Labor and the Long Seventies

Democracy is bad for business. Fearful of what employees would do if they had power in the workplace, corporations have used every strategy conceivable to keep them in line and democracy in check.

And yet there was a time, hard as it might be to imagine now, when labor was on the ascendency. Many have even claimed that there was a social compact between capital and labor following the end of the Second World War: employers dumped the Pinkertons for productivity gains and workers agreed to swap picket signs for picket fences and the promise of an ever-increasing quality of life. Then, somewhere between the Tet Offensive and the Reagan Revolution, it all started to come crashing down for the labor movement — and has yet to recover.

What happened and why? Lane Windham, associate director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, offers some intriguing answers in her new book, Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide.

Labor Notes staff writer Chris Brooks recently spoke with her about the promise and peril of union organizing in the “long 1970s” and how that history should inform strategies for building worker power today.

* *

Chris Brooks (CB): Your book describes unions as the “narrow door” through which workers accessed our nation’s fullest social welfare system. What do you mean?

Lane Windham (LW): If you are German or French, you don’t have to join a union to have access to health care or retirement. Those are benefits provided as a matter of citizenship. In our country, employers provide those benefits to workers. How do we ensure that corporations step up to play this role? Through firm-level collective bargaining. So unions play a critical role in our social welfare system — they do the redistribution work that governments do in many other countries.

There are three ways that workers can access this social welfare system: they can form a union, they can get a job in a company that is already unionized, or they can get a job at a company that is matching union wages and benefits. Either way, someone at sometime had to organize a union for this to be possible.

So organizing a union is the narrow door through which working people access our nation’s most robust social welfare benefits. My book focuses on the 1970s, a period where we see women and people of color driving a wave of union organizing after gaining new access to the job market as a result of the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

CB: You describe Title VII of the Civil Rights Act as the single biggest challenge to employers’ workplace power since the passage of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act. Why?

LW: The National Labor Relations Act, or the Wagner Act, was a huge challenge to corporations. It provided a legal process through which workers can win a union and compel companies to negotiate a contract with them. In many ways, it was the answer to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s big labor question: how are we going to deal with the contradiction between the promise of democracy and the realities of industrial capitalism?

The Wagner Act was a compromise that excluded many women and people of color by excluding domestic service and agricultural jobs. This was one of the major limitations of the New Deal promise, but with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, all those workers who had been relegated to the margins of industrial capitalism suddenly had access to jobs in the core.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination on the grounds of race, sex, color, religion, or national origin. The narrow door was suddenly open to everybody, and you see this great rush of women and people of color into unions. In 1960, only 18 percent of the nation’s union members were women, but by 1984, 34 percent of union members were women. By 1973, a full 44 percent of black men in the private sector had a union.

CB: When I think of the working class in the 1970s, the first image that comes to my mind is Archie Bunker: the white, blue-collar, hard-hat wearing conservative union member that wants to beat up hippies. But you argue for a very different image of the working class in this period.

LW: Today’s working class is majority women and disproportionately people of color. That change started in the 1970s.

On the show, All in the Family, Archie Bunker was a loading dock supervisor. In my book, I feature the story of Arthur Banks, an African American who was an actual loading dock supervisor at a department store in Washington DC. He surreptitiously supported the union, even though it could have gotten him fired, because he knew it would lift wages for everyone, supervisors included. So Archie Bunker is the image that has stayed with us, but Arthur Banks is the image I argue we should have.

CB: How were people like Arthur Banks informed and influenced by the social movements of the preceding decade?

LW: An entire new generation of union activists were coming of age in an era in which their consciousness of their rights had been dramatically expanded. The civil rights and women’s movements were fuel to the labor movement: if racism and sexism are no longer acceptable, then why should we accept the power of the boss?

One of my favorite quotes in the book is by a shipyard worker named Alton Glass. He had followed his father into the Newport News shipyard. Glass’s dad was the son of sharecroppers and had spent most of his life in the segregated South. In the 1970s, Glass was a young union activist who took on racism and unfair treatment in the shipyard, and he had this great quote: “Where my dad told me to shut up, I wouldn’t shut up. And my supervisors, who were older and white, would expect me to shut up. And I wouldn’t.” Glass had a different experience coming out of these rights movements that informed his union activism. He would later go on to serve as the president of his local Steelworkers union.

