It had Condoleezza Rice and the Mexican American gentleman who was the attorney general [Alberto Gonzales] and Colin Powell. Women had important positions in his administration. Even though I did not like his policies, he wasn’t exclusionary.

“Look what’s going on with Trump in Alabama [where the president supports Roy Moore in the state senate election despite his favoured candidate being accused of multiple sexual assaults of under-age girls]. You have a guy like him but he’s going to vote the way you want politically. That’s more important than what he’s accused of? People with that frightening viewpoint are still fighting a civil war. They have to be contained.”

Does he fear that Trump might win a second term? “I don’t think he can, but the rest of us had better organise and vote in 2020. I hope people stop him ruining our nation.”

Abdul-Jabbar also worries that college sport remains as exploitative as ever. “It’s a business and the coaches, the NCAA and universities make a lot of money and the athletes get exploited. They make billions of dollars for the whole system and don’t get any. I’m not saying they have to be wealthy but I think they should get a share of the incredible amount they generate.”

In Coach Wooden and Me, he writes of how, in the 1960s, he was famous at UCLA but dead broke. “Yeah. No cash. It’s ridiculous. Basketball and football fund everything. College sports do not function on the revenue from water polo or track and field or gymnastics. It’s all down to basketball and football. The athletes at Northwestern tried to organise a union and that’s how college athletes have to think. They need to unionise. If they can organise they can get a piece of the pie because they are the show.”

The legendary Michael Jordan never showed the social conscience of Abdul-Jabbar and other rare NBA activists like Craig Hodges. But Abdul-Jabbar is conciliatory towards Jordan and his commercially-driven contemporaries. “I was glad they became interested in being successful businessmen because their financial power makes a difference. I just felt they should leave a little room to help the causes they knew needed their help. But Jordan has come around. He gave some money to the NAACP for legal funds, thank goodness.”

“People were amazed because I always used to be reading before a game – whether it was Sherlock Holmes or Malcolm X, John Le Carré or James Baldwin. But that was one of the luxuries of being a professional athlete. You get lots of time to read. My team-mates did not read to the same extent but I’m a historian and some of the guys had big holes in their knowledge of black history. So I was the librarian for the team.”

I tell Abdul-Jabbar about my upcoming interview with Jaylen Brown of the Boston Celtics – and how the 21-year-old has the same thirst for reading and knowledge. While enthusiastic about the possibility of meeting Brown when the Celtics next visit LA, Abdul-Jabbar makes a wistful observation of a young sportsman’s intellectual curiosity. “He’s going to be lonely. Most of the guys are like: ‘Where are we going to party in this town? Where are the babes?’ So the fact that he has such broader interests is remarkable and wonderful.”

Abdul-Jabbar acknowledges that his own bookish nature and self-consciousness about his height, combined with a fierce sense of injustice, made him appear surly and aloof as a player. It also meant he was never offered the head-coach job he desired. “They didn’t think I could communicate and they didn’t take the time to get to know me. But I didn’t make it easy for them so some of that falls in my lap – absolutely. But it’s different now. People stop me in the street and want to talk about my articles. It’s amazing.”

Most of all, in his eighth decade, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar “loves to lose myself in my imagination. It’s a wonderful place to go when you’re old and creaky like me. I see myself working at this pace [writing at least a book a year] but it’s not like I have the hounds at my heels. Since my career ended I’ve been able to have friends and family. My new granddaughter will be three this month. She’s my very first . So my life has expanded in wonderful ways. But, still, we all have so much work to do. The work is a long way from being done.”

[Donald McRae was born near Johannesburg in South Africa in 1961 and has been based in London since 1984.

He is the award-winning author of eight non-fiction books which have featured legendary trial lawyers, heart surgeons and sporting icons. He is the two-time winner of the UK’s prestigious William Hill Sports Book of the Year – an award won in the past by Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch and Laura Hillenbrand’s Sea Biscuit. As a journalist he has won the UK’s Sports Feature Writer of The Year – and was runner up in the 2008 UK Sports Writer of the Year – for his work in The Guardian. He was voted Sports Interviewer of the Year for three years running (2010-2012) at the Sports Journalism Association Awards.

Donald lived under apartheid for the first twenty-three years of his life. The impact of that experience has shaped much of his non-fiction writing. At the age of twenty-one he took up a full-time post as a teacher of English literature in Soweto. He worked in the black township for eighteen months until, in August 1984, he was forced to leave the country. His memoir Under Our Skin is based on these experiences.]