Net Neutrality: What Happens Next

The Federal Communications Commission has voted to repeal net neutrality, despite overwhelming public support for the regulation, which requires internet service providers like Verizon and Comcast to distribute internet access fairly and equally to everyone, regardless of how much they pay or where they’re located.

Despite last-minute requests to delay the December 14 vote from some Republican members of Congress, it went through as scheduled, thanks to the support of a much longer list of Republicans who favored the repeal and urged the vote to be held without delay. As had been heavily predicted for months, the vote was split 3-2 along party lines, with the FCC chair Ajit Pai and the other Republican members Michael O’Rielly and Brendan Carr voting for repeal and Democratic commissioners Mignon Clyburn and Jessica Rosenworcel voting to protect it.

The vote to repeal came in spite of overwhelming bipartisan support for net neutrality from the public, as the FCC was clearly determined to move ahead with the repeal. Tensions were high during the hearing — and at one point, in the middle of Pai’s remarks, the room was evacuated for about 10 minutes due to an apparent security threat.

We are being evacuated by security during net neutrality vote at FCC

— CeciliaKang (@ceciliakang) December 14, 2017

The implications of the repeal are vast and complicated. If it’s left unchallenged, it will almost certainly fundamentally change how people access and use the internet. But it could be a long time before we start to see the full effects of the FCC’s vote — and there’s even a ghost of a chance that the repeal might be overturned by the US Court of Appeals.

Here’s what you need to know about what could happen next.

1) What was the FCC actually voting on?

The FCC voted on the Restoring Internet Freedom Order, which concerned the repeal of Title II protection for net neutrality.

Title II is a decades-old regulatory clause that explicitly classifies internet service providers (ISPs) as telecommunications companies, meaning they’re essentially classified as utilities and subject to the same regulations that other telecommunication companies — also classified as utilities — must abide by. That basic regulatory standard is what people are referring to when they talk about net neutrality. Title II was first applied to ISPs in 2015, after a hard-won fight by internet activists.

Placing ISPs under Title II was the only legal way — barring the unlikely introduction and passage of Congressional legislation instituting complicated new regulatory procedures — in which these companies could be regulated. Now that the FCC has repealed Title II classification for ISPs, the ISPs will essentially be unregulated.

2) Why does it matter if ISPs are regulated or not?

Classifying ISPs as utility companies under Title II meant they had to treat the internet like every other utility — that is, just like gas, water, or phone service — and that they couldn’t cut off service at will or control how much of it any one person received based on how much that person paid for it. The idea was that the internet should be a public service that everyone has a right to use, not a privilege, and that regulating ISPs like utilities would prevent them from hijacking or monopolize that access.

The best argument for the rollback of this Title II protection is that maybe the internet isn’t a public service — maybe it’s just another product, and in a free market system, competition over who gets to sell you that product would ensure accountability and fair treatment among providers, if only due to economic self-interest.

But there’s a huge problem with that argument, which is that, as far as the internet is concerned, there really isn’t a free and open market. In the United States, competition among ISPs was driven down years ago thanks to the consolidated nature of internet broadband infrastructure, which has typically been owned by major corporations, shutting out local ISP competitors.

That’s why many people don’t really have much choice about which company they pay for internet access — that access has been monopolized by a handful of powerful companies. In fact, nearly 50 million households have only one high-speed ISP in their area.In other words, these particular utility companies, now unregulated, have free reign to behave like the corporate monopolies they are. Where net neutrality ensured the preservation of what’s been dubbed “the open internet,” its repeal will open the door for ISPs to create “an internet for the elite.”

3) What will happen to the internet without net neutrality protections in place?

Net neutrality mandated that ISPs display all websites, at the same speed, to all sources of internet traffic. Without net neutrality, all bets are off.

That means ISPs will be free to control what you access on the internet, meaning they will be able to block access to specific websites and pieces of software that interact with the internet.