Many women in the 1970s also took the ideas of equity from the previous decade’s women’s movement and used them in the office sphere to demand raises and respect and access to better jobs. They challenged workplace culture. Many women began refusing to act like a coffee-fetching “office wife” for their boss. Millions of women joined the workforce in this decade, and many were at the forefront of union organizing campaigns.

You saw this in the 1979 blockbuster Norma Rae, which was based off of the famous textile workers’ organizing campaign at the J. P. Stevens mattress manufacturing plant in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. Women were definitely key to that campaign, especially black women. It was actually won because of the dramatic influx of black workers to the facility, who brought with them an interest in unionizing.

CB: You argue that contrary to what many believe, there was no decline in labor organizing in this period — that the 1970s saw not only an “unheralded wave” of private sector workers voting in union elections, but also the largest strike wave since 1946 and the birth of multiple union reform movements.

LW: A lot of the historiography on the 1970s is focused on decline. Jefferson Cowie, in his book Staying Alive, talks about that decade as “the last days of the working class.” Cowie was just picking up on the dominant narrative among labor historians, who have almost universally focused on the percentage of the workforce that had a union or the number of workers winning union elections. Both of those figures drop in this decade.

I tell a different story, and I do it by looking at different data. I looked at National Labor Relations Board election records and at the number of workers voting in union elections across the decades, regardless of whether they won or not. If you look at these figures, what you see is that the number of workers voting in elections is consistent across the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Workers in the seventies were voting in union elections in very high numbers, despite a huge increase in employer resistance. The number of workers voting in union elections dropped significantly in the 1980s and has never returned to the numbers reached in the 1970s.

The decade was also a high-water mark for huge strikes. In 1970, one in six union members went out on strike. This included the massive, illegal strike of 150,000 postal workers, which was the largest wildcat strike in US history. This was the largest strike wave since 1946 and continued on through the end of the decade. Miners struck for 110 days, until President Carter invoked the Taft-Hartley Act to force them back to work. There were huge Teamster strikes and airline strikes. Seventy-five thousand independent truck drivers struck and left vegetables rotting up and down the nation’s highways. For those of us today, this kind of rampant strike activity is almost inconceivable.

The same young people driven by an expanding consciousness of their rights to form unions were also fighting to make their unions more democratic. This was the decade that saw the birth of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and Teamsters for a Democratic Unionand Steelworkers Fight Back, which pushed for greater militancy and racial diversity in the failed presidential bid of Ed Sadlowski. Women unionists founded the Coalition of Labor Union Women, or CLUW, in 1974 to assert their rights as union members and women. CLUW pushed the AFL to support the Equal Rights Amendment and to make child care and maternity leave union goals.

CB: Many labor histories also completely ignore Solidarity Day in 1981, which was the largest rally ever staged by the US labor movement, because it doesn’t fit well with the simplistic picture of labor’s decline in this period.

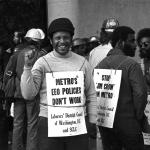

LW: It’s really hard to find information on Solidarity Day. It’s not covered by history textbooks and even by labor history books, which is astounding. Between 250,000 and 400,000 people rallied in the Solidarity Day protest, which makes it larger than or comparable to the 1963 March on Washington. This was in the middle of the PATCO strike, so people were not flying. Instead they rode in on 3,000 chartered buses and a dozen specially chartered Amtrak trains. To make sure everyone could get around, the AFL actually bought out the DC Metro so everyone could ride the trains for free.

When I was researching this I went back to the original sources and looked at the labor newspapers from that time, which were filled with pictures. Looking at photos from the march, it was so clear to me that this group, by 1981, is far more diverse than it would have been just twenty years before. The Civil Rights Act had transformed the workplace, but it also transformed the labor movement.

CB: You also argue that labor scholars like Kim Moody have placed too much of the blame for labor’s fate on the growing labor bureaucracy and have under-emphasized the severity of the employer offensive beginning in this period, is that correct?

