As Germany Honors Those Who Fought Fascism, We Must Honor Those Who Fought White Supremacy

Hans Horn and his wife Traudel promised it would be a tour of Berlin's socialist history, and so it was. Twice I spent a long day with them on the U-Bahn and S-Bahn, trying to hear what they explained over the roar of the subway as we hurtled from monument to monument, cemetery to cemetery.

Berlin is a city of revolution and anti-fascist struggle. It is also a city of graves. Trees on one beautiful leafy hill cover the remains of 183 Berliners who fought and died on the street barricades in 1848. When they were interred in the Cemetery of the March Revolution, 80,000 Berliners looked on. Thirty-three others are also buried there, who died in the streets during the Revolution of 1918-19. Treptower Park's giant, cold spaces cover even more bodies -- 7,000 of the 80,000 soldiers who died in the final battle to wrest Berlin from the Nazis.

Hans and Traudel are certainly not worshippers of the dead. For these two leftwing Berliners, the graves form part of a collective memory of socialism. They force an acknowledgement of the ideas those revolutionaries died to defend. Fascism's armies sought to bury those ideas forever, along with the people who held them, in the Nazis' "thousand-year Reich." Treptower's buried soldiers were among the 50 million people who died stopping them.

The city's monuments, the Horns argue, keep people from forgetting whose ideas fueled that revolutionary fire: Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Ernst Thälmann and Käthe Kollwitz.

As we visited these sites, I kept thinking of the intense fights we've had recently in the US over our own monuments. For the last two years especially, people have fought -- not to preserve monuments to a progressive past, but to get rid of those that raise up slavery and oppression. The very fact we've had these struggles is evidence of a change in power.

Monuments are a lesson in power. When anti-fascists had power in Berlin, they built the monuments to those who fought Nazism. But even when power shifted after reunification, and anti-fascist monuments were endangered, they could still be preserved by popular struggle, as they were in Berlin.

The monuments erected to memorialize the defenders of slavery and genocide in our country also tell us about power, especially, who held it during the Jim Crow and Cold War years. But now our communities are showing that there are new limits, forcing the removal of statues and flags honoring the Confederacy. The monuments to those who waged the war to make the Philippines a colony, and those who inflicted genocide on the Indigenous people of California, are still standing in San Francisco. But perhaps we can see a day now when they won't be so honored.

Looking at the way Rosa Luxemburg's name is attached to so many Berlin places and institutions, I couldn't help thinking about how we remember our own peoples' history. Where are the statues to murdered slaves, and to those who led the fight against that oppression? To those who died in the genocide of Native Americans?

At the Mission San Juan Bautista graveyard, Spanish padres deposited the bodies of the Ohlone people they'd enslaved, who died of disease and overwork. Those graves were anonymous for two centuries. Now there's an acknowledgement of who might be buried there, but still, their names are absent. There are no "stumbling stones" (as you see in Berlin sidewalks) that keep alive the personalities of those who lived in the houses from which Nazis dragged people to their deaths.

We need the same feeling about memorials to the slaves who perished on the plantations that Germans have for those who perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Those who fought to end slavery in the Union Army (including those German revolutionaries of 1848 who'd fled to Texas) need the same honor people in Berlin accord to the Red Army that liberated their city.

Sometimes I dream about what a socialist government might do where we live. Would we have a statue of Eugene Debs, with his words from Canton jail protesting the slaughter of World War I? Would it be on the Washington Mall, as Käthe Kollwitz's denunciation of war is on Unter den Linden, in the centermost part of Berlin? How about Lucy Gonzalez Parsons, a Black/Latina woman who led the fight for the eight-hour day after her husband was murdered by Chicago's one-percenters for organizing workers and challenging predatory capitalism? Could we put her words on stones that would cross a Times Square pedestrian mall renamed for her, as the eponymous Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz remembers Gonzalez's contemporary, who fought for the same ideals?

Berliners even remember their radical history in the Reichstag -- the equivalent of Washington's Capitol building. The black bands below the names of Germany's Communist and Socialist deputies of the '30s, and the dates of their execution, show the price they paid. Did we also have socialist Congress members like those whose names are honored in the Reichstag? How do we remember Vito Marcantonio and Victor Berger, and the others who held the same ideas and defended them in our own Congress? Or Ben Davis, who served on the New York City Council?

In Treptower Park, I remembered the photographs of the US and Soviet soldiers as they met at the Elbe River in 1945, when there was no longer an inch of Germany controlled by the Nazis. We were allies then. The photographs show the happiness and weariness of people fighting in the same anti-fascist cause, seeing across that river those who'd fought with them.