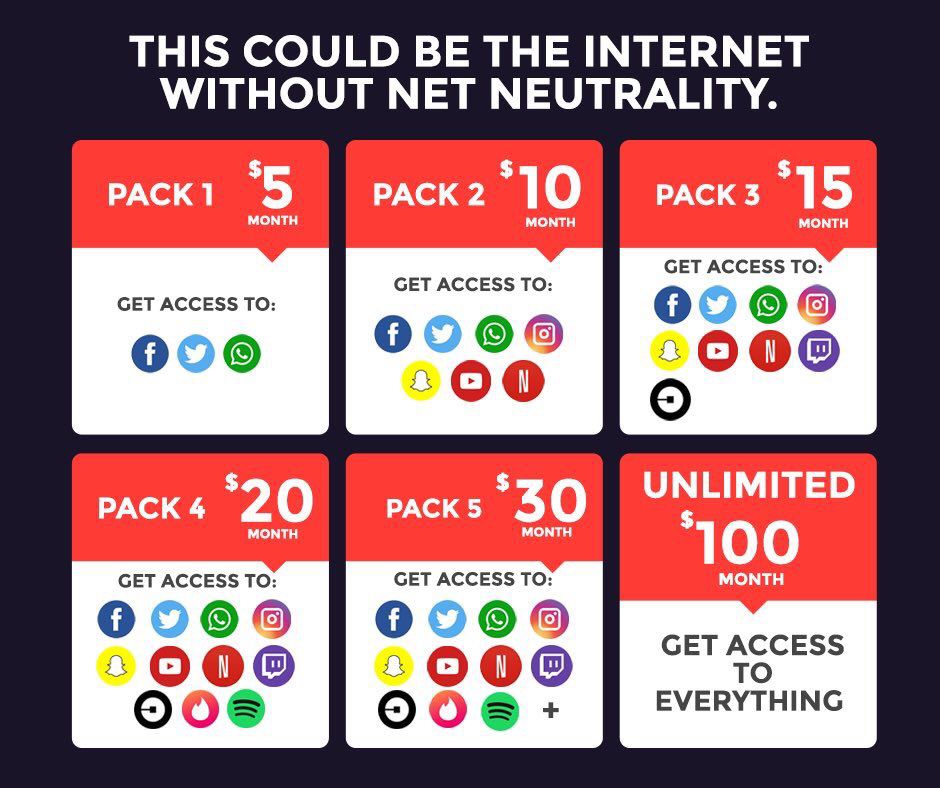

They might charge you more or less money to access specific “bundles” of certain websites, much as cable television providers do now — but instead of “basic cable,” you might be forced to pay for access to more than a “basic” number of websites, as this popular pro-net neutrality graphic illustrates:

ISPs will also be able to control how quickly you’re served webpages, how quickly you can download and upload things, and in what contexts you can access which websites, depending on how much money you pay them.

They’ll be able to charge you more to access sites you currently visit for free, cap how much data you’re allowed to use, redirect you from sites you are trying to use to sites they want you to use instead, and block you from being able to access apps, products, and information offered by their competitors or other companies they don’t like.

They can even block you from being able to access information on certain topics, news events, or issues they don’t want you to know about.

Finally, they’ll be able to exert this power not just over individual consumers, but over companies, as well. This could result in the much-discussed “internet fast lane” — in which an ISP forces a company like Twitter or BitTorrent to pay more for faster access for readers or users like you to its websites and services. Larger, more powerful companies likely won’t be hurt by this change. Smaller companies and websites almost definitely will be.

We already have a good idea of how these scenarios might play out, because in the era before net neutrality existed, ISPs tried instituting all of them: via jacked-up fees, forced redirection, content-blocking, software-blocking, website-blocking, competitor-blocking and still more competitor-blocking, app-blocking and still more app-blocking, data-capping, and censorship of controversial subjects.

If net neutrality advocates have made it seem like there’s simply no end to the worst-case scenarios that unregulated ISPs might subject us to, it’s because they’ve learned from experience. This history of ISP exploitation is a major reason that advocates for net neutrality fought so hard for it to begin with.

