Dr. Victor Sidel, Who Fostered Health and Peace, Dies at 86

Dr. Victor Sidel, a leading public health specialist whose concerns ranged from alleviating the effects of poverty in the Bronx, where he worked for many years, to raising alarms about the potential impact of nuclear war, died on Jan. 30 in Greenwood Village, Colo. He was 86.

His son Mark confirmed the death.

As a founding member of Physicians for Social Responsibility and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985, Dr. Sidel voiced his apprehensions about nuclear proliferation as a public health issue for more than 50 years. He served as president of the former organization and co-president of the latter.

In a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1962, Dr. Sidel, Dr. H. Jack Geiger and Dr. Bernard Lown painted a grim picture of fatalities and injuries in the Boston area from a nuclear attack and posed ethical questions for surviving doctors.

“Does the physician seek shelter?” they asked, adding, “If the physician finds himself in an area high in radiation, does he leave the injured to secure his own safety?”

And in speeches beginning in the mid-1980s, Dr. Sidel (pronounced sy-DELL) used a metronome to stress what he described as the imbalance between worldwide spending on arms and health care. With the metronome set at one beat a second, Dr. Sidel explained that with every beat, a child died or was permanently disabled by a preventable illness, while $25,000 was spent on weaponry.

“Tiny fractions of that spending could, of course, produce remarkable changes in health,” he told the American Public Health Association in Washington in 1985, when he was its president. “The cost of one half-day of world arms spending could pay for the full immunization of all the children in the world against the common infectious diseases.”

In 1988, when he brought the metronome to a speech in Rochester, he wondered aloud if arms spending had damaged the world even without the dropping of nuclear bombs.

“To what extent are we now living in the rubble caused by the diversion of resources?” he asked.

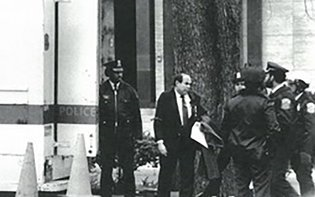

Dr. Sidel was among 139 people arrested, including the astronomer Carl Sagan, during a protest organized by the American Public Health Association at a nuclear test site in Mercury, Nev., in 1986.

During the demonstration, the Department of Energy conducted an underground test 50 miles away.

“P.S.R. kept alive discussion of the medical risk of nuclear weapons, nuclear tests and nuclear power plants,” he told the group’s San Francisco chapter in 2011. “If P.S.R. had not existed, a medical voice in opposing these risks would not have been effectively heard.”

His interest in world affairs was wide-ranging. A year before the demonstration in Nevada, he had been arrested during a protest in Washington against South Africa’s apartheid policies. (A photograph of him being arrested hung in his office at Montefiore.)

Despite the specter of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, Dr. Sidel was an optimist and innovator who preached that community outreach was a critical factor in treating vulnerable populations.

As chairman of the department of social medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx for 16 years, he developed community health centers, trained interns and residents to study the economic and social factors that affected local residents’ health, initiated a project to improve the health of children in local day-care centers, and worked on programs to address prisoners’ health.

“I worked at Rikers and ran a health service, and he was so supportive,” Dr. Steven M. Safyer, president and chief executive of Montefiore Medicine, said of Dr. Sidel. “He’d say that we’re locking up all these people but the reason they didn’t get through school is they lived in poverty. He was always thinking about the bigger picture.”

Victor William Sidel was born in Trenton on July 7, 1931. His father, Max, and his mother, the former Ida Ring, Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, met in Philadelphia and opened a pharmacy in Trenton, where young Victor worked and saw the effects of poverty and poor nutrition on the store’s customers.

He received a bachelor’s degree in physics from Princeton University, where, he recalled, Albert Einstein once attended his professor’s classroom demonstration of surface tension. “So I got to shake hands with Albert Einstein and have not washed my hands since,” he said in an interview in 2013 for the journal Social Medicine.

After graduating from Harvard Medical School, where he worked in the biophysical laboratory studying the membrane structure of red blood cells, he started his residency at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital) in Boston. He spent two years at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., before returning to Brigham to complete his residency. By then, Dr. Sidel had been invited by Dr. Lown, a cardiologist at Harvard, to join what became Physicians for Social Responsibility. Dr. Lown was a co-founder.

Moving away from work as a clinician — “I want to prevent the wounds, not simply treat them,” he told Social Medicine — he became chief of the community medicine unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1967 and, in 1969, chairman of Montefiore’s social medicine department, where he was also a professor of community health.

As part of a delegation of four American doctors invited to China in 1971 by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dr. Sidel studied that country’s health-care system several months before President Richard M. Nixon’s historic visit.

Dr. Sidel’s interest in community health delivery took him to see China’s so-called barefoot doctors, agricultural workers in the countryside who received a few months’ training to offer basic health care.

His experience in China — he visited several more times — inspired the creation at Montefiore of a Bronx network of lay health workers to promote disease prevention through education and peer counseling.

Mark Sidel said his father had steered clear of having his work used for propaganda.

“He wouldn’t report anything about Chinese health care that wasn’t based in science and statistics,” Mr. Sidel said in a telephone interview, “and everywhere he went, he wanted to know about rates of immunization and infant mortality.”

In addition to his son Mark, Dr. Sidel is survived by another son, Kevin, and three grandchildren. His wife, the former Ruth Grossman, a writer and sociology professor at Hunter College, died in 2016.

Dr. Barry Levy, an adjunct professor of public health at Tufts University, said Dr. Sidel had viewed health as a “basic human right.”

In a eulogy, Dr. Levy, who edited several books with Dr. Sidel, said: “Vic taught us that health, peace and social justice were not isolated concepts, but tightly woven together. I can still hear him saying there cannot be health without peace and social justice, and there cannot be peace and social justice without health.”