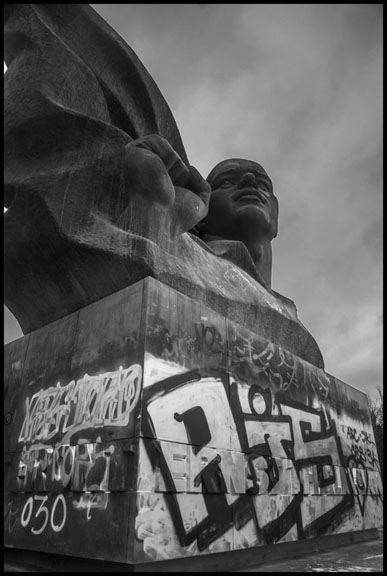

My father fought in that war, on the same side as the Red Army soldiers buried in Treptower Park. My mother edited books filled with the revolutionary ideas that inspired those who fought to end fascism. When I was a kid, we listened to a scratchy record of the Songs of the Lincoln Brigade -- those US radicals who fought fascism in the Spanish Civil War. In "Freiheit," a verse sings of the Thälmann Battalion. All of a sudden, in Berlin, there I was, looking at his statue, albeit with its lower part covered in graffiti.

The Cold War taught us to see people on our own side -- those who fought for the same ideals -- as enemies. It inculcated a level of fear that made us blind to who those dangerous Germans and Soviets were. When we were taught to fear Rosa Luxemburg, or to banish her from history books, it became much easier to banish Lucy Gonzalez Parsons as well. Perhaps having statues to Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, instead of to the Texas Germans who fought in the Union Army, is connected to the absence of any acknowledgement in this country of the Soviet soldiers who died, as soldiers from the US did, ending Nazism.

It's all about class and race, and who holds power when those monuments are erected. Berliners can see it, walking through their city every day.

The grave of Wilhelm Krause in the Cemetery of the March Revolution, next to the Volkspark (People's Park) in Berlin's Friedrichshain district. The tombstone calls him a "beloved son" and a "freedom fighter." Insurrections took place in March of 1848 against monarchy and repression all over Europe, and people fought on the barricades in many German cities. Prussian soldiers fired on the people of Berlin, and 183 were buried in the cemetery. Many of those killed were workers. After 1848, many German revolutionaries fled to the United States, especially to Texas, where they helped start the US's first socialist organizations. During the Civil War, they raised troops to fight slavery in the Union Army.

The statue of the "Red Sailor" with his rifle over his shoulder in the Cemetery of the March Revolution. It commemorates those who died in the Revolution of 1918-19, when after World War I, German revolutionaries tried to set up a socialist government. The Freikorps, a paramilitary group organized by Germany's Social Democratic government after the German Army collapsed, fired on the people and put down the revolution. After the fall of Nazism, the East German government restored the cemetery's graves and commissioned the statue by Hans Lies.

This monument marks the place where Rosa Luxemburg was killed by the Freikorps, and her body thrown into the Landwehr Canal in Berlin's Tiergarten, on January 15, 1919. She was a leader of the revolution, a founder of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and a feminist theoretician of the socialist movement. After the fall of Nazism, West Berlin's government refused to place a monument to her in the Tiergarten, which lay under their control in the West sector. After reunification, the petition of many Germans led to the commemoration. Clara Zetkin, her fellow revolutionary, said, "With a will, determination, selflessness and devotion, for which words are too weak, she consecrated her whole life and her whole being to socialism."

The memorial in the Tiergarten to Karl Liebknecht, who proclaimed the Free Socialist Republic in Berlin on November 9, 1918. Socialist republics were also organized in Bremen, Munich and other German cities. After he and Luxemburg were captured and tortured by the Freikorps, he was beaten with a rifle butt and shot. After their execution, the Freikorps killed thousands of KPD members and other revolutionaries, and suppressed the revolutions. The Nazis merged the Freikorps into the SA (Brownshirts) at the beginning of their regime. Like Luxemburg's, his memorial was also put up only after the reunification of Berlin.

Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, between the Mitte and Friedrichshain neighborhoods of the former East Berlin, was named in her honor by the government of the former German Democratic Republic. In the stones of the plaza are famous quotes from her writing. As the revolution briefly took power in January 1919, Luxemburg declared, "Today we can seriously set about destroying capitalism once and for all ... our solution offers the only means of saving human society from destruction." She was a revolutionary democrat: "The masses are in reality their own leaders, dialectically creating their own development process. The more that social democracy develops, grows, and becomes stronger, the more the enlightened masses of workers will take their own destinies, the leadership of their movement, and the determination of its direction into their own hands."

Statues of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who as theoreticians analyzed capitalism and argued that labor creates all value, and that social development is the product of people's class relations. The statues sit near Alexanderplatz, the center of East Berlin during the years when the city was divided.

