How Stevie Wonder Helped Create Martin Luther King Day

On the evening of April 4, 1968, teen music sensation Stevie Wonder was dozing off in the back of a car on his way home to Detroit from the Michigan School for the Blind, when the news crackled over the radio: Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated in Memphis. His driver quickly turned off the radio and they drove on in silence and shock, tears streaming down Wonder’s face.

Five days later, Wonder flew to Atlanta for the slain civil rights hero’s funeral, as riots erupted in several cities, the country still reeling. He joined Harry Belafonte, Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, Eartha Kitt, Diana Ross and a long list of politicians and pastors who mourned King, prayed for a nation in which all men are created equal and vowed to continue the fight for freedom.

Wonder was still in shock—he remembered how, when he was five, he first heard about King as he listened to coverage of the Montgomery bus boycott on the radio. “I asked, ‘Why don’t they like colored people? What’s the difference?’ I still can’t see the difference.” As a young teenager, when Wonder was performing with the Motown Revue in Alabama, he experienced first-hand the evils of segregation—he remembers someone shooting at their tour bus, just missing the gas tank. When he was 15, Wonder finally met King, shaking his hand at a freedom rally in Chicago.

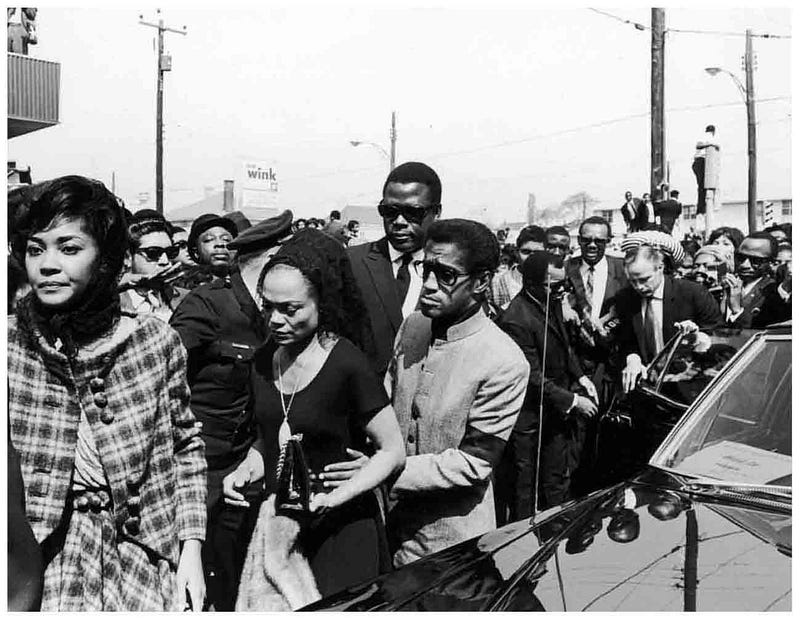

Nancy Wilson, Eartha Kitt, Sammy Davis Jr, Sidney Poitier, Berry Gordy Jr, and Marlon Brando arrive at the funeral for Dr. King

At the funeral, Wonder was joined by his local representative, young African-American Congressman John Conyers, who had just introduced a bill to honor King’s legacy by making his birthday a national holiday. Thus began an epic crusade, led by Wonder and some of the biggest names in music—from Bob Marley to Michael Jackson—to create Martin Luther King Day.

To overcome the resistance of conservative politicians, including President Reagan and many of his fellow citizens, Wonder put his career on hold, led rallies from coast to coast and galvanized millions of Americans with his passion and integrity.

But it took 15 years.

In the immediate wake of King’s death, the political establishment was more concerned with keeping things calm, tamping down unrest, and arresting rioters and activists. It was a violent year—that summer the Democratic convention in Chicago exploded in chaos and another inspiring leader, Robert F. Kennedy, was killed by an assassin. The country seemed on the verge of civil war.

Conyers’ bill languished in Congress for over a decade, through years of anti-war protests, Watergate and political corruption, stifled by inertia and malaise at the end of the 1970s. The dream was kept alive by labor unions, who viewed King as a working-class hero, with protests that slowly built up steam. At a General Motors plant in New York, a small group of auto workers refused to work on King’s birthday in 1969, and thousands of hospital workers in New York City went on strike until managers agreed to a paid holiday on the birthday. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, led a birthday rally that year in Atlanta, where she was joined by Conyers and union leaders. By 1973, some of the country’s largest unions, including the AFSCME and the United Autoworkers, made the paid holiday a regular demand in their contract negotiations.

Finally in 1979, President Jimmy Carter, who had been elected with the support of the unions, endorsed the bill to create the holiday. Carter made an emotional appearance at King’s old church, Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. But Congress refused to budge, led by conservative Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, who denounced King as a lawbreaker who had been manipulated by Communists. The situation looked bleak.

By then, Wonder had matured from a young harmonica-playing sensation to a chart-topping music genius lauded for his complex rhythms and socially-conscious lyrics about racism, black liberation, love and unity. He had kept in touch with Coretta Scott King, regularly performing at rallies to push for the holiday. He told a cheering crowd in Atlanta in the summer of 1979, “If we cannot celebrate a man who died for love, then how can we say we believe in it? It is up to me and you.”

That summer, Wonder called Coretta Scott King, telling her, “I had a dream about this song. And I imagined in this dream I was doing this song. We were marching—with petition signs to make for Dr. King’s birthday to become a national holiday.”

King was touched but she didn’t have much hope, telling Wonder, “I wish you luck, you know. We’re in a time where I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

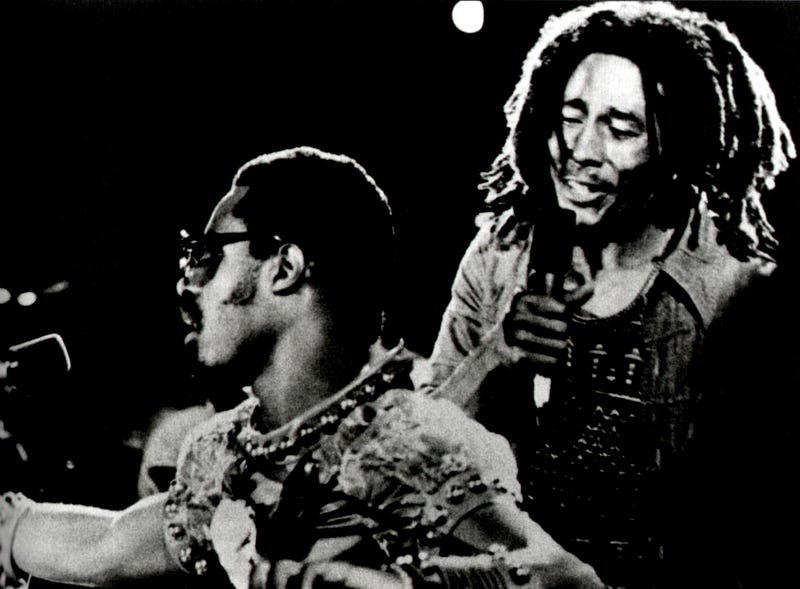

That August, during a memorable appearance with Barbara Walters on 20/20, Wonder played “Happy Birthday” on the keyboards, announcing that he would soon start a four-month tour with Bob Marley that would lead into a mass rally to push for the holiday. The location was ripe with symbolism—the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where King had given his famous “I Have A Dream” speech. It was just a few months before the election that put Ronald Reagan in the White House, and Wonder was concerned about the “disturbing drift in the country towards war, bigotry, poverty and hatred.”

Stevie performs alongside Bob Marley

Tickets sold out for the concerts, buzz was building, but then disaster struck — Marley checked into a hospital in New York with the cancer that would cause him to perish just six months later. Wonder asked songwriter and poet Gil Scott-Heron, known for his polemic “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” to fill in for the ailing reggae superstar. The tour was the highlight of Scott-Heron’s career, he later wrote in The Last Holiday, his book devoted to King and Wonder for inviting him to join the cause. At the end of every show, he would join Wonder on stage to lead the audience in a rousing rendition of “Happy Birthday.”

The tour was full of extremes. When they played at Madison Square Garden in November, Wonder delighted the huge audience with a surprise guest—the Prince of Pop. Michael Jackson slid on to stage during the reggae rhythm of “Master Blaster” and the crowd screamed as he twirled “like a boneless ice skater,” remembered Scott-Heron. And when they played in Los Angeles a week later with Carlos Santana, Wonder had to somberly announce John Lennon’s killing that night to a stunned audience that soon started wailing and breaking down in tears. In a moving elegy, Wonder talked about their friendship and praised Lennon’s integrity, connecting him to King, drawing “a circle around the kind of men who stood up for both peace and change” and making the upcoming rally even more significant.

He spoke eloquently: “Why Stevie Wonder, as an artist? Why should I be involved in this great cause? …As an artist, my purpose is to communicate the message that can better improve the lives of all of us. I’d like to ask all of you just for one moment, if you will, to be silent and just to think and hear in your mind the voice of our Dr. Martin Luther King.”

Stevie Wonder, Gil Scott Heron, Reverend Jesse Jackson, Gladys Knight and Sam Courtney at a press conference at Rafu Gallery, Washington, DC, January 15, 1981.

Despite the outpouring of support—and millions of signatures gathered by Wonder and his team—Congress continued to debate the issue. President Reagan opposed the holiday, citing the cost of another national day off and suggesting instead a scholarship program for young blacks. Wonder came back the next January for another rally, and finally hearings resumed in 1982 and 1983. Though both Coretta Scott King and Wonder gave moving testimony, conservatives were on fire, led by Jesse Helms. During an intense filibuster, the North Carolina Republican labeled King a “Marxist-Leninist” whose “whole movement included Communists,” and called on the FBI to release its records on King. His language was so hateful that at one point New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan angrily threw a batch of Helms’s documents on the floor, calling it a “packet of filth.”

At that point, the rhetoric had grown so incendiary that even moderates in opposition felt compelled to express their support for the holiday. The bill passed, 78 to 22. Reagan signed the bill into law in November, 1983 but the holiday was not officially observed until the third Monday of January, 1986. For many years to come, certain states refused to honor the holiday until in 2000 South Carolina became the final state to recognize Martin Luther King Day.

Coretta Scott attends the signing of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day by President Reagan on November 2, 1983 | President Obama presents the Medal of Freedom to Stevie Wonder in the White House on November 24, 2014. The Medal of Freedom is the country’s highest civilian honor.

Stevie Wonder continues to celebrate King’s birthday with frequent performances. On November 24, 2014, he was honored with the Congressional Medal of Freedom at the White House by President Obama, who told the singer that the first record he ever bought was by Wonder.