Solitary Confinement of Juveniles on the Rise in Cook County

Keon* is 18 years old, with glasses, shoulder-length dreadlocks, and a short goatee. For almost three years he’s been incarcerated in Cook County’s juvenile jail, a boxy white building on Chicago’s Near West Side that houses about 200 teens awaiting trial.

About a year into his time, Keon got into a big fight. As a punishment, jail officials locked him alone in his room for three straight days, he said. He didn’t go to class or get exercise time outside of his cell. He said he spent the days in solitary—also called “room confinement”—reading a book, looking out the window, and rapping to himself.

Keon hasn’t gotten in a fight since, but he said the time he was confined caused him emotional pain.

“You do all that time in your room, you be sick,” Keon said. “It hurt, it hurt the body for real.”

Research shows prolonged solitary confinement can lead to depression, anxiety, and psychosis, and children are particularly vulnerable to these negative reactions because their brains are still developing, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Mental health professionals, advocates, and even many detention center administrators say the practice should be sharply curbed, if not eliminated.

Instead, staff at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center, one of the largest juvenile jails in the country, regularly confine kids for hours at a time, the Reporter has found. Youth in the jail say it’s not uncommon for staff to threaten them with solitary for bad behavior.

Over the past two-and-a-half years, kids at the JTDC have been confined to their cells more than 55,000 times. Taken together, the time they’ve spent in solitary adds up to nearly 25 years.

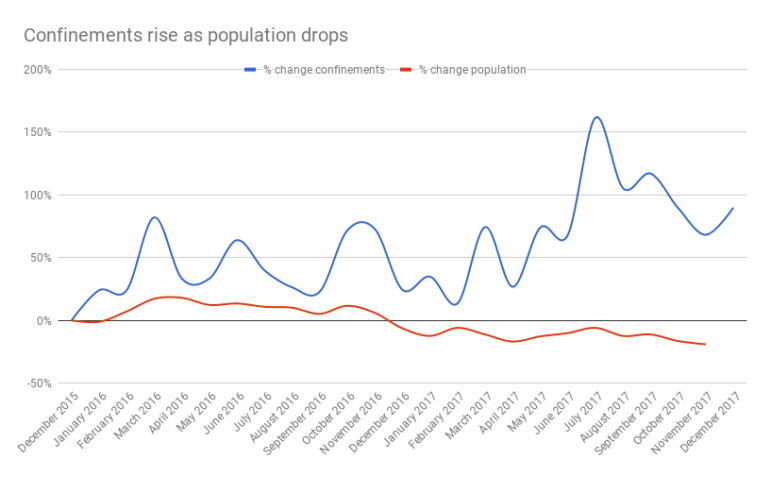

The punitive use of solitary confinement at the JTDC has risen over the past two years, even as the population has shrunk. There were 1,000 more punitive confinements in 2017 than in 2016, an increase of almost 25 percent. The average daily population dropped about 20 percent over the same period.

As the population of the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center dropped nearly 20 percent, the number of punitive room confinements has increased. “Unauthorized movement” is the most common justification for confinement, accounting for 2,392 confinement hours in 2017, a 39 percent increase over the previous year.

Staff at the juvenile jail have confined kids for more than a day for damaging or failing to wear their identification wristband, up to 34 hours for exposing themselves, nearly three days for threatening someone, and up to 10 days for participating in a group fight.

State rules require juvenile detention centers in Illinois to limit room confinement to 36 hours, but they aren’t being enforced. The Reporter found that staff have kept kids in their room for longer than 36 hours in every month since May 2015, when Leonard Dixon took over the facility as superintendent. As recently as December 2017, staff confined two kids for more than 100 hours, while their fellow inmates got to spend extra time with their families for Christmas.

The Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, which inspects county detention centers to make sure they’re compliant with the rules, can’t do anything even if they are non-compliant.

“Other than doing the audit, we have no real authority – no teeth to enforce anything,” said Heidi Mueller, who directs the state agency.

The Reporter focused its analysis on confinements that were imposed as a consequence for violating major rules or getting into fights, because a growing consensus among experts is that juveniles should not be confined as a punishment for bad behavior. National standards from the Annie E. Casey Foundation say that solitary confinement should only be used as a temporary response to youth who are an immediate threat to themselves or others, and that as soon as they calm down, they should be returned to regular programming.

Overall, kids at the JTDC are being confined as punishment for shorter periods of time — the median confinement is about five hours, down from more than 10 hours in summer 2015 — but experts and advocates say even that is far too long.

Dixon, the superintendent, said solitary confinement is a necessary “behavior management tool” — he wouldn’t call it a punishment — and he doesn’t plan to stop using it.

“Confinement is something that you use to ensure that your facility doesn’t get out of control,” he said. “There are consequences for behavior. And we’re not going to run a facility where the kids can do whatever and you have an unsafe place.”

But Mike Dempsey, director of a national organization of juvenile corrections administrators and the former head of Indiana’s juvenile justice agency, said staff who think using confinement makes a juvenile detention center safer are mistaken.

“Kids come out of isolation more aggressive and more dangerous, often, than when they went into isolation,” he said. “You shouldn’t use isolation as a disciplinary tool. Really, no good comes from it. You should avoid it at all costs.”

PHOTO BY JOSÉ ALEJANDRO CÓRCOLES

Three members of the Rapid Response Team walk the halls of the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. The “rovers” or “uncles” as they’re known in the jail, are called when there is a fight or other disturbance, and help confine kids to their rooms.

Chicago behind on wave to end solitary for kids

The suicide of Kalief Browder in June 2015 brought the dangers of solitary confinement for teens into the national spotlight. Browder was arrested in the Bronx when he was 16 for allegedly stealing a backpack, and spent three years incarcerated on Rikers Island while awaiting trial, more than two of them in solitary confinement. Two years after the charges were dropped and he was finally released, he hanged himself. His story was broken in The New Yorker and was widely reported, including in a six-part documentary that was co-produced by the hip-hop artist Jay-Z.

Even before Browder’s death, experts had warned of the negative effects of locking kids and teens in their rooms. A February 2009 study by the U.S. Department of Justice found that about half of juveniles who committed suicide in custody from 1995 to 1999 were in solitary confinement at the time of their deaths.

Although little research has been done on the long-term effects of solitary confinement on young people, mental health experts suggest it can exacerbate existing trauma and mental illness. Roughly one-third of the teens in Cook County’s juvenile jail had a mental health diagnosis on an average day in 2016.

“What we know now is that being exposed to trauma, especially at a young age, changes your body physiologically and changes your brain structure so that you’re more likely to respond more aggressively to certain stimuli,” said Mikah Owen, a pediatrician and assistant professor at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville. “There is a developmentally appropriate way to address kids who are experiencing that, and that is not locking them in a cell.”

The Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators, Dempsey’s organization, which represents the heads of state-level juvenile correctional agencies, has recommended that juvenile facilities reduce solitary confinement. “There is no research showing the benefits of using isolation to manage youths’ behavior,” they noted in a 2015 report.

In 2016, President Barack Obama issued an executive order banning solitary confinement for juveniles in federal custody, but it was largely a symbolic move, since the vast majority of kids are incarcerated in state and local prisons and jails.

That same year, advocates launched the Stop Solitary for Kids campaign, which now has more than 50 supporting organizations, ranging from civil rights groups like the American Civil Liberties Union to the nation’s largest professional associations for correctional employees and administrators. States such as Massachusetts, California, and Colorado, and localities including New York, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., have banned or severely limited solitary confinement for juveniles.

Cook County has gone in the opposite direction. In 2016, a team of juvenile detention experts from the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Children’s Law and Policy evaluated the facility for compliance with the Casey Foundation standards. They found the use of room confinement at the JTDC had increased “very substantially” since an earlier assessment in 2013.

In a strategic plan written in October 2016, the JTDC administration set a modest goal of reducing confinement by 2 percent over the next five years. Instead, the number of confinements has increased. There were 5,536 punitive confinements in 2017, up from 4,453 in 2016.

Illinois is among the states that have sharply limited solitary confinement as a punishment in its youth prisons, as part of an ongoing lawsuit with the ACLU. That leads to the ironic fact that a kid from Chicago can be confined to his cell for hours or days while awaiting trial at the Cook County detention center, when he is presumed innocent, but not once he is found guilty and sentenced to a state youth prison.

Superintendent: Confinement ‘a tool to get kids going’

Leonard Dixon exudes an “I know best” attitude, his confidence matched by his preferred outfit of a dark suit, python-skin boots and a cowboy hat. He comes from a family of law enforcement officers: his father and uncle were among the first black sheriffs in Glades County, Florida, where he grew up.

PHOTO BY JOSÉ ALEJANDRO CÓRCOLES

Superintendent Leonard Dixon said confinement is necessary to enforce discipline and structure on kids at the juvenile jail. “My goal is to reduce confinement as much as I can,” he said. “But I also have to maintain a safe environment for kids. And you can’t do one without the other.”

When he took over the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in May 2015, it was coming out from under federal court oversight. The facility had a history of overcrowding, mismanagement and awful conditions—including excessive use of solitary confinement—which had led the ACLU to file a lawsuit in 1999. Dixon had decades of experience running detention centers in Detroit and Miami. He was heralded by Cook County Chief Judge Timothy Evans, who hired him, as someone with “a compassionate approach” who could get results.

In three interviews with the Reporter, spanning three hours, Dixon professed a tough love approach to the kids at the detention center, in line with the discipline he says he was raised with.

“A lot of times, the reason they’re in here is because they haven’t had any structure,” he said. “As a black male, I am not going to let anybody harm these kids, and I’m going to make sure that these kids get everything they need.”

More than 90 percent of the kids at the juvenile jail are black or Hispanic, and 93 percent of them are male. Dixon noted that kids who are confined to their cells are seen by mental health staff at least once per shift, and that case managers work with them on a plan to improve their behavior.

“We don’t see confinement as just confinement,” he said. “We see it as a tool to get kids going where they need to and to help them.”

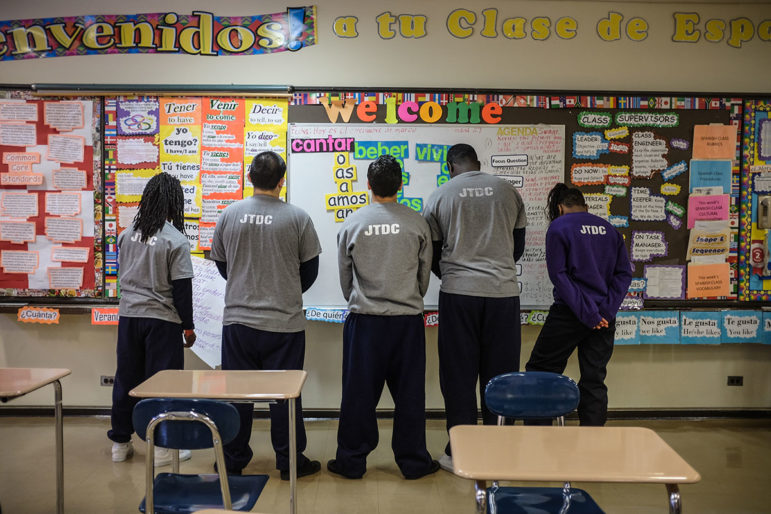

The Reporter interviewed five teens – hand-picked by the administration – in a Spanish classroom at the detention center in late March. Homework assignments and motivational posters covered the walls as the kids sat in a circle in matching JTDC sweat-suits.

Frankie, an 18-year-old from Bridgeport who has been in the JTDC for 31 months, said the youth jail is “all about reprimands,” but it also offers positive reinforcements and gives teens a chance to reflect on what they did wrong and “rehabilitate.” He highlighted the job training programs available to him, like the accredited barber shop where he is learning to cut hair. He almost has the 1,500 practice hours he needs to take his licensing exam.

Staff members “want you to get out and succeed,” Frankie said. “If you’re in here being defiant and just fighting, they gotta do something — they gotta teach you, they can’t just let you do whatever you want and run all over the building.”

PHOTO BY JOSÉ ALEJANDRO CÓRCOLES

Each of the five teens the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center selected for The Chicago Reporter to interview had been put in solitary confinement at some point during their stay there.

But 17-year-old Judy, from North Lawndale, said solitary confinement is the kind of punishment that makes kids want to “give up sometimes on doing good here.” Adam, a 16-year-old from Archer Heights, said solitary can make teens act out more — “bug up” as he put it.

Dixon and his staff pointed to violence by youth in the jail as a reason they need to keep using solitary confinement as a disciplinary tool. They argued that Chicago is different from places that have reduced solitary confinement because the city’s gang violence pours over from the streets into the detention center.

“We have an older population, we have a population with acute mental health issues, and we have a population that comes from a very violent city with gang affiliation, gang issues, and a propensity to violence,” said Zenaida Alonzo, general counsel for the JTDC.

But the team from the Center for Children’s Law and Policy disputed that claim.

“We have no doubt that some youth at the JTDC engage in violent and assaultive behavior,” they wrote in their 2016 evaluation of the JTDC. “But we do not believe that youth in Chicago are fundamentally more violent than youth in state correctional facilities in Ohio, Massachusetts, Indiana, Mississippi, and Oregon, all of which use room confinement for a fraction of the time that it is used in the JTDC.”

The largest category of punitive confinement – and the one that has increased the most since Dixon started – is for “unauthorized movement,” which the Center for Children’s Law and Policy noted could be something as small as stepping outside of the T.V. room. Confinements for fights have remained relatively steady.

“That means what we’re doing is working,” Dixon said. “Because what you don’t do in an institution is allow the little things to get out of control.”

For the detention center to reverse course and begin to eliminate solitary confinement, it seems that change would need to be imposed from the outside, through legislation or legal action.

A spokesman for Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle said in a statement that “we are generally opposed to the use of solitary confinement at the JTDC and would support legislation that significantly tailors its use.”

That could put her in a familiar position: at odds with Chief Judge Timothy Evans, whose office oversees Dixon and the detention center. A spokesman for Evans said he understands there are “differences of opinion” on solitary confinement for juveniles, but “has every confidence in Superintendent Dixon’s expertise and is also mindful and respectful of other viewpoints.”

“Chief Judge Evans will seek further guidance on this matter when the JTDC undergoes an independent review later this year,” he said.

The Center for Children’s Law and Policy has already told the JTDC to cut back on solitary confinement twice. It’s not clear why he expects the third time will be any different.

* The Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center provided only first names to protect juveniles’ identities.

Jonah Newman is a reporter for The Chicago Reporter. Email him at jnewman@chicagoreporter.com and follow him on Twitter @jonahshai.

Want more stories like this?

Get the latest from the Reporter delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to our free email newsletter.