LW: I think Kim Moody would agree that the seventies was a decade of growing labor radicalism. In fact, he wrote an essay more or less arguing that in the fabulous book Rebel Rank and File, which included really fantastic essays on strikes, union democracy movements, and public sector organizing. But what the book does not include is anything on private sector union organizing. I think what my research adds to this discussion is an analysis of what the most potent barriers to private sector worker organizing were in this period.

When social benefits are provided as a condition of employment, employers are incentivized to reduce or even completely abandon their obligations by fighting unionization. During the long 1970s, employers came under increasing competitive pressures from globalization. Increased competitive pressures further incentivized employers to reduce labor costs by keeping workers from organizing and to begin demanding concessions from unionized employees. Globalization was also weaponized by employers, who made threats to shut down or offshore plants if employees unionized. So there is a larger economic system that created the conditions for an emboldened employer offensive.

It is definitely true that some unions were too bureaucratic. One reason for this is that unions are charged with administering parts of the employer-based welfare regime while also trying to expand it, and this creates many issues for unions. Nevertheless, I believe that the bulk of the evidence for why unions were not winning labor board elections in this period implicates the employers and structural barriers to organizing rather than the union bureaucracy.

CB: So the rise of global competition and the declining rate of profit led many companies to say, “I can’t control that we are becoming part of a globally integrated capitalist system, but I can control labor costs.”

LW: That is exactly right. From the end of World War II to the mid 1960s, life is good and US business is at its peak and has free global reign. From about 1965 to 1973, things begin to turn. The rate of profit for US businesses falls, especially for manufacturers, who are hit especially hard by global competition and advances in shipping and containerization. Then there are a series of shocks: recession, inflation, the oil crisis. In response, economic power starts to turn away from manufacturing and towards finance. Financiers start treating corporations not as sites of production but as tradable assets.

So one of the ways that businesses react to the declining rate of profit in this period is by targeting labor costs, and especially by getting out from under the weight of their social benefit obligations. Businesses start by breaking down the entire employment relationship and pushing down labor standards. They try to sidestep being on the hook for full-time employees by hiring higher numbers of part-time workers and subcontractors. This is the basis for the rise of contingent workers and what David Weil has come to call “the fissured workplace.”

They also begin fighting union campaigns by firing union activists in exponentially higher numbers and systematically violating the law to thwart organizing drives. Businesses also become more politicized in this period — they organize the Business Roundtable and form many political action committees.

So there are many responses made by the business community to respond to the crisis they are facing. It’s not just attacking unions, but that is a very important part of their strategy for addressing the crisis of declining profits.

CB: According to the data you present in your book, unions won about 80 percent of labor board elections in the 1940s, but that number goes into free-fall in the 1970s and never recovers. What accounts for the precipitous drop?

LW: Employers do three things in the 1970s that make it much, much more difficult for workers to organize unions.

First, they become so much more willing to bend and break the law. Employers began to figure out what exactly you could say to workers to threaten them and get away with it. They also just started routinely breaking the law. The number of Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges, which are filed if an employer breaks federal labor law, doubled in this decade, as did the number of illegal firings.

The way a union election works in this country is that 30 percent of workers have to sign a union card or petition saying they want an election. Most unions don’t file for an election unless at least half of workers have signed a card. Then you file the cards with the government, which organizes an election, which takes ten to twelve weeks. During that time, the employer has free rein to campaign against the union. Managers pull workers into mandatory attendance meetings in which they attack the union, they pull them into one-on-one meetings on the floor. Meanwhile, the union is not allowed on the property. Oftentimes, workers that initially supported the union end up voting against it because the company has scared them so badly. By 1977, workers are winning less than half of the elections that they themselves filed for due to the tremendous impact that employer campaigns have on the organizing drive.

Secondly, even unionized employers at the core of the economy, such as GM, US Steel, and Goodwrench begin to viciously fight worker efforts to unionize. I broke down ULP charges by sector during this period. I expected to see more ULPs in the retail and service sectors because those are the less unionized industries and, therefore, where I assumed employers fought the hardest. I was really surprised because by the 1970s, employees in manufacturing were facing more employer law-breaking than those in the retail or service industries. Companies that were unionized in one place were fighting their workers in other places.