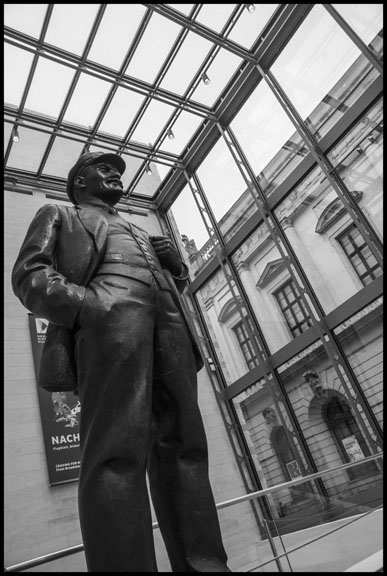

A statue of V.I. Lenin. Originally, this statue by Soviet sculptor Matvey Manizer stood in Pushkin, near Leningrad in the Soviet Union. The German Wehrmacht took it to Berlin as war booty during their invasion. The Nazis almost melted it down in 1943, but it was too large. After the war, it was rescued and placed in the lobby of the German Historical Museum, which was in East Berlin during the years of the German Democratic Republic. After German reunification, the statue was moved from the lobby to a location further inside the museum, but public pressure prevented its removal.

When the Reichstag, Germany's parliament building, was rebuilt after German reunification, a room was constructed holding plaques bearing the names of every deputy, from the end of World War I to the time of reunification. The names of those deputies murdered by the Nazis have a black band under their name.

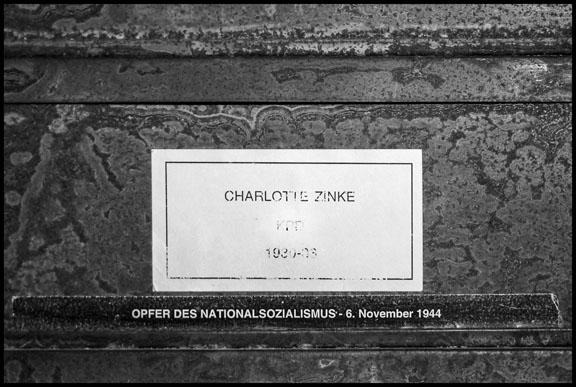

This plaque honors Charlotte Zinke, in the room devoted to past members of the German parliament. The plaque has the initials of her party, the KPD or Communist Party of Germany, and the years she was a deputy -- 1930-33. In 1944, Zinke was arrested by the Gestapo, and taken to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she was murdered. In a last note smuggled out to her husband, she says, "Hopefully I have the strength to endure it all."

Two rare photographs taken by a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp show Nazi guards burning bodies. The two photographs hang on a wall in the lobby of the Reichstag building.

Hans Werner Horn, a German professor, walks between the stones of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, in central Berlin. The memorial, designed by architect Peter Eisenman and engineer Buro Happold, is made up of 2,711 concrete slabs of different heights, with walkways between them, symbolizing the concentration camps where 6 million Jews were killed.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, in central Berlin, was criticized by Björn Höcke, a leader of Germany's proto-fascist party, the Alternative for Germany. He said, "Germans are the only people in the world who plant a monument of shame in the heart of the capital," and that Germany needed a "180-degree turn" in its attitude toward World War II. Afterwards, anti-fascist activists built a replica of the memorial in a lot next to his house in Thuringia.

Two stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, in the cobblestone street in the Berlin neighborhood of Friedrichshain. They say: "Here lived and worked Dr. Bernhard Britzmann, who was denounced, fled into death 11/17/1936, investigative prison in Alt-Moabit," and "Here lived Ella Britzmann, born Kempler, deported 11/17/1941, Kowno Camp 9, murdered 11/25/1941." This project, placing concrete cubes and a metal plaque outside the homes and workplaces of victims of Nazism, was begun by artist Gunter Demnig in 1992. Over 56,000 have been placed, not just in Germany, but in 22 European countries. When fascists would stumble in Nazi Germany, they'd say, "A Jew must be buried here," and when the Nazis desecrated Jewish graveyards, they would turn the gravestones into paving in the sidewalks.

The memorial to Ernst Thälmann, the son of a farmworker and shopkeeper. As a boy, he participated in the Hamburg dockworkers' strike of 1896, and was a soldier during World War I. After Germany's defeat, he participated in the Hamburg Workers and Soldiers Committee during the revolution of 1918-19, and later, the Hamburg Uprising in 1923. He was elected a deputy in the Reichstag in 1924, and became head of the Communist Party of Germany during the years of the Weimar Republic. In 1933, after Hitler took power, he was arrested. He was held in solitary confinement in Moabit prison for the next 11 years, and finally executed in the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1944. During the Spanish Civil War, the German section of the International Brigades was named the Thälmann Battalion. Five thousand Germans went to fight fascism in Spain, where 3,000 died. After German reunification, there were proposals to dismantle the memorial to Thälmann, erected in 1966 in the former East Berlin, but popular protest prevented it.

The Volksbühne, or People's Theater, on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz in the Mitte neighborhood, formerly part of East Berlin. More than a building, it was a project to create a theater of the people, with socially relevant plays and cheap admission so that workers could attend. It started just before World War I. The building was damaged during bombing in World War II and rebuilt afterwards. Through the 1990s and 2000s, its director was Frank Castorf, who maintained its reputation for experimental theater accessible to working-class audiences. When the city government announced it was replacing him with the director of London's elite Tate Modern Museum, activists occupied the theater in protest. On one side of the Platz is the building housing Germany's left-wing party, Der Linke, and which was the former headquarters of the KPD before the Nazis took power.

The monument to Soviet soldiers in Treptower Park, in former East Berlin. Over 7,000 of the 80,000 Soviet soldiers who died in the liberation of Berlin from Nazi armies are buried in the memorial. After unification of Germany, conservative authorities sought to get rid of it, but were prevented by public outcry. It is now jointly administered by Germany and Russia.

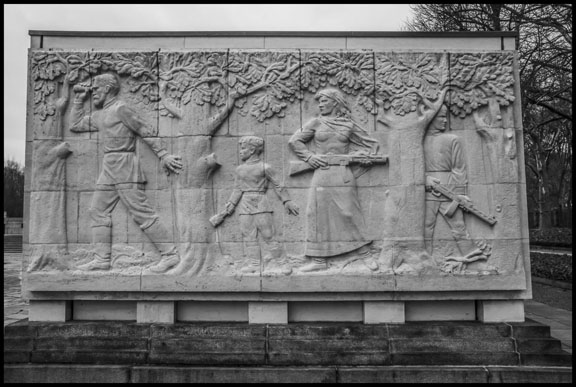

One of the 16 panels in the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park depicts the partisan resistance to Nazi occupation. The stone for the memorial came from the Nazi Reich Chancellery, which had been demolished. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the memorial was vandalized -- an act credited to fascists. Over a quarter of a million people came to demonstrate against the vandalization on January 3, 1990. Every May 9, the anniversary of the surrender of the Nazi armies, a vigil takes place at the memorial organized by the Anti-Fascist Coalition of Treptow.

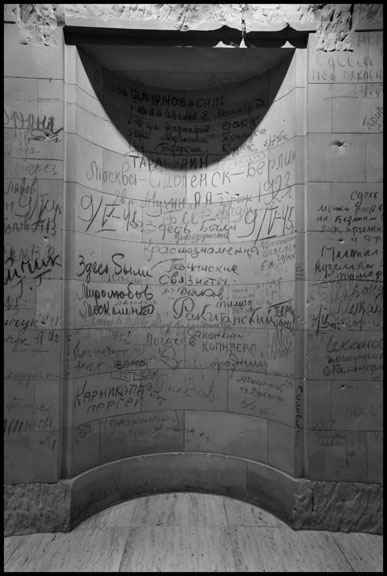

When the Reichstag building was restored in 1999, the team led by architect Norman Foster preserved elements from the old building, which had been partially destroyed in World War II and lay unused for years. In preserving historic elements of the building, the architects kept the graffiti written in Cyrillic by Soviet soldiers after the fall of Berlin in 1945. In addition to their names, some soldiers wrote slogans, such as "Hitler Kaputt!"

The "Woman with Her Dead Son," a sculpture of Käthe Kollwitz, in the building devoted to this one work on Unter den Linden in central Berlin. From the late 1800s through the years after World War I, Kollwitz produced etchings, lithographs, woodcuts and other graphic work depicting the oppression of workers and peasants, and the horror of war. "I was powerfully moved by the fate of the proletariat and everything connected with its way of life," she said, reflecting her communist beliefs. She became so well-known and respected that even though the Gestapo threatened her, the Nazis were afraid of the international outcry that would have followed her arrest. She continued to live in Germany until her death 16 days before the end of the war. The sculpture, an outcry against war, was placed in the New Guardhouse, a monument to the victims of fascism and militarism during the era of the German Democratic Republic, after reunification. An underground room contains the remains of an unknown soldier and a resistance fighter, and soil from concentration camps.

[David Bacon is a writer and photographer, and former union organizer. He is the author of several books on labor, migration and the global economy, including The Children of NAFTA, Communities Without Borders, Illegal People and The Right to Stay Home. His photographs and stories can be found at here and here.]

© Copyright David Bacon

Reprinted with permission of the author and Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

Truthout publishes a variety of hard-hitting news stories and critical analysis pieces every day. To keep up-to-date, sign up for our newsletter by clicking here!