We also know that many ISPs, notably Comcast, already have their eyes on the aforementioned “fast lane,” also known as “paid prioritization.” (Disclaimer: Comcast is an investor in Vox’s parent company, Vox Media, through its NBC-Universal arm.)

And lest you believe that the current FCC is prepared to make sure that such offenses are fully sanctioned and dealt with by the government, think again. FCC chair Pai is a vocal proponent of letting ISPs self-regulate, and seems perfectly content to ignore their contentious and often predatory history.

Not only that, but the FCC is explicitly preventing state consumer protection laws from taking effect regarding net neutrality. That means that once the repeal is final, the rights of states to govern themselves won’t apply to protecting net neutrality. (Though California and Washington each vowed after the vote to try to protect it anyway.)

4) Who will be most affected by the repeal of net neutrality?

Women, minorities, rural communities, and internet developers will feel the fullest effects of this repeal.

The general argument among net neutrality advocates is that without an open internet, members of society who have historically been marginalized and silenced will be in danger of being further marginalized and silenced, or marginalized and silenced once more — particularly women and minorities.

We’ve seen in the past that ISPs can and will censor access to controversial subjects. Without regulation, situations could arise in which underprivileged or disenfranchised individuals and groups have less access to speak up or contact others online.

One worst-case scenario that we haven’t yet seen in America, but which is worth considering given the current heated political climate, is that ISPs could potentially play a role in limiting or marginalizing certain communities during times of urgency — for instance, an ISP might choose to block a mobilizing hashtag like #BlackLivesMatter at the start of an organic protest.

This might seem like a dire prediction, but there’s precedent for it: In 2011, the Egyptian government heavily censored certain websitesduring the Arab Spring. And in Turkey, under the administration of President Erdogan, the country has become notorious for censoring websites and blocking hashtags, at one point banning Twitter altogether.

Rural areas of the US — where internet access is already scarce due to a lack of ISPs operating there — will be further subjected to corporatization and monopolization of their internet infrastructure.

More than 10 million Americans already lack broadband access, and as the Hill notes in an overview of the potential impact of net neutrality’s repeal, “Good broadband is a small town’s lifeline out of geographic isolation, its connection to business software and services, and its conduit for exporting homegrown ideas and products.” Without regulatory inducements, corporate ISPs will have little incentive to develop infrastructure in such areas.

Another group that will be heavily impacted by net neutrality’s repeal — one that’s often overlooked but extremely crucial — is innovators and developers and people who create stuff for the internet. Tim Berners-Lee, creator of the internet as we know it, recently summed up the repeal’s potential effect on these developers:

If US net neutrality rules are repealed, future innovators will have to first negotiate with each ISP to get their new product onto an internet package. That means no more permissionless space for innovation. ISPs will have the power to decide which websites you can access and at what speed each will load. In other words, they’ll be able to decide which companies succeed online, which voices are heard — and which are silenced.

Again, this all sounds pretty dire — but that’s because it is. The people with the most expertise, the most investment in creating a progressive internet, and the strongest ability to advocate for an open internet could be prevented from doing their best work because of a lack of ability to pay for access to an ISP-controlled space.

It’s important to note, too, that because the nature of the repeal is unprecedented, we can’t necessarily predict every group and demographic that could potentially feel its impact.

5) Why did the FCC vote to repeal net neutrality when it had such overwhelming bipartisan support, and when the effects of a repeal seem so dire?

Pretty much everybody supports net neutrality — it’s one of the few bipartisan issues that most of Congress and most American citizens agree on. The glaring exceptions are the giant ISPs who are reigned in by the regulation.

Over the last nine years, Verizon, Comcast, and AT&T have collectively spent over half a billion dollars lobbying the FCC to end regulatory oversight, and especially to block or repeal net neutrality. They found a loyal friend in Pai, who was appointed to the FCC in 2012 by then President Barack Obama, and named chairman by President Donald Trump shortly after Trump took office in January. Pai previously worked for Verizon and voted against the 2015 net neutrality ruling as a minority member of the FCC, calling it a “massive intrusion in the internet economy.”

So Pai has basically always supported the repeal of net neutrality, despite the overwhelming public support for it. He believes the 2015 ruling was frivolous and unnecessary, and has also argued, in opposition to hard evidence, that investment in the internet shrinks when net neutrality is in effect. With Trump’s full backing, he has made undoing it a priority.

In fact, even though Pai is legally required to seriously consider the voice of the public when he makes decisions, he has made it clear that he never truly intended to consider most of the millions of comments submitted in support of net neutrality through the FCC’s website since it began the repeal process in May. That’s because the vast majority of those comments were duplicates that came through automated third-party advocacy websites. While many of them were likely submitted by spambots using fake or stolen identities and emails to file comments, many more of them were likely submitted by people using the tried-and-true method of sending a form letter to the government to express their opinions. Pai also rejected the form letters out of hand: Once the number of duplicate comments came to light, the FCC declared that it would be rejecting all duplicated comments as well as “opinions” that came without “introducing new facts.”

Essentially, even though nearly 99 percent of the unique comments that the FCC received were pro-net neutrality and anti-repeal, and even though the entire point of a democratic process is to allow people to express their opinions, the FCC chose to dismiss pretty much every opinion that was expressed, because spambots and auto-duplicated opinions were involved. FCC commissioner Rosenworcel, one of the commission’s two minority Democrats, acknowledged this during the December 14 vote to repeal, noting "the cavalier disregard this agency has demonstrated to the public.”

As Dell Cameron at Gizmodo put it, “To be clear, when the FCC says that it is ‘restoring internet freedom,’ it is not talking about your freedom or the freedom of consumers.”

6) What happens now, in the immediate aftermath of the vote?

A flurry of lawsuits from tech companies, internet activists, and think tanks will likely descend upon Washington — starting with a protective filing by internet activists that will appeal the FCC’s vote to prevent the repeal from immediately taking effect.

Mere hours after the FCC vote, the Attorney General of the state of New York announced a multi-state appeal of the ruling, to which a number of other states quickly signed on. The exact number of states participating in the appeal will grow over the coming weeks — technically after a suit is announced, the states (as well as any latecomers to any other lawsuits filed) will have 60 days to join in before the suit closes.

These lawsuits will petition the US Court of Appeals for a review of the FCC’s order. After a filing period of 10 days, all of the lawsuits will eventually be punted collectively to one of the Court of Appeals’ 12 circuit courts, and the ultimate outcome will be largely dependent on which court hears the appeals.

If the repeal does eventually go into effect, the FCC will institute one very thin piece of ISP regulation in place of net neutrality — a version of a 2010 transparency ruling that requires ISPs to inform consumers when the ISPs are deliberately slowing their internet speed. The FCC will be passing off the enforcement of this transparency stipulation to the FTC, in a long-planned and recently formalized agreement that will allow the two commissions “to work together to take targeted action against bad actors.”

7) When will the repeal go into effect?

We simply can’t know at this point. Establishing a workable timeline will depend on a whole heap of factors, such as which circuit court ends up hearing the appeals, whether there is a motion to relocate the appeals to another court, any motions or counter-motions filed on the appeals, and so forth. There’s also the likelihood that net neutrality advocates will ask for stays of the FCC’s ruling so that it can’t take effect while motions are still being heard and appeals are being deliberated.

Additionally, there’s one alternative to the appeals process that’s definitely a longshot, yet still a possibility: Congress could move to pass a joint resolution overturning the repeal and establishing new regulatory oversight. However, given how firmly many Republican politicians have stood behind Pai’s repeal campaign, this seems highly unlikely to happen unless the 2018 midterm elections result in a major upheaval of Congress, and could take years to hash out.

In a nutshell, we don’t know how long will it take to fight the repeal in the court system, so we can’t know when — or if — it will take effect. It’s likely that even if a court overturns the FCC’s decision, that court may only overturn part of it and not the entire thing.

What the final version of a net neutrality repeal might look like, and when it might take effect, are both unknown at this point, with the future of an open internet hanging in the balance.

Aja Romano writes about internet culture. follow her on Twitter @ajaromano.