Lastly, employers begin relying heavily on union busters. American universities started teaching practices for resisting unionization in their business schools. Historians may not have known that women and people of color were organizing in the 1970s, but the employers and consultants certainly did. The consultants bred fear about the diversifying workforce to gin up business. One union buster developed a “union vulnerability audit.” How do you determine how vulnerable you are to a union? Well, you count the number of women and people of color in the workplace.

The total effect of the consultants and employers being willing and able to break the law with impunity is that it renders labor law protections for worker organizers meaningless by the end of the decade.

CB: One response to losing elections is to stop running elections.

LW: Exactly. And this bring us to the early 1980s, where the story changes. Half a million workers had been participating in union elections throughout the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, but by the 1980s the numbers plummet. By 1983, only 160,000 workers participate in union elections. The number fluctuates over the years, but never rises above a quarter of a million and never gets anywhere close to the number of workers that were routinely trying to organize in the 1970s.

CB: So the union busting in the 1970s really culminates in the massive declines we see in the 1980s?

LW: Most people mark the era of union busting as having started with Reagan’s decision to fire the striking members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) in 1981, but what my book shows is that PATCO was really the tail end of the last decade of union busting and employer resistance to organizing. By firing PATCO’s 11,000 members and calling in the military to replace them, Reagan normalized the aggressive strike-breaking and union-busting agenda that had already become common in the private sector.

There was the Volcker recession, which crushed union membership in the manufacturing sector. I was stunned by the enormity of union membership loss over a five-year period. For example, both the United Auto Workers and the United Steelworkers lost 40 percent of their membership.

So in this environment, unions begin to pull back from organizing and start running 30 to 50 percent fewer elections. Not just in manufacturing unions that were slammed by the recession, even unions like SEIU (Service Employees International Union) are running fewer elections.

I think that many of these unions just went into a defensive mode and assumed that things would get better after Reagan left office, but they didn’t. Unions never returned to the reliance on labor board elections for growth that we saw in the decades prior to the 1980s.

CB: And the employer offensive launched in the 1970s and sustained through today is also one of the biggest culprits for the dramatic increase in income inequality we have seen over the past four decades.

LW: That is right. According to research from Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld, one-third of the income inequality among men and one-fifth of the income inequality among women can be attributed to the drop in union density since 1973.

That takes into account what is called “the union threat,” which is a name that I really hate, and refers to the fact that employers will take into account the gains in wages and health care made in union contracts and offer them to non-union workers to disincentive unionization. So once unions become weak, it not only hurts workers in that one particular workplace or sector, but in the entire economy, because there is no longer the “threat” of a union to come in and further raise wages and benefits.

CB: So how do we fix this situation?

LW: Well, first, I think we need to all accept that our employer-based social welfare system is fundamentally flawed. And I don’t think you can fix it by just tinkering with existing labor law. Benefits like pensions and health care need to be unhinged from employers, especially now that employers are becoming so successful at unhinging themselves from the employment relationship.

So I don’t want anyone to think that the problem was just Reagan, because then the solution is to simply replace Reagan, which obviously hasn’t worked. What we really need is to build an entirely new social welfare system.

Additionally, this is no time for “fortress unionism,” but for rethinking our understanding of how workers organize. The tools that workers have been given, this weak labor law, is no match for how our employment system is set up and how employers are running their businesses. We have to radically rethink how workers can organize and fight and explore options alongside collective bargaining, not instead of, through which workers can build power.

There are examples. The Fight for $15, the tens of thousands of workers that went on strike for the “Day Without Immigrants,” and the #MeToo movement are all examples of how the labor movement is adapting in the twenty-first century. Collective bargaining–based organizations are part of the movement, but are not the full movement.

So I think it is critically important that we stop accepting a definition of union membership that is defined by the government and the collective bargaining relationship. Fight for $15 activists don’t get counted in government surveys of union members, but they are part of our movement. I think that we need to focus less on the official numbers of union density and focus instead on building worker power.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lane Windham is associate director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor and spent nearly twenty years working in the union movement.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Chris Brooks is an organizer from Tennessee and a graduate of the labor studies program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He currently works as a staff writer at Labor